As Georgetown University women’s basketball star guard Victoria Rivera (MSB ’26) scored a 4th quarter 3-pointer to lead the Hoyas to a 60-48 win over the Providence Friars on Jan. 18, the crowd of 1,184 people scattered around McDonough Arena applauded around her.

Less than a week later, Georgetown men’s basketball lost 68-78 to Providence — amid an animated crowd of 12,400 fans cheering them on in Capital One Arena.

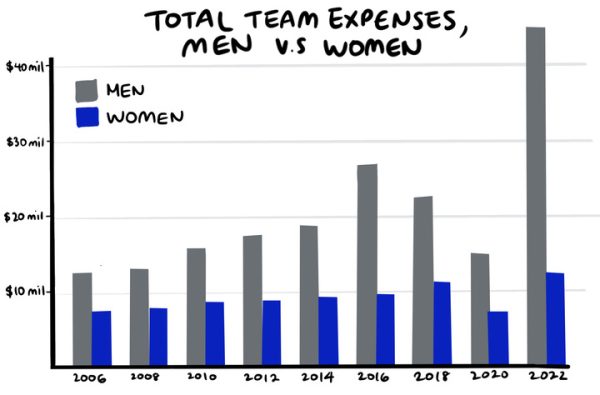

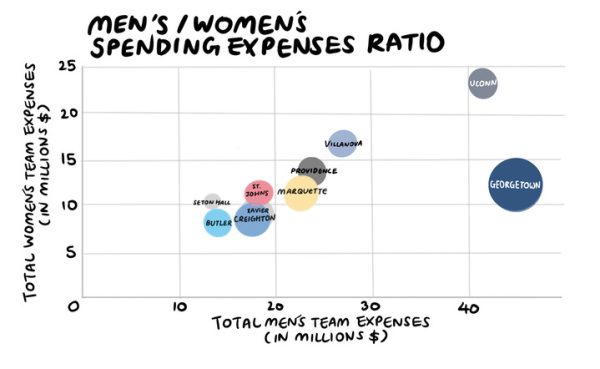

The disparities in attendance between men’s and women’s sports — several women’s games had fewer than 300 in attendance — reflect the imbalance in the university’s investments between men’s and women’s sports. Georgetown spent $44.8 million on its men’s varsity sports programs in fiscal year 2022-23, 366% more than it spent on its women’s teams, which had total expenses of $12.3 million, according to publicly accessible Department of Education data.

The average athletics department generally spends twice as much on men’s teams as women’s teams in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I. The difference is especially pronounced within basketball: Georgetown spends $34.3 million on its men’s basketball team every year, nearly ten times more than on its women’s basketball team, which has annual expenses of $3.5 million.

This unequal resource distribution extends to coaching staff, equipment provisions and recruitment support, among other factors affecting student-athletes. The average annual head coach salary for men’s teams currently sits at $580,565, as opposed to $103,748 for women’s teams. The university also spends more than six times as much on recruiting for men’s teams as women’s teams — $997,498 and $153,634, respectively.

For Abby Kozo (SFS ’27), an outfielder on the softball team, the impacts of differing financial support are tangible.

Kozo said funding gaps make it difficult for female student-athletes to feel a sense of belonging within their athletic departments.

“The discrepancy is just so clear that the women’s teams and the women on the teams can feel that, and I can feel that on a day to day basis,” Kozo told The Hoya. “Being understaffed, being underfunded and having a harder time getting access to these facilities, that then trickles down to almost every other thing that I think women student-athletes experience on the campus.”

Kozo is a member of Voice in Sport, a nationwide advocacy organization focused on advancing gender equity in sports. She testified before Congress last month in support of the Fair Play for Women Act, which aims to improve accountability in educational institutions for gender inequality in athletics.

Athletics funding at Georgetown primarily originates from three sources: the university itself; donors’ endowments; and name, image and likeness (NIL) rights, which have allowed college athletes to make money from commercial activities like product endorsements since June 2021. The existing gap in financial support from the university for men’s and women’s teams widens when taking donor contributions into account. According to Georgetown Athletics, over 75% of sport-specific donations have gone to men’s programs during the past seven academic years, excluding men’s basketball. While NIL as a whole lacks transparency, nationwide data indicates that male athletes have also received far more NIL funding opportunities than their female counterparts.

When asked for comment about the discrepancies, a university spokesperson said Georgetown is committed to equality in athletics.

“Georgetown is committed to providing opportunities for all student-athletes, including our female population, and we are proud of their many accomplishments while competing at the highest level of intercollegiate athletics on the Hilltop,” the spokesperson wrote to The Hoya. “While we are proud of the progress on expanding opportunities for female athletes, we acknowledge that we can and must improve in this area and have prioritized gender equity in our efforts.”

