Georgetown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Its Legacies (CSSL), which researches the history of enslavement, celebrated the history of emancipation from enslavement in Washington, D.C. on Emancipation Day April 16.

Emancipation Day is an annual D.C. public holiday to commemorate the signing of the D.C. Compensated Emancipation Act of 1862, which abolished slavery in the District. The CSSL hosted a book talk on the Reconstruction era, a period in U.S. history immediately after the Civil War, and a campus walking tour which highlighted the legacy of enslavement at the university, both on April 14.

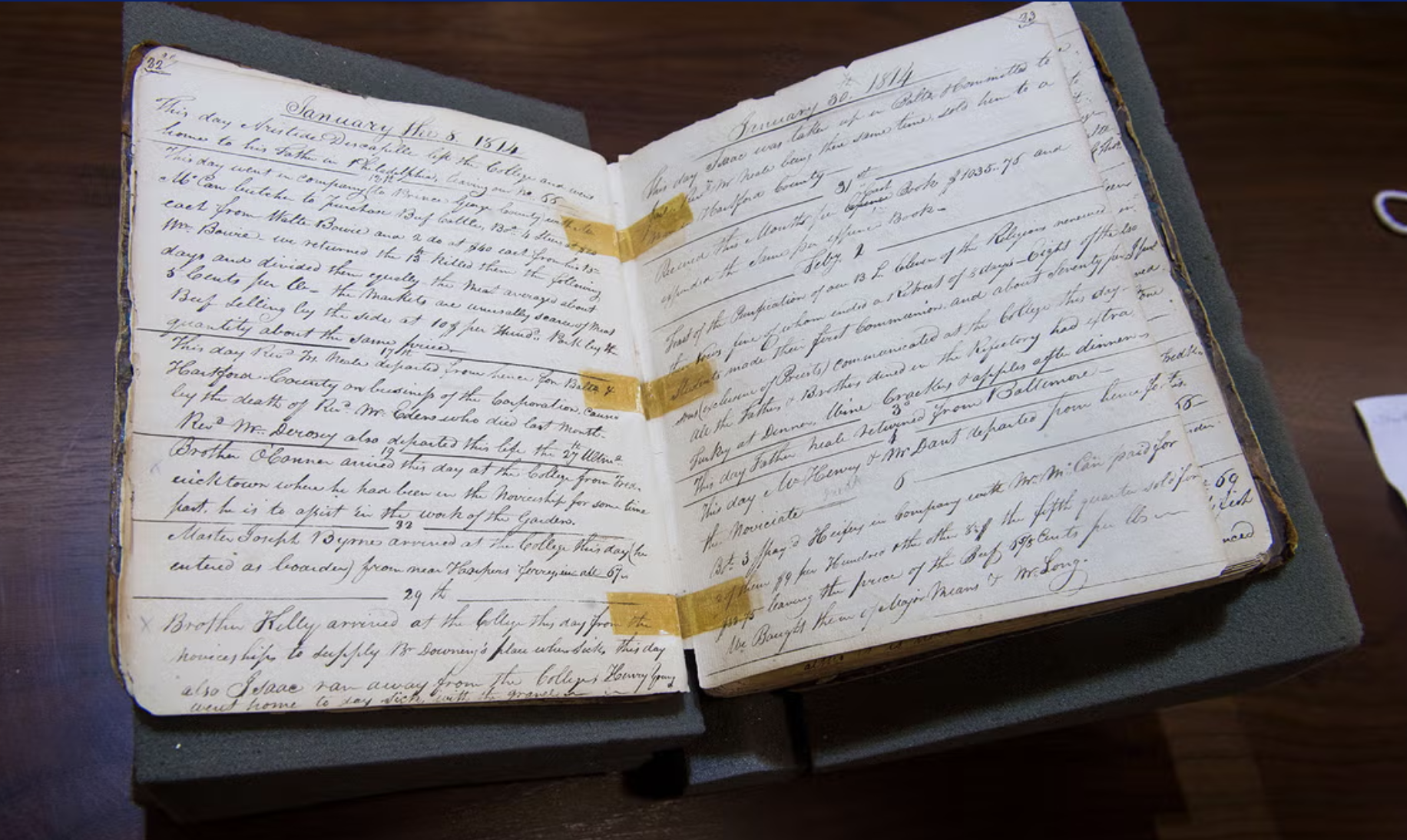

The walking tour included information about campus buildings and sites connected to the university’s ongoing work toward reparations and its commitment to researching the legacy of enslavement at Georgetown. It is based on a 2020 university-sponsored research project that aimed to raise awareness of the Georgetown neighborhood’s historical ties to slavery.

Adam Rothman, CSSL director who led the walking tour, said the tour contextualized Georgetown’s history of enslavement by relating it to specific campus sites.

“I always appreciate the moment on the steps of Old North when we examine the Civil War Centennial Plaque, and people begin to see the connection between Georgetown’s colors — blue and gray — and the warring sides of the Civil War,” Rothman wrote to The Hoya.

Huaping Lu-Adler, a philosophy professor who attended the tour, said the tour encouraged her to think critically about the connection between Georgetown symbols like the Old North Civil War Centennial plaque and the weight that history holds.

“Until that tour, I had no idea that those two colors literally represented the Union and the Confederacy armies, respectively,” Lu-Adler wrote to The Hoya. “The historical evidence of moral equivocation that was recorded in the plaque reminded me of how difficult it can be to have moral clarity and be on the right side of history when you are in the thick of it.”

“It’s easier for us to be morally correct in retrospect,” Lu-Adler added. “That thought, inspired by Prof. Rothman’s explanation of the plaque, is humbling.

Rothman said high attendance at the tour shows the university community is committed to learning about the history of enslavement.

“We had almost fifty people on the tour, including students, faculty, staff, alumni and community members,” Rothman said. “That shows that people want to learn our history on a deeper level, and that a walk around campus is a good way to do that.”

