The first report of a H5N1 infection in a pig on a backyard farm in Oregon was confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Oct. 30.

H5N1, commonly known as avian flu, is an influenza virus which has spread quickly among poultry, cattle and several other mammals across the United States. The CDC reported there have been 44 human infections since April 2024, all associated with exposure to infected animals except one, whose source could not be determined.

The animals on the Oregon farm were not intended for commercial food supply, so there is no concern about a threat to the nation’s pork supply, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

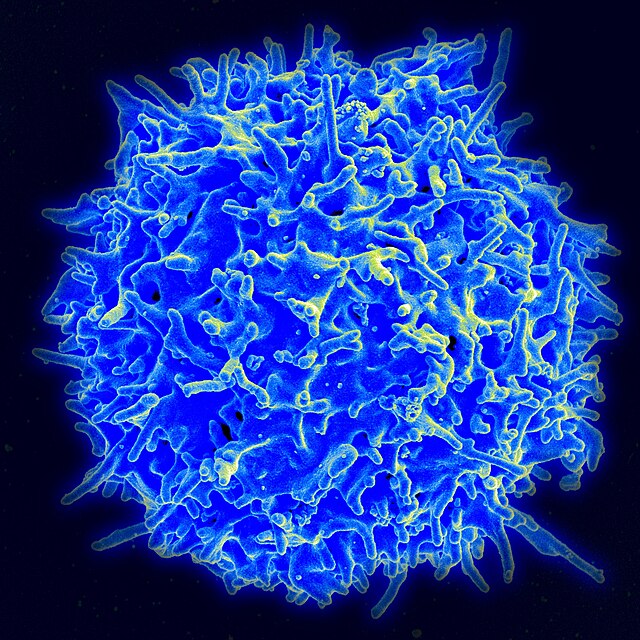

However, the discovery of H5N1 in pigs is particularly concerning, as pigs have a reputation as “mixing vessels” for influenza viruses. Lawrence Gostin, distinguished professor at Georgetown University Law Center and director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center on National and Global Health Law, said that when two viruses infect the same host, they can exchange genes in a process known as genetic reassortment. Both animal and human viruses can infect pigs, so an animal virus could exchange genes with a human virus in the pig and potentially gain the ability to infect people.

“The most concerning thing is that pigs can harbor both human and animal viruses and they can swap genes and potentially become more dangerous,” Gostin wrote to The Hoya. “The last thing we need is an avian influenza that is more contagious human-to-human and highly pathogenic.”

The CDC reports that the H5N1 virus that infected the pig did not undergo changes that increased its ability to infect humans. However, Dr. Jesse Goodman, professor at the Georgetown School of Medicine and director of the Center on Medical Product Access, Safety and Stewardship (COMPASS), was concerned about H5N1 even before this development because of how adept it has become at infecting different species of mammals.

“I think that this outbreak right now, even before this, was quite unprecedented in its scope, in the number of mammals already involved,” Goodman told The Hoya. “We never before saw widespread infection of mammals, which we are seeing with marine mammals and cows.”

Monitoring the spread of H5N1 is vital to ensuring it does not become a widespread threat. However, surveillance has proved challenging. Rebecca Katz, a professor at the School of Medicine and School of Foreign Service and director of the Center for Global Health Sciences and Security, said varied approaches by each state complicates the surveillance of H5N1.

“Different states are approaching surveillance in different ways,” Katz told The Hoya. “There are some entities that are looking heavily at wastewater surveillance, there are some doing aggressive testing in farmworkers, there are some who are doing none of the above.”

Further complicating matters, Katz said pandemic preparedness is hindered by a pattern of panic during health emergencies and neglect afterward. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has entered the “neglect” phase, according to Katz.

“In our field, we have something called the cycle of panic and neglect where the more people panic during an event, the more they neglect the space afterwards, and we’re pretty deep into the neglect cycle,” Katz said.

Goodman said a lack of trust in vaccines and public health in recent years also contributes to challenges in the H5N1 response.

“Vaccines got politicized. We’re seeing that down to the wire in this election,” Goodman said. “So I think that’s another area where we have a huge amount of homework to do to restore trust in vaccines and restore trust in public health. Part of the reason CDC and state health departments have been unable to stamp out this outbreak is that states and private industry often don’t want and don’t trust public health on their farms.”

Goodman also stated the importance of receiving seasonal influenza vaccines, but emphasized that it is impossible to know how effective they will be against ever-adapting influenza viruses.

“In a very good year they might reduce infection and hospitalization significantly, like 50-70% in healthy young people, but in older people or when they are not as well matched, the vaccines may have significantly lower efficacy,” Goodman said.

While the H5N1 virus has pandemic potential, experts say the overall risk remains low and can be mitigated with appropriate measures.

“Overall, we should be vigilant but not alarmist. The risk is still relatively low and can be contained with smart public health policies,” Gostin said.

Goodman emphasized the importance of collaboration between farmers, public health officials and the government to ensure that H5N1 does not become a global threat.

“It’s not a matter of being for or against public health or for or against vaccines. But all of us may be against having a pandemic that really hurts both agriculture and people throughout the world,” Goodman said.