Besides negatively impacting student-athletes’ performance in both the classroom and the athletic field, these funding disparities influence the larger university community, according to Annie Selak, the director of Georgetown’s Women’s Center.

Selak said differences in funding can inadvertently create a campus culture that privileges men’s sports over women’s sports.

“Athletics can impact culture because it is a part of student life, of the campus community at Georgetown,” Selak told The Hoya. “If there’s more effort put into promoting men’s sports versus women’s sports, or if men’s basketball gets to just go by basketball and women’s basketball has to use the adjective women’s basketball, then that subliminally shows that men are worth more energy or effort, or men are the norm and women are secondary.”

“All students at Georgetown deserve equitable experiences, and I think that’s something that shouldn’t be controversial,” Selak added.

History of Title IX at Georgetown

Georgetown’s first female athletes took the field in 1952, when students at the then-all-female School of Nursing established the Women’s Athletic Association to play intramural sports.

Three years later, the university’s first female varsity athlete, Kathleen “Skippy” White (NUR ’57) joined Georgetown’s sailing team, competing against both men and women. In 1957, however, the Eastern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, of which Georgetown was a member, began to enforce rules that excluded White and her female teammates from competitive intercollegiate athletics.

Female student-athletes finally gained legal protection in 1972, when Congress passed Title IX as part of the Education Amendments of 1972, aiming to end sex-based discrimination in education. While Title IX’s scope extends beyond college athletics, the act expanded opportunities for female student-athletes. Title IX requires female and male student-athletes to have equal access to education, material provisions and supporting services, such as medical treatment.

At the time, fewer than 32,000 women competed in intercollegiate sports, on average receiving just 2% of universities’ athletics budgets. Since then, however, the act has spurred increases in female intercollegiate athletics participation. In the most recent academic year, for example, the NCAA reported an all-time high of 235,735 female student-athletes competing across its three divisions.

Naomi Mezey, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center who specializes in the intersection between law and gender, said Title IX radically reshaped public perceptions of female athletes.

“Part of what makes the concept of equality so profound is that it entails adjusting our baseline assumptions,” Mezey told The Hoya. “When Title IX was enacted, our baseline assumption was that men’s sports were important and women’s sports were not important.”

At Georgetown, the passage of Title IX also facilitated massive growth in the university’s athletic budget for women’s teams. The 1972-73 athletics budget allocated a mere $3,400 across six women’s sports, none of which had full-time coaches or scholarships. The most recent reported numbers from 2022-23, however, show the university supports 15 women’s varsity teams and over 300 female student-athletes.

When Title IX first passed, critics complained the law would lead to less funding for men’s sports. Yet Mezey said Title IX gave women crucial opportunities they never had before, thus moving the athletics landscape away from exclusion by gender.

“That’s only unfair if you assume the baseline is that men’s athletics should have all the money; it’s not unfair if your baseline is equality,” Mezey said. “To this day, even though Title IX has radically changed the participation of girls and women in sports, both at the high school and the college level, they’re still not equally funded.”

Critics of Title IX argue that men’s teams should receive more funding because they generate more revenue. Selak said this argument uses fundamentally flawed logic, pointing to the meteoric rise of women’s basketball star Caitlin Clark to mainstream popularity.

“That is essentially rooted in bad economics. Men have received more infrastructure to gain money,” Selak said. “Men have been invested in more, which we see quite literally in the numbers. Now we’re seeing women’s athletics are starting to be minimally invested in, and what’s happening is the numbers are skyrocketing. We see this with Caitlin Clark and the Caitlin Clark effect, both in NCAA and in the WNBA.”

Mezey echoed the sentiment, saying that continuous, generational investment in men’s sports programs, particularly football and basketball, and underinvestment in women’s sports programs perpetuate the current discrepancies.

“The popularity of men’s sports is not a natural state of affairs, it is the product of generations of funding and promotion and scouting and scholarships and recruiting,” Mezey said. “The idea is not that we need to provide extra money to women just on the basis of dignity, we need to provide additional, if not equal, funding for women’s athletics.”

“With equal funding, they can build the women’s athletics program that people want to watch, and women’s sports have proved over and over again that people want to watch them,” Mezey added.

The Gendered Costs of Competition

While Georgetown has taken meaningful strides to improve women’s sports throughout the past 25 years, most recently sponsoring women’s varsity squash for the first time during the 2021-22 season, significant gaps in financial support between men’s and women’s teams persist.

Georgetown’s investment in men’s sports has significantly outpaced its investment in women’s sports, resulting in all-time high funding disparities.

