When a freshman girl walks onto campus for the first time, she also immediately enters what is known as the “red zone,” the time period in her life when she faces the greatest risk of being sexually assaulted. For freshmen, the first six weeks on the Hilltop are consumed by attempts to fit in with the student body, discovery of the atmosphere of college parties and exposure to what the hookup culture entails.

But the same first weeks are also defined by a dark and hidden reality: a much higher than normal rate of sexual assault.

But according to former Georgetown University Student Association Deputy Chief of Staff Lisa Frank (COL ’13), writing off sexual assault as a problem that only concerns female students who put themselves in vulnerable situations reflects a widespread misconception.

“There’s a lot of slut-shaming, a lot of victim-blaming. I think that people here really buy into the myths that sexual assault is perpetuated by strangers and happens to drunk underclassmen,” Frank, who still serves as a member of the GUSA working group on sexual assault that she convened last year, said. “This is really a whole community problem. It’s not a women’s problem. It’s not a drunk freshmen problem.”

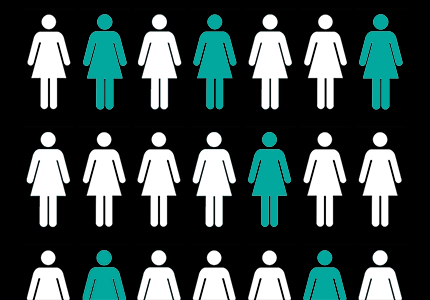

One in four women and one in 33 men will experience sexual assault before they graduate from college, according to statistics provided by the American College Health Survey. While Georgetown’s Health Education Services data concerning sexual assault on campus are not available to the public, Sexual Assault & Health Issues Coordinator Jen Schweer confirmed that the university’s figures are on par with national averages.

Nonetheless, in the campus conversation about relationships, gender roles and campus security, sexual assault is eschewed as a point of discussion.

“The biggest myth is that it doesn’t happen on the Hilltop and that it only happens overseas in places like Darfur and the Congo,” Women’s Center Director Laura Kovach wrote in an email. “Sexual assault does happen on this campus.”

IT HAPPENS HERE

Kat Kelley (NHS ’14) got involved in sexual assault prevention work in her senior year of high school, when she became certified to work for a sexual assault hotline. At Georgetown, she committed herself to the cause on the collegiate level through co-chairing Take Back the Night, co-producing this year’s “Vagina Monologues,” participating in GUSA’s Sexual Assault Working Group and co-founding the student blog “Feminists-at-Large.” As an outspoken leader on this issue, Kelley says that a student who has experienced sexual assault approaches her for guidance at least once a month.

For Kelley, Georgetown’s main problem with sexual assault awareness is that students do not accept that sexual assault, particularly by acquaintances, occurs within the student body.

“There’s just such a silence around it, because unfortunately, there is such a stigma about sexual violence,” she said. “I think that people in theory take it seriously, but I think that a lot of people think that it doesn’t happen here.”

Christian Verghese (COL ’15) founded Georgetown Men of Strength, a group that, during its brief existence, was dedicated to demonstrating that Georgetown suffers culturally from a lack of interest in the subject of sexual assault from the male perspective.

“That underlying mainstream definition of masculinity, I think, is a big root cause for the ways we can overlook and condone sexual violence … in that jocular manner,” Verghese said.

Verghese’s organization focused on determining how its members could empathize with sexual assault survivors and counter destructive definitions of masculinity. It also planned intervention trainings that taught college and high school-aged men how to prevent sexual assault in relationships and at parties where alcohol was present.

“[Sexual assault] is a huge issue not only for women, but for men just to address, because they will probably either be around a situation where it could happen or they might be the person that whether they know it or not is committing the assault themselves,” Verghese said.

Nonetheless, Verghese said that as he transitioned out of his leadership role, membership slowly dwindled and the group ceased to exist. Verghese attributes this lack of interest to the same prevailing cultural definition of masculinity that inspired the group’s creation in the first place.

For Kelley, the problem extends beyond males’ refusal to acknowledge their role in committing sexual assault.

“Males perpetrate it. Males experience it. And males are just as much a part of the community and culture in which it takes place,” Kelley said.

OUTSIDE THE BINARY

LGTBQ Resource Center Director Sivagami Subbaraman sees sexual assault at Georgetown as a consequence of gender roles and, more particularly, generalized conformity to them.

“There’s not much questioning here of gender roles, not much pushing of boundaries, not much challenging. There’s a willingness to fall in line. You come in through the gates and fall in line,” Subbaraman said. “It’s there in the air you breathe and the water you drink, that pressure to conform.”

According to Frank, the culture surrounding sexual assault at Georgetown allows a greater misunderstanding than at other institutions because many students believe that sexual assault is always a man attacking a woman.

While LGBTQ relationship patterns at Georgetown mirror heterosexual ones — from long-term dating to casual hookups and everything between — sexual violence is more often silenced for gay couples.

“I don’t think that most people within the community necessarily recognize that this is also a form of sexual assault or sexual violence,” Subbaraman said.

Subbaraman attributes this silence to the difficulty of interpreting sexual assault outside a mainstream gender binary and Georgetown’s relatively small and close-knit LGBTQ population.

“The naming issue of outing the person who’s doing this to you has far more drastic consequences in the community than I think it would in a heterosexual context,” she said.

According to Subbaraman, LGBTQ students also struggle with an overall acceptance of their relationships by the campus at large, an issue that makes it more difficult to speak out about their problems.

