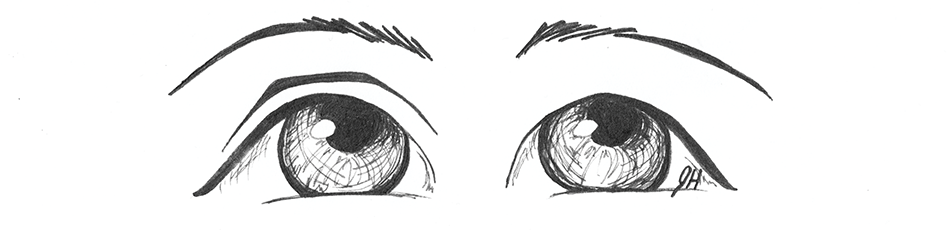

“Are you half? You have big eyes, for an Asian.”

“You have bigger eyes than some of my white friends!”

“Have you gotten double-eyelid surgery? Your eyes are pretty.”

“You have really western features, for a Korean.”

These are a few of the many common statements I have been asked or told in my lifetime as a Korean woman living in America. From a secluded New Jersey village, a small town in the middle of Long Island and an even smaller one on the North Fork, where the largest buildings were a school and the CVS, to the vibrant East Village of New York City, I found the size of my eyes to be a frequent topic of discussion with friends, classmates and even strangers at a bar.

They are comments that seem to call for an automatic, responsive “Thank you.” However, as I have developed my identity as a Korean-American throughout the years, I have realized the weight that the historical relationship between imperialized South Korea and the powerhouse United States has had in these complex statements, laden with indirect and subliminal reassertions of “white superiority.”

It is no secret that South Korea has been spearheading the global cosmetic surgery market. Korean women undergo the most surgical procedures at the highest rates per capita; in a 2012 report, The Economist listed South Korea as the country engaging in the most plastic surgery. What may not be obvious is that the commentary on the amount and manner in which Korean women participate in plastic surgery is in direct conversation with the history between the United States and South Korea.

Centuries ago, attempts to open the secluded Hermit Kingdom to global trade were met with slammed doors and sometimes violence. From the British East India Company’s ship Lord Amherst in 1832, Catholic missionaries, the U.S. General William Tecumseh Sherman in 1866, to the “Little War with the Heathen” that erupted from Korean resistance, forces pushed fiercely against South Korea and the Korean peninsula finally became prey to globalization and Western imperialism.

The positive aid that America provided during the volatile and capricious time of the Korean War is indisputable — had there been none, South Korea might not exist as we know it today. But America’s presence after the civil war in Korea is highly controversial. U.S. intervention continued for as long as it did to capitalize on economic resources, strategically draw from Korea’s location and further its global hegemony.

After the ceasefire began, no other country was allowed to have as much weight in post-war Korean affairs as the United States and it therefore secured a sense of superiority throughout the peninsula. The ideals of masculine, white America in the mid-19th century became a symbol of modernity, cleanliness and vast opulence to which Korea was unfamiliar. As Koreans were continually confronted with the Western ideal and American dream, their subsidiary status became solidified in the contention between a “has” country and their “has not” home.

In a rapid push for modernization, Korea lifted itself out of poverty, found economic footing and began to take part in the typical Western bourgeois lifestyle, leading to a waver and wane of America’s feeling of superiority and dominance. Korea’s technological advancement, exemplified in its leading cosmetic surgery market, aggravated America’s status-quo level of supremacy. Many American media outlets began criticizing Koreans as engaging in “perverted excess” to look “more American” and “westernize” their Asian facial features.

Koreans who underwent double-eyelid surgery to make their eyes much larger, nose surgeries to give themselves higher noses and jaw reconstructions to make their faces more slim and narrow were all described as shedding their Korean appearance in favor of a more “westernized look.” It is irrefutable that the amount of cosmetic surgery some Korean women undergo is alarming and extreme, but it is glaringly incorrect to liken the reason they do to a desire to look American.

Larger eyes and smaller noses have traditionally been considered beautiful features in Korean culture and have never belonged exclusively to the West. If we assume the imitation of race, would it then be appropriate to say that white women tan as a function of their deep desire to be Hispanic? The act of America placing its beauty ideal as the standard, global measuring stick comes from its familiarity in being the greater power in relation to South Korea. The historical relationship has so effectively permeated generations that many are not even aware of the implications of these statements.

The strides Koreans have taken to differentiate and advance themselves from historical subordination are met with subconscious deprecating racialism, no longer as direct, scathing and outspoken as calling Koreans “gooks” and “zipperheads,” but in the statements of, “they do this to be more like us.”

Sarah Kim is a junior in the College.