In 2003-04, the earliest year for which the Department of Education has available online data, the university spent $4.47 million on women’s sports and $7.49 million, 1.68 times more than the women’s athletic budget, on men’s sports. By 2022-23, however, the university was spending 3.66 times more on men’s teams than women’s teams, $44.8 million compared to $12.3 million.

The Hoya reached out to multiple female student-athletes requesting interviews. Many cited institutional pressures in rejecting The Hoya’s requests.

A female middle-distance runner from the track and field team, who requested anonymity due to fear of retaliation, said gender biases remain on display in athletics to this day.

“There’s so many discrepancies between men’s and women’s sports as a whole,” she told The Hoya. “If you were to look at any other field that’s not athletics where you’re trying to bring in more equity to the field, it’s ‘yes, you should uplift the marginalized groups.’ That’s very common-sense. But for some reason, in athletics, it’s just not looked at that way.”

Basketball presents the largest funding disparity — the men receive 9.8 times the funding of the women. Yet these disparities are not confined to basketball: In the 2022-23 season, men’s golf received 2.1 times as much funding as the women’s team, men’s tennis received 1.5 times as much as women’s tennis and baseball received 1.4 times as much as softball. In total, funding disparities impact 12 out of 14 of the gender-divided sports teams.

At the individual level, the men’s basketball team received a total allocation of $34.3 million, translating to approximately $2.5 million for each of the 14 players on the roster. Meanwhile, $3.5 million supports the 17 athletes on the women’s basketball roster, just $206,195 per player.

This gender disparity extends to all facets of teams, from their coaching staffs to competition schedules to recruiting capabilities. For head coaches of men’s teams, the average annual salary sits at $580,565, while for head coaches of women’s teams, the average annual salary is $103,748.

While the gap is smaller for assistant coaches — $84,992 for men’s teams and $36,540 for women’s teams — salaries for all women’s teams’ coaches are barely enough to afford the cost of living in Washington, D.C., one of the country’s most expensive places to live, with average cost of living at $50,000 annually.

When it comes to attracting coaching talent, subpar funding for women’s teams makes the task more demanding.

A junior student-athlete who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation explained that insufficient financial resources incentivized the athletics department to cut corners when hiring her team’s next coach.

“When I was asking them how they were looking for coaches, they pretty much said whoever was the closest so they don’t have to worry about helping them with transport or moving in and all those expenses,” the junior told The Hoya. “Online, they’re gonna say they’re doing anything they can and looking for the best coach, but in reality, they were looking for the cheapest option. We had two interviews, and that was it.”

The junior said the hiring process differs for men’s teams, who have more resources at their disposal.

“With any coaching change on a men’s sport, it takes a lot longer, and they have a lot more options than we did,” she added. “As much as we like our coach now — and it was a great change — it just explains what they really cared about, and it was just getting someone to look good, and someone who is cheap, and whoever can start the quickest, rather than who can truly be the best option.”

When coaches do join the staff of women’s teams — especially at the assistant level — they sometimes take on additional jobs to make ends meet, because their salaries from the university are not enough to sustain the costs of living in the D.C. area.

A different junior student-athlete who also requested anonymity said one of her team’s coaches worked a side job for extra income while shouldering the responsibilities of their full-time job at Georgetown.

“I know that one of our old coaches would also do lessons on the side, so it just showed that one job kind of wasn’t enough to support them,” the junior said.

Unequal funding extends to game-day expenses, including equipment costs for uniforms; personnel costs related to coaches, officials and support staff; and travel costs related to accommodations, meals and transportation. Across all teams in 2022-23, game-day spending for women totaled $2.86 million while clocking in at $6.48 million for men.

To work around the limitations of their budgets, some women’s teams had to devise creative solutions when attending competitions.

A student-athlete on the volleyball team, who asked not to be named because of the sensitive nature of the subject, said the student-athletes notice the sacrifices women’s teams must make.

“For one of our away trips, our coaches have had to rent vans to save room in our budget rather than renting a charter bus, which is the norm,” the volleyball player wrote to The Hoya. “On another trip, we planned to take the Metro from the airport back to campus since we didn’t have money to rent a bus.”

“I had to ensure I had time to grocery shop for snacks to bring on travel trips in case there was not enough food available,” she added.

The volleyball player said these discrepancies accumulate, raising the burden female student-athletes bear compared to male student-athletes.

“On a day-to-day basis, I don’t think men’s teams put as much mental energy into working around the barriers that may stem from a lack of funding,” the player wrote. “On a season-to-season basis, I think men’s teams can focus their mental energy on performance and, in general, feel more supported by the athletic department.”

