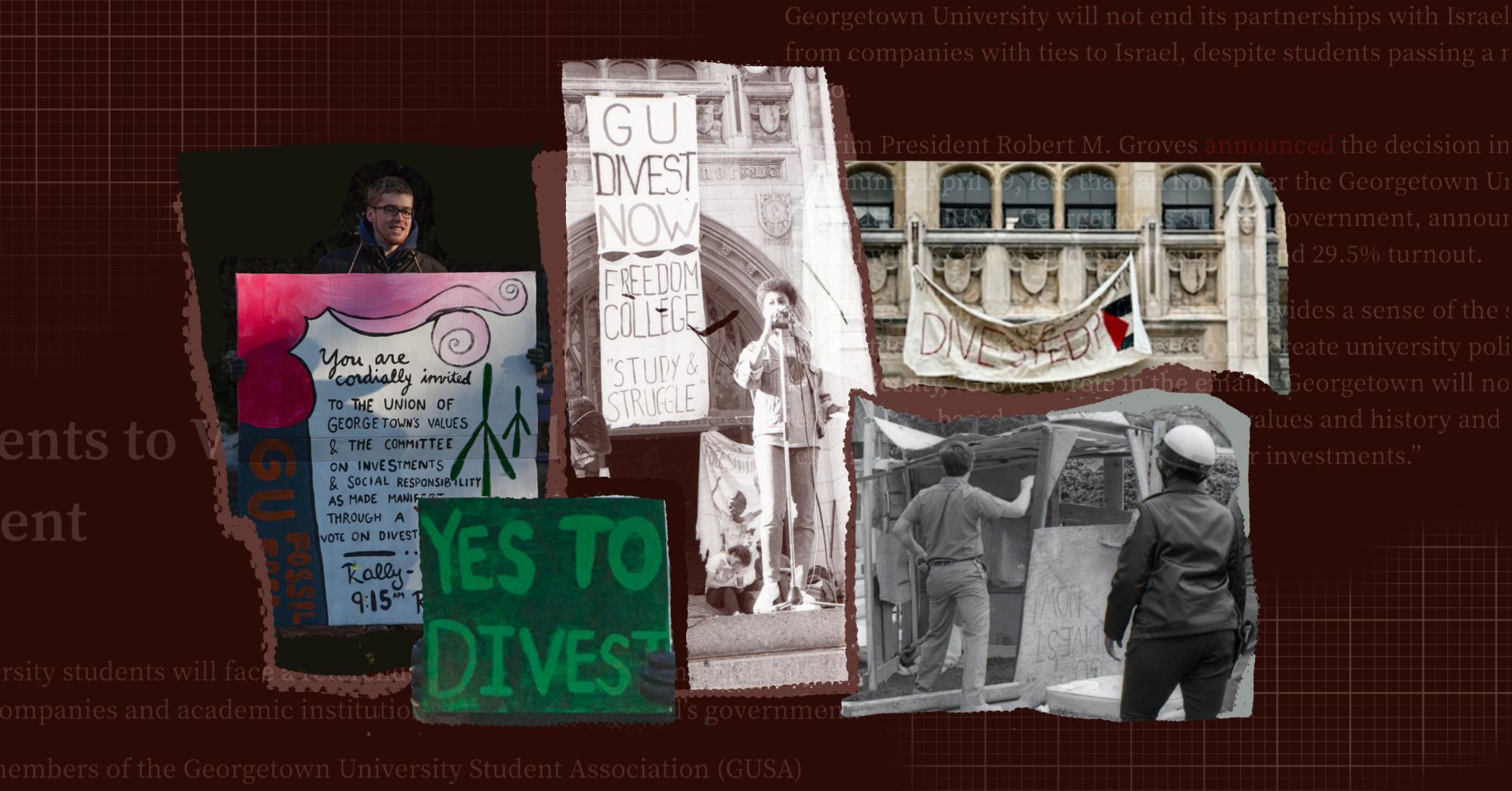

On April 11, 1986, members of the Georgetown University Student Coalition Against Apartheid and Racism (GU SCAR), a student group dedicated to anti-apartheid activism, barricaded themselves in the central entrance to White-Gravenor Hall, setting up a TV and pitching sleeping bags. They called their group the Freedom College, vowing to remain until the university committed to total divestment from South African apartheid.

Fourteen days later, the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) arrested Rumi Matsuyama (CAS ’87) and 34 other students when the group erected encampments on Copley Lawn as part of their protest. MPD handcuffed the students on charges of unlawful entry and loaded them into vans bound for the D.C. Jail.

