Writers and artists advocated for literature strengthening the environmental movement during a Georgetown University symposium March 25 to 27.

The Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice, which fosters campus engagement with contemporary literature, hosted the event, titled “Writing Climate,” which featured expert panels, student artwork and readings. The symposium, co-hosted with Georgetown’s Earth Commons, an institute studying sustainability, invited attendees to reconsider their relationship with the environment and explore literature’s role in climate action.

Rabih Alameddine, Lannan visiting chair, said the symposium focused on solutions to climate change to give writers and attendees a direction for activism.

“It’s an existential threat, and I’m interested in how, as writers, how do we deal with this,” Alameddine told The Hoya. “For the most part, we seem to know about it, but we don’t know what to do about it.”

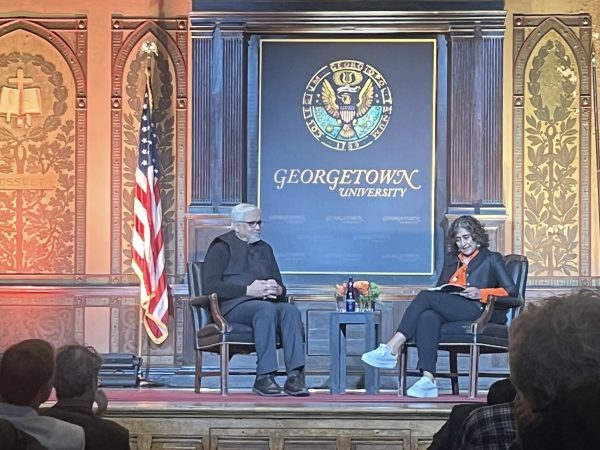

The first day of the symposium included a performance by an environmental dance company, followed by a keynote discussion with Amitav Ghosh, an Indian writer specializing in colonialism and climate change.

Ghosh said writers face systematic barriers to publishing environmental-centered work, noting publishers do not match writers’ interest.

“Many writers have been engaging on these subjects, writing on these subjects,” Ghosh said during the event. “I think the greater problem lies in the broader ecosystem of literature. Even when the writer produces this work, does it find a place in the major reviews, does it even find a publisher? That’s where the real problem lies.”

Ghosh said environmental literature should reflect the broader issues facing the environment, not just climate change.

“It’s not just about climate change; it’s everything change,” Ghosh said. “What we have really is a whole set of interlocking crises — biodiversity loss, species extinctions, new pathogens and all of these are simultaneously manifesting themselves in the body politic.”

“That only makes the subject even bigger and even more challenging,” Ghosh added.

Livia Sun (GRD ’25), a master’s student in the environment and sustainability management program who attended the event, said the symposium humanized climate change.

“When you think of climate change, a lot of times the topic is spoken about in a really technical way,” Sun told The Hoya. “I think that’s why I really enjoyed the first performance, because it was less technical.”

The symposium’s second day featured two indigenous writers, dg nanouk okpik and Linnea Axelsson, who spoke about land use and indigenous rights; a student environmental art showcase; and an interview with Kumi Naidoo, a South African human rights and environmental justice activist.

Alameddine said the symposium responded to President Donald Trump’s administration, which rolled back climate regulations and restricted use of the term “climate change.”

“It’s important today because we have an insane administration that is already cutting any kind of miniscule achievements that we have made in terms of dealing with the crisis,” Alameddine said. “It becomes a topic of extreme importance.”

Sun said the symposium improved access to information about climate change as the federal government deprioritizes it.

“This theme hits really hard right now, particularly because we’re in D.C.,” Sun said. “There’s a lot of changes going on in policy and administration, and I think for the most part, a majority of people believe that the climate is changing. Just trying to make that information broader and more accessible juxtaposes everything that’s happening in the political and technical world.”

The third day included a reading from the environmental novel “Silent Spring,” which jumpstarted the modern environmental movement, and discussions with an environmental biologist and two writers about communicating about climate change.

Alameddine said he hopes to highlight individual solutions to climate change, encouraging attendees to take action regardless of the scale.

“Obviously, we have to follow the news, we have to follow the things that are happening, but in this time it’s more important than ever to focus on the things that communities and people are doing to feel good,” Alameddine said. “Even if you do it and it’s a small thing, it’s good to work to do as much as you can — even if it’s weeding. The motto is, if you can’t be here, weed.”