Georgetown’s degree of funding disparity is not normal. In fact, the 366% difference in 2022-2023 was an extreme outlier among schools in the Big East. Creighton, the school with the second-largest gap, allocated only 2.05 times more funding for its men’s teams ($17.4 million) than its women’s teams ($8.53 million), while Xavier’s budget for men’s sports was 2.01 times its women’s sports budget. The other nine schools in the Big East all posted funding discrepancies of less than 2.

That same year, Georgetown’s men’s basketball team underwent a significant personnel change, with Head Coach Patrick Ewing reaching an estimated $11 million buyout to part ways with the university and former Providence College Head Coach Ed Cooley hired to replace him at an estimated salary of $6 million.

Though Georgetown’s disproportionately unequal funding for women’s and men’s sports is not directly attributable to one specific event, the university’s spending on men’s sports is an outlier within the Big East.

Divisions in Donations

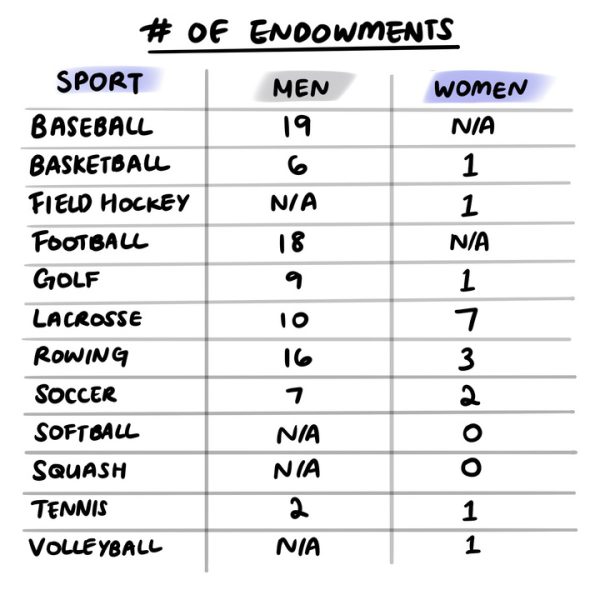

At Georgetown, donor-supported endowments serve three main functions: funding scholarships for student-athletes, hiring and retaining coaches and supporting team needs such as nutrition.

A student-athlete on the women’s tennis team, who requested anonymity due to the sensitive nature of the subject, said she witnessed the differences in funding firsthand.

“A lot of the sports here rely on funding and money from alumni, and that’s where a lot of the differences come from, because I know that my men’s team gets a lot more alumni donations than my team does,” she told The Hoya.

Across all 23 of Georgetown’s varsity sports programs, all but two — softball and squash — have at least one endowment, but while men’s teams have 87 total endowments, women’s teams have only 17 total endowments. The exact amount in each endowment is not publicly available, but endowment funds range from $150,000 to over $3 million, depending on the endowment type.

The baseball team receives at least $2.85 million from its 19 endowments, while the football team’s 18 endowments provide at least $5.25 million. The men’s rowing team’s 16 endowments provide at least $6.1 million.

In contrast, the top three women’s teams in endowment count — women’s lacrosse with seven, women’s rowing with three and women’s soccer with two — received minimums of $1.05 million, $3.3 million and $300,000, respectively. Besides these three teams, no other women’s team has more than one endowment, and the softball and squash programs have zero.

Georgia Ruffolo (CAS ’25), the co-captain of the women’s golf team, said the university has better donor infrastructure in place for men’s teams than women’s teams, causing the disparity.

“I do think it’s getting better, but that’s unfortunately the name of the game right now, and as women athletes, you just have to roll with the punches and do what you can do to compete,” Ruffolo told The Hoya.

A university spokesperson said Georgetown has undertaken various initiatives in recent years to build more financial support for women’s programs, including establishing the Georgetown Athletics Women’s Allegiance in 2022. The program advocates for women’s teams and works to fund more athletic scholarships for women’s tennis, the purchase of two new boats for women’s rowing and the construction of new locker rooms for volleyball and softball.

Kozo said she has immense hope for the future of gender equity in college athletics, but reiterated that Georgetown’s unequal distribution of resources between men’s and women’s teams adversely impacts female student-athletes’ abilities to pursue excellence in all areas.

“It’s tough in college athletics because you want to be focused on school and sport, and perfecting your craft all the time,” Kozo said. “Being given the baseline resources to succeed is as important in the classroom as I believe it is on the field, and I believe it should be for the athletic department and the school as a whole.”

If you have any tips related to gender equity in athletics at Georgetown, please feel free to reach out to [email protected].