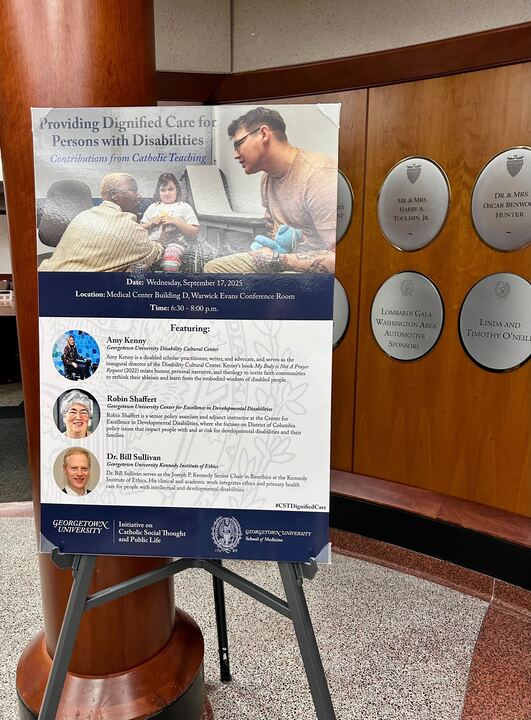

Ruth Noll for The Hoya | Georgetown faculty discussed how Catholic social teachings can inform and improve dignified care for people with disabilities.

Georgetown University faculty members explored the principles of Catholic social teaching and how those principles can shape approaches to dignified care for people with disabilities at a Sept. 17 event.

The Georgetown University Initiative on Catholic Social Thought and Public Life, which aims to promote dialogue on Catholic social thought, hosted the discussion in collaboration with the Georgetown University School of Medicine (GUSOM) student group, Magis, a club where medical students come together to explore the meaning of being a Jesuit medical institution. Discussants examined how Catholic social teaching principles could be combined with political, social and medical efforts to advance quality care for people with disabilities, featuring three speakers who focused on different aspects of shaping care.

Dr. Amy Kenny — a disabled scholar-practitioner, writer, advocate and the inaugural Director of Georgetown University’s Disability Cultural Center — said Jesuit values such as Georgetown’s mission of community in diversity are particularly important in a discussion on disability.

“One of the Jesuit values that matters deeply to the work of the Disability Cultural Center is creating a community in diversity — we know that disability is a part of the biodiversity of humanity,” Kenny said at the event. “Another value that we hold really dear is caring for the whole person. And when we care for the whole person, we care for someone’s access needs.”

Kenny added that, despite the benefits of such care, there is a lack of support for these principles in action in medical care.

“A recent study from Harvard talks about how 80% of us doctors don’t even offer disabled folks the same interventions because they think that we don’t have a good quality of life,” Kenny said.

Robin Shaffert is a Senior Policy Associate at the Georgetown University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities who focuses on policy issues that impact people with and at risk for developmental disabilities. Shaffert said the policy community has only recently begun to acknowledge the disparities in care between disabled and non-disabled people.

“One of the things with medical care is that, because of our system, a lot of people with disabilities do have medical insurance,” Shaffert said at the event. “So that’s a plus, because we always want to talk about positive things, but their outcomes across the board are worse.”

In 2023, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) stated for the first time that people with disabilities would be designated a population experiencing health care disparities.

Dr. William Sullivan, the Joseph P. Kennedy Senior Chair in bioethics at Georgetown’s Kennedy Institute of Ethics, said disabled people are underrepresented in research, leading care providers to lack appropriate knowledge for offering accurate care.

“Those health issues that are more specific to adults with intellectual disabilities only represent about — they represent about 1.5% of the whole population, and so likely they’re not going to get into these general health preventive care recommendations,” Sullivan said at the event. “But there are other types of evidence that typically are excluded, and I would call that evidence from the expertise of people who have lived experience of having a disability.”

Shaffert said that, although there has been a lot of progress towards improving the quality of care, many disabled patients still experience barriers to receiving dignified care, such as ableism or a lack of proper medical equipment.

“People with disabilities will rate their life experience, the quality of their lives, as high, notwithstanding all of these systemic problems that we’ve talked about; but doctors do not see it that way,” Shaffert said.

Shaffert added that another barrier to quality care is that many doctors do not support a disabled person’s agency — when disabled patients go to the doctor’s office with a non-disabled person, the medical professional will often address the non-disabled person rather than the disabled patient.

“That’s the first thing is you have to learn, as a physician to talk to people with disabilities, be comfortable doing that, find out how they communicate, and how you can communicate with them, which is different for each person, that is really a big key to it, and then recognizing that that person is the decision maker,” Shaffert said.

Sullivan said Catholic social teachings can help resolve the lack of agency for disabled patients, noting that the moral element of health care is often excluded from discussions that focus on biological or psychological factors. “There is no space for thinking about the human person in their fullness as moral as well,” Sullivan said. “And so, one of the things that I would say is that Catholic social teaching regarding subsidiarity can be an ethical guide that is deciding healthcare interventions and policies with people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and not for or above or apart from them.”