Matsuyama said the political statement of an arrest was more important to her than any potential consequences.

“We knew what the risks were,” Matsuyama told The Hoya. “It seemed like a small sacrifice to make for an important human rights cause, that I might spend a night in jail and have something on my record.”

Exactly 39 years later, on April 11, 2025, Georgetown University Police Officers (GUPD) forcibly removed student protesters with the Georgetown University Student Coalition Against Repression (GU SCAR), a coalition calling for the protection of pro-Palestinian campus speech, from Healy Hall.

Fiona Naughton (SFS ’26) — a member of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), an organization that endorsed GU SCAR’s protest and advocates for Palestinian liberation and university divestment from Israel — said student protesters today face renewed challenges with university pushback.

“We’re also seeing a period of increased repression, surveillance of students, cracking down on attempts to cover people’s faces, but also visa deportation, the intimidation techniques of the Trump regime,” Naughton told The Hoya. “I think that that has fundamentally altered what advocating for divestment looks like.”

At Georgetown, there is a long tradition of students demanding the university divest from political causes by liquidating its assets in companies that conduct business in certain regions or sectors. In 1997, students called for the university to divest from sweatshops; in 2013, student activism targeted the university’s investments in fossil fuels; and in 2016, the focus was on private prisons. Since 2020, SJP has called for the university to divest from corporations with ties to Israel and its military.

Throughout these eras of student organizing, the university has developed a system to ensure its investment strategy aligns with the administration’s commitment to social justice. Founded in the late 1970s and later expanded in 2012, the Committee on Investments and Social Responsibility (CISR) fields proposals from community members and brings them to the university’s board of directors for further consideration.

A university spokesperson said CISR’s review process is intensive, involving both meetings with the authors of proposals and community input.

“While the length of CISR’s review process varies based on a number of factors unique to each proposal, CISR strives to respond as quickly as possible while at the same time ensuring that each proposal receives a thoughtful and fair review,” the spokesperson wrote to The Hoya.

Theo Montgomery (SFS ’18) — a member of GU Fossil Free (GUFF), a student group that led the charge for fossil fuel divestment — said the key to organizing was knowing how to play the “inside-outside game.”

Montgomery said the “inside game” required negotiating within university institutions, like CISR, while the “outside game” required student pressure and protests.

“We’d show up, sometimes invited to the meetings, sometimes uninvited to the meetings,” Montgomery told The Hoya. “Sometimes we’d rally outside of them and protest with hundreds of people yelling, encouraging them to do something.”

Since 1986, student organizers have played the inside-outside game to push for university divestment. While the tools of campus protest haven’t changed, the rules of the game have.

The Inside Game

Students did not always have a formal arena to play the inside game. Although CISR was founded during earlier anti-apartheid protests, well before GU SCAR formed in the early 1980s, students found interacting with the community challenging.

Marty Ellington (CAS ’84), a founding member and action coordinator for GU SCAR, said that while CISR existed during his tenure, it was inactive and unable to properly respond to student demands.

“The committee went dormant once the previous movement died down,” Ellington told The Hoya. “When we arose, they sort of reemerged.”

Ellington said there was space to appeal to existing university institutions despite these limitations.

“There were individuals in the administration who were sympathetic to our cause,” Ellington said. “While we weren’t explicitly communicating with them, I think that our actions perhaps enabled them to push for more substantive action.”

Over the years, CISR formalized its processes and interacted more frequently with student proposals. The Georgetown Solidarity Committee (GSC), a group founded in 1996 dedicated to advocating for workers’ rights and critically engaged in the sweatshop divestment movement, experienced an ebb and flow in its negotiations with the university and CISR.

Virginia Leavell (COL ’05), a GSC member, said the existence of institutions like CISR offered formal channels for complaints.

“There was a formal process through which to address the fact that there were sweatshop goods in the bookstore,” Leavell told The Hoya.

However, Leavell said she saw CISR’s policies as meant to stall student activists and wait them out until graduation.

“You need to build a campaign that will go longer than four years,” Leavell said. “They literally were waiting for us to graduate, so the campaign would go away. But we would always train and build and empower younger students to be taking leadership roles because you might have to run an extended campaign.”

While the university never formally agreed to divest from sweatshops, GSC experienced individual wins, such as the university suspending its contract with Nike due to unethical labor practices in 2016.

Other organizations negotiated with the university more successfully.