“For gay people in a healthy relationship even, there are very few people I can go talk to when I have an ordinary problem, because my relationship is invisible,” she said. “Our relationships are seen as invisible to people. They are not valued. They are not normal. They’re not seen as therefore having the same validity. That is the real issue.”

While the LGBTQ Resource Center does not have its own resources to address sexual assault, Subbaraman turns students who come to her with cases of sexual violence to the university’s Counseling and Psychiatric Services, and particularly Schweer. According to Subbaraman, sexual assault may go overlooked in the LGBTQ community, but its manifestations are the same as in heterosexual relationships.

“I think the consequences are different, but I don’t think the violence looks any different,” she said.

HOW TO DEAL

Discussions about sexual assault and its prevention generally gravitate toward gender roles, relationship violence and appeals to protect one’s mothers, sisters and female friends. However, Verghese defines his interest in promoting sexual assault awareness through the lens of his Catholic background, which mandates that he recognize every individual’s dignity.

“At the heart of a sexual assault is a man or a woman not recognizing the victim’s dignity,” he said. “When that dignity is ignored, that’s when the … selfish motivations come into play.”

Yet the importance of preventing sexual violence is more than a principle of faith to Verghese, a member of the Knights of Columbus. He said he personally knows students who have been sexually assaulted for whom that experience became a significant part of their Georgetown experiences.

“It’s not only this abstract idea of the glory of God being backtracked. I can tangibly feel the negative effects of sexual assault on campus,” he said.

Based on this perspective, Verghese believes that sexual assault awareness and prevention are most effectively executed on an intimate, person-to-person level.

In line with that thinking, Georgetown created the position of sexual assault and health issues coordinator, housed in Health Education Services, in 1999. The position is designed to provide a direct response to survivors and the promotion of personal education and outreach. Today, Schweer, the coordinator, meets with those who have been assaulted to offer advice on seeking justice through on-campus and legal channels. She also follows up on medical care, offers assistance related to housing and academic concerns and counsels the friends and significant others of survivors.

However, Schweer also works on the institutional level to promote awareness education, training and policy work regarding sexual assault on campus, in collaboration with HES, CAPS, the university’s Sexual Assault Working Group and the Women’s Center, which was founded in 1990 in order to address specifically sexual assault and harassment on campus.

In recent years, these partnerships, especially the working group, have made significant impacts. It has effected a more redefinition of sexual assault in the Code of Student Conduct that uses the term “survivor” as opposed to “victim.” It also led the initiative to bring the sexual assault and relationship violence liaison position to the Law Center and ensured that Georgetown complies with federal regulations on sexual assault.

Along with these initiatives, the university has institutionalized RU Ready and its related sexual assault peer educators, which train students that work with on-campus organizations and residence hall floors on how to hold discussions about sexual assault prevention.

But for all of this progress, there is debate over how effective these programs are in the immediate term, mainly because they are largelly geared toward those who are already familiar with sexual assault resources on campus.

“The people inviting those groups in are not the people that need to hear it,” Frank said.

In order to further address the problem of sexual assault at Georgetown on a wider scale, former GUSA President Clara Gustafson (SFS ’13) and Vice President Vail Kohnert-Yount (SFS ’13) created their own Sexual Assault Working Group in November 2012.

Separate from the working group that exists under the official purview of the university and that meets once or twice a year, this version is composed entirely of students who meet every one or two weeks to brainstorm how the university can better prevent sexual assault on campus and raise awareness of the resources available to survivors.

“Our goal would be not to eliminate sexual assault, because I don’t think that’s possible, but to get to the point that everyone that’s part of our Georgetown community understands all of the different dynamics that play into it, and that everyone is capable being a supporter, everyone is capable of not stereotyping, not victim-blaming, not using words that are hurtful and perpetuate these problems,” Frank said.

One major project currently under development is the incorporation of a discussion-based sexual assault education program in New Student Orientation, which would be led by specially trained student facilitators. The goal, Frank says, would largely be to eliminate a dominant culture that jokes about sexual assault all too carelessly.

“People learn from day one that it’s OK to make jokes about rape, that it’s OK to sexually coerce people — particularly freshman women — and there’s also a lot of pressure to be sexually active and to partake in drinking and other behaviors,” Frank said. “I think that there are a lot of really awful things that get said and that people believe, and there’s no one … checking that right now.”

Kelley agreed that the attitude toward sexual assault, as reflected in everyday language, is problematic.

“No one in the history of the world has taken the word fondling seriously,” she said. “That is so invalidating of what happened to the survivor.”

The working group also supports efforts to create an amnesty policy such as the one included on the campaign platform of GUSA President Nate Tisa (SFS ’14) and Vice President Adam Ramadan (SFS ’14), who were sworn in last weekend. Measures of this kind would guarantee that students who report cases of sexual assault would not be punished for other disciplinary offenses, like alcohol policy violations, that occurred at the same time as their assault.

While many of the ideas being tossed around by the GUSA working group are still in their preliminary phases, Frank believes that this discussion is a strong first step for Georgetown.

However, the ultimate goal of these initiatives is to decrease rates of sexual violence on campus, and there is hope that programs like the one proposed for NSO can be institutionalized and create measurable change.

For that to happen, Subbaraman says Georgetown needs systemic changes, like more resources in Health Education Services, and more personal engagement.

“At the end of the day, this isn’t about providing brochures and buttons,” she said. “It’s one by one by one. It’s time-consuming and energy-consuming.”

If you or anyone you know has experienced sexual assault and is looking for assistance, please contact Jen Schweer, [email protected], or the DC Rape Crisis Center Hotline at 202-333-RAPE. Health Education Services also provides resources for those who have experienced sexual assault at be.georgetown.edu.