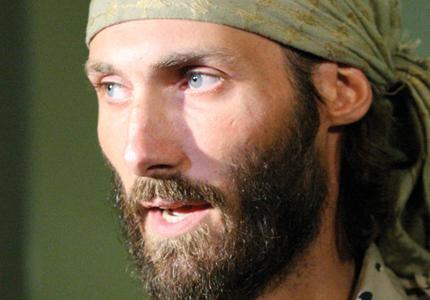

When Matthew VanDyke (GRD ’04) returned to the United States after being detained for six months in a Libyan prison, he was already planning his next trip to the Middle East.

“I’m going to start training … for the next Arab revolution,” he told reporters crowded around him at Baltimore/Washington International Airport when he landed on American soil last November.

In a few weeks, VanDyke will follow through on that promise. This time, he will be heading to Syria, where he hopes to film a documentary about the country’s ongoing civil war.

“Syria’s the next step in the Arab Spring movement, the next regime that needs to go,” he said in an interview with The Hoya. “This is the best way I can help.”

He will be filming alongside Masood Bwisir, a Libyan musician famous for singing rebel songs on the front lines during the Libyan revolt.

VanDyke, who has a master’s degree in security studies from the School of Foreign Service, has had a longstanding interest in the Middle East. According to his mother, Sharon, he begged his family to go on a vacation to Egypt during elementary school.

Between 2007 and 2011, VanDyke rode a motorcycle across the Arab world, working as a freelance journalist during the trip. He visited Syria between 2008 and 2009 and says that he saw signs of civilian dissatisfaction with its government even then.

“[Syria] was one of the countries where I heard rumblings of discontent. I was told a story about the police torturing somebody,” he said.

In February 2011, VanDyke called his mother and told her he was booking a flight to Libya so he could write, film and support his friends fighting the dictatorial rule of Col. Moammar Gadhafi. SharonVanDyke didn’t realize that her son would wind up fighting alongside the rebel forces, dressed in army-surplus fatigues and toting a gun.

“You don’t tell your mother you’re going to fight in a war,” VanDyke said at BWI last November.

On March 13, VanDyke and his companions were ambushed by Gadhafi’s forces while on a mission with the rebel army at the strategic oil port town of Brega, according to VanDyke’s website.

He spent the next six months in solitary confinement in a number of government prisons. He was not physically abused, but he told his mother that the isolation was a form of psychological torture.

Meanwhile, as VanDyke’s mother fervently lobbied for her son’s release, the Gadhafi regime denied having ever detaining him.

On Aug. 24, as rebel forces closed in on the capital, VanDyke’s guards fled, and he was able to escape to Tripoli. However, he was not ready to leave Libya just yet. VanDyke announced that he would not return to the United States until Gadhafi was pushed from power. He remained in the country until early November, manning a mounted Russian machine gun for the rebels.

Sharon VanDyke was not surprised by her son’s decision to remain in Libya after his escape or by his vow to return to the Middle East this fall.

“He was raised that if you start something, you finish it,” she said. “Though when I told him that, I meant not joining the lacrosse team and wanting to quit halfway through the season. I didn’t necessarily mean fighting in someone else’s war.”

Sharon emphasized that her son’s upcoming trip will be very different from his trip in Libya last year, and she does not expect him to engage in armed conflict this time around.

“It’s not the same as Libya, where he had friends and wanted to fight alongside them,” she said. “It’s a very different war.”

Yet the violence in Syria is escalating even as VanDyke enters the final stages of his travel planning. Fighting has reached the Syrian capital of Damascus, where dozens have died from shells and gunfire. On Aug. 20, United Nations observers left the country at the end of a four-month mission that failed to negotiate a ceasefire between the government and the rebel army. Overall, the death toll from the war is thought to exceed 20,000.

The dangers of traveling to Syria hit especially close to home last week, when freelance journalist and Georgetown Law student Austin Tice (SFS ’02, LAW ’13) was declared missing while reporting from the war-torn country.

Tice entered Syria through the Turkish border in May and has provided reporting for several media outlets, including The Washington Post and Al Jazeera English.

According to The Post’s report, Tice was due to leave Syria in mid-August, but his family told the newspaper Thursday that they have not heard from him in over a week.

The Committee to Protect Journalists has called Syria the most dangerous place in the world for journalists, reporting that at least 19 journalists have been killed in the country since November 2011.

Michael Hudson, a professor emeritus in the School of Foreign Service and former director of Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies, elaborated on the scale and intensity of the conflict.

“The uprising has turned into a full-fledged and militarized civil war,” he said. “When you think of the scale of damage and killing that occurred in our own civil war in the 1860s, this is kind of what you’re looking at. It is a very dangerous thing. … It’s not a joke.”

VanDyke said he was not deterred by the dangers.

“There’s plenty of risk involved … but what happens happens. We’re going to be standing there with the men of the [Free Syrian Army], and whatever happens to them happens to us,” he said.

VanDyke’s trips to Libya and Syria have also created a fair share of controversy. CPJ Executive Director Joel Simon wrote in a November 2011 statement that the confusion over VanDyke’s true purpose in Libya endangered other journalists working there.

“VanDyke told his mother that he was going to Libya to be a journalist. So when he was captured … that’s what she told us,” Simon wrote.

The CPJ worked with Sharon VanDyke to raise alarms about her son’s disappearance and to lobby for his return, but Simon later denounced VanDyke for fighting with the rebels while giving the impression that he would be reporting on the conflict.

“Pretending to be a journalist in a war zone is … a reckless and irresponsible act that greatly increases the risk for reporters covering conflict,” he wrote.

The VanDykes countered this condemnation, saying that they had never claimed that Matthew was traveling to Libya as a reporter.

“Some of the agencies I contacted … assumed he was there as a journalist, but we never said that,” Sharon VanDyke said.

Matthew VanDyke also emphasized that although he will not be fighting in Syria, he won’t be reporting from there, either.

“I am not going to Syria to do anything remotely resembling journalism. I do not want any special treatment if I am captured by Assad’s forces. I want the same fate as the men I am captured with,” he wrote on his website.

VanDyke encountered further controversy when his campaign on Kickstarter, an online fundraising tool, was suspended on Aug. 21. Representatives of Kickstarter declined to comment on the reasons for the suspension.

The campaign, which was launched on July 25, had raised more than $15,000 to buy equipment forVanDyke’s project before it was closed. Undeterred, VanDyke moved his project to a similar site calledIndieGoGo.

VanDyke is optimistic about his documentary’s impact.

“It can inspire people to see the cooperation between a Libyan, an American and a Syrian fighter … and that this cause transcends lines that were drawn on a map by men who got here before we did,” he said. “Understand that this is a human struggle. They can view it as an Arab struggle if they want, but it’s really a human struggle.”