Caroline DeLoach (COL ’16), the founder of GUFF and former undergraduate representative on CISR, said the organization had many constructive interactions with the university and former university president John J. DeGioia (CAS ’79, GRD ’95).

“We got a lot of very positive engagement from President DeGioia’s office,” DeLoach said. “His chief of staff was very willing to meet with us; we had a lot of meetings with him.”

In 2015, GUFF recommended that the university establish a working group on socially responsible investments (SRI) to develop an SRI policy, which the board of directors adopted in 2017. The policy called for “stewardship for the planet and promotion of the common good.”

GUFF used this policy to ultimately advocate for full fossil fuel divestment, with the university board of directors adopting a proposal in 2020 to fully divest from fossil fuels following a student referendum.

Lucy Chatfield (COL ’22), a former GUFF member, said university institutions, like CISR, slowed the tide of change.

“It felt like they didn’t want to deal directly with the student body, so they created this committee so that there would be this theoretical process,” Chatfield told The Hoya.

Like its predecessors, SJP is engaged in negotiations with the university administration. However, according to an SJP media liaison, direct negotiations with the university ceased in 2024 — Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine (FSJP), a faculty organization advocating for Palestinian liberation, has since submitted proposals to CISR.

Juan Ramirez, a third-year doctoral student serving as the graduate student representative to CISR, said CISR heavily engaged with student, staff and faculty calls for divestment, citing the relatively high frequency of CISR meetings in Spring 2025.

“I think we are in a moment of back and forth,” Ramirez told The Hoya. “Last spring CISR, almost in an unprecedented way, took FSJP’s proposal and debated it a lot.”

CISR declined to recommend FSJP’s most recent divestment proposal. However, the committee recommended that the board of directors avoid investments in companies that are directly and significantly involved in gross violations of human rights, as defined by international law.

Ramirez said this proposal exemplified CISR’s slow-moving processes.

“At the moment, the best case scenario is that the board of directors adds a sentence to the SRI policy, and that is frustrating,” Ramirez said. “That’s a recommendation right now, it’s not even changed.”

Naughton — like Chatfield, Leavell and Ellington — said the systems in place are inadequate in addressing student calls for divestment and that, in addition to playing the inside game, student protesters must also play the outside game.

“These mechanisms are fundamentally set up to work within the university’s timeline and resources and their will,” Naughton said. “And I think that if the university doesn’t have a will, then all of these inside mechanisms will be fundamentally ineffective.”

The Outside Game

Thus, when the inside game stalled, student activists turned to more radical organizing to draw attention to their cause.

Marguerite Fletcher (SFS ’86), the GU SCAR president during the Freedom College protests, said regular meetings with the university’s then-president, Timothy S. Healy, did not yield meaningful progress.

“We’d go in with our list of demands, he would listen to us and tell us that it was difficult or say that he would take it up with the trustees,” Fletcher told The Hoya.

At the time, the university was committed to maintaining its investments in companies that followed the Sullivan principles, a set of corporate responsibility guidelines aimed at improving the living and working conditions of Black South Africans while maintaining business operations in the country.

Neil Donahue (CAS ’89), one of the Freedom College protesters arrested in 1986, said GU SCAR members had very little appetite for the Sullivan principles, instead urging the university to divest entirely from companies investing in South Africa.

“Their arguments all required a certain amount of patience — ‘Don’t worry. Wait and you’re going to see that by staying invested in these companies, we will do good. Just give us time,’” Donahue told The Hoya. “I think we realized that they’re under no pressure to do anything.”

To force a university response, students occupied White-Gravenor and erected shanties on Copley Lawn, an escalation that then-Dean of Student Affairs John DeGioia had promised to answer by ending the demonstration. To prepare, GU SCAR retained legal counsel and trained students in civil disobedience in anticipation of arrests.

Donahue said the strategy was intended to draw attention from university stakeholders.

“Bodies in jail were also what got press coverage,” Donahue said. “I don’t remember feeling personally scared. I’ll get taken in, I’ll be released. I didn’t really care about the consequences.”

When the university divested in September of the same year, less than five months after the arrests, they cited recommendations from the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, the Conference of Catholic Bishops of South Africa and CISR, not university protests.

Leavell said GSC’s approach to the outside game was staging large protests that exuded student support for the university’s proclaimed values.

“With the sweatshop stuff, we wanted to be like, ‘We’re better than this. We’re a Jesuit university,’” Leavell said. “At the protests, we did wear blue and gray, we were really pro-Georgetown.”