Lu-Adler said the university’s recognition of and reflection on the country’s history drives political progress.

“Remembrance is inevitably political, especially in a country like ours in its present moment, when people occupying the highest positions of power are actively trying to whitewash or selectively erase memories of its past,” Lu-Adler wrote.

“Unless we acknowledge and honestly reckon with our history in all its dimensions, I’m afraid that we won’t be able to make lasting progress in racial justice,” Lu-Adler added.

The CSSL also hosted Kate Masur, a professor of history at Northwestern University and author who has researched Reconstruction-era policies and history in the District, to discuss the legacy of Reconstruction in the District.

Luke Frederick, a Georgetown history professor studying D.C. African-American history, said the persecution and mistreatment of enslaved individuals did not stop just because slavery was outlawed in the District.

“Even after D.C. emancipation was passed and enacted, you still have law-enforcement officers or slave catchers roaming the streets of D.C., still arresting fugitive slaves from other locales,” Frederick said. “So I think it’s important to recognize that D.C. emancipation did not completely eliminate all of the racial barriers, or even completely eliminate these aspects of slavery, from Washington.”

Rothman said it is important to recognize the Emancipation Act’s complexity, as emancipation was an ongoing process with multiple permutations rather than a singular event.

“On one hand, D.C.’s official Emancipation Day celebration helps to remind us that slavery was something that happened right around us and not somewhere else,” Rothman said. “It’s also a gateway to the complexity of history, because it also reminds us that emancipation was a process that was not achieved in an instant or by the stroke of a great man’s pen.”

Frederick said D.C. Emancipation Day is an important recognition of a crucial element of the District’s complex history.

“I think it’s more important than ever to celebrate this holiday,” Frederick said. “Even for its flaws, even though it was compensated and even though there was this sort of colonization element to it, it did improve the lives of thousands of people here in Washington and made it a safe space for people to flock to.”

“I don’t think Washington becomes the city that it is without these emancipatory acts,” Frederick added.