Samantha Panchèvre (SFS ’19), a GUFF member, said much of GUFF’s momentum relied on its ability to call back to Jesuit values and Pope Francis’s 2015 environmental encyclical.

“They didn’t want to make a statement on Israel, but with climate change, they were like, ‘The Pope believes in it and says we should do something about it,’” Panchèvre said. “They had permission.”

DeLoach said outside student protests and pressure — like a GUFF protest at the Georgetown University Law Center — were central to creating change.

“We made a big show of being there and having sit-ins outside of the board of directors meetings,” DeLoach said. “We were always trying to toe this line between going through it the way that we were supposed to, with the right meetings, with the right stakeholders, while also having very direct ways of showing how much student support there was.”

Although GUFF found success in these tactics, SJP’s efforts have had little impact on university investments.

In April 2025, two-thirds of Georgetown students who voted in a student government referendum endorsed calls for the university to divest from companies associated with Israel. Interim University President Robert M. Groves quickly announced the university would not implement the nonbinding referendum’s calls.

An SJP media liaison said the university has only responded to divestment campaigns aligned with their political objectives.

“It just really goes to show that Georgetown really only will listen to us and listen to our opinions and our voices when it also falls in line with Georgetown’s agenda as a university,” the media liaison told The Hoya. “It really just showed the conditionality of Georgetown values.”

Naughton said a strong outside game was necessary for students pushing for divestment, given the mechanisms like CISR.

“SJP has tried to go through the formal avenues and venues for advocating for this kind of divestment policy, but the university administration has refused to acknowledge the power and legitimacy of those vessels for change,” Naughton said, “which I think must encourage the student body and the Georgetown community to reevaluate whether or not these ways of advocating for change within the system have any power or legitimacy.”

The Fear Factor

Over the last four decades, student organizers have successfully employed the “inside-outside” strategy to influence university investments within various divestment movements. Today, protesters said their approach is different — student protesters face added threats to their physical safety, place in the university community and immigration status.

Since taking office, the administration of President Donald Trump has led a national crackdown against non-citizen residents, particularly targeting students and faculty involved in pro-Palestinian speech with an expanded directive to combat antisemitism on college campuses.

Leavell said universities’ and the government’s crackdowns on campus protests have stifled student activism.

“The way they’re acting now is so anti-democratic,” Leavell said. “Think of the students that are graduating, going into the world having experienced that kind of authoritarian response.”

In March, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security detained Georgetown postdoctoral researcher Badar Khan Suri based on accusations of opposing U.S. foreign policy with his pro-Palestinian speech.

Although Khan Suri has since been released from immigration detention due to First Amendment concerns, his detainment prompted protests for the protection of speech in support of Palestine, including the Healy Hall occupation this past April.

This fear around student organizing was not always so rampant.

Fletcher said Freedom College protesters anticipated university pushback, but never believed their activism would threaten their education.

“It wasn’t like what’s been happening on the campuses this year, that they’re going to suspend you from school or expel you,” Fletcher said. “That didn’t even cross my mind.”

The SJP media liaison said traditional free-speech zones on Georgetown’s campus may be under threat given the university’s new free-speech policies.

“There is a lot more fear that we have now in protesting,” the media liaison said. “Will we be detained if we’re protesting on campus, in Red Square, which was always recognized as a place of free speech? Are we not entitled to that anymore?”

“There is a growing sense of fear,” they added. “However, that fear is definitely not something that’s going to stop people from speaking up. People are going to speak up regardless of how scared they are.”

Georgetown University’s Policy on Speech and Expression designates Red Square as a “public square,” though the university reserves the right to regulate speech based on time, place and manner. However, during his July 15 testimony, Georgetown University Interim President Robert M. Groves announced a partial ban on masks. Under this new policy, students who wear masks while engaging in conduct that violates university policy must remove them at officials’ request.

Naughton said she believes these changes threaten free speech for student protesters on Georgetown’s campus.

“All of the changes to the new code of conduct have been really horrifying in terms of free speech expression. You do have to, in some ways, play a dual response, like a dual role. You have to be both inside and outside,” Naughton said. “But the university isn’t allowing that to happen.”

Ramirez said, despite the changing political landscape, the original strategies of student organizing still apply.

“I am a student of history, and when I look at social movements, the reality is that activists, those pushing for change, have played the inside and outside game,” Ramirez said. “And so if anything, history tells us that successful movements have played both.”

Eugene • Oct 22, 2025 at 9:14 pm

Thank you for this reporting on divestment movements at GU. Just a clarification though, SCAR was Student Coalition against Apartheid and Racism.