My favorite childhood movie “The Lion King” provides the perfect analogy for my Jewish identity. In the film’s turning point, Rafiki tracks down and confronts Simba, who lives in exile after his father Mufasa’s calamitous death. Rafiki wants Simba to go home to the Pride Lands and rectify its current suffering, while Simba wants to continue living by “Hakuna matata,” or “no worries.” A metaphysical debate ensues.

Simba argues the past is unchangeable and thus inconsequential, but Rafiki counters that Simba is merely afraid to face it. Obviously, Simba cannot bring Mufasa back to life, but what he can do is bring peace and prosperity back to the Pride Lands. When Simba takes his rightful place as king, he improves conditions in the kingdom, but he also alters the nature and significance of Mufasa’s death from a senseless tragedy to a chapter in a longer story of redemption.

Embedded in Rafiki and Simba’s dialogue is my answer to the essential question: “Why do you choose to live Jewishly?”

Dedicating myself to promoting Jewish values and the welfare of the Jewish people, I live Jewishly to honor the Jewish past. Like Simba, I have a role to play in the framing of the past. It is common knowledge that Jewish history is rife with trauma, most notably the Holocaust. While I cannot undo the persecution we have faced, I can imbue it with significance through my own life.

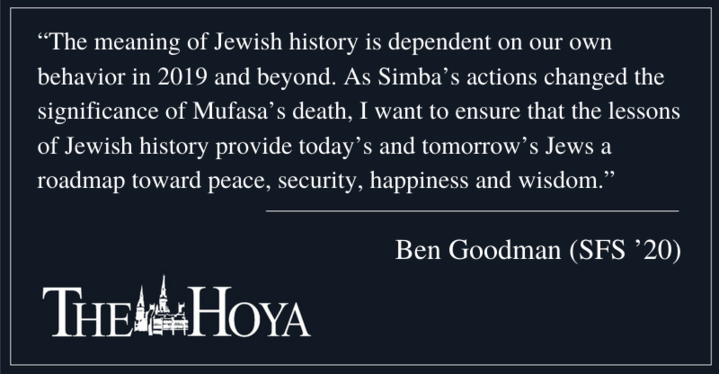

The meaning of Jewish history is dependent on our own behavior in 2019 and beyond. As Simba’s actions changed the significance of Mufasa’s death, I want to ensure that the lessons of Jewish history provide today’s and tomorrow’s Jews a roadmap toward peace, security, happiness and wisdom.

For an American example of redefining the past, we cite the Declaration of Independence as a beacon of natural rights. However, it took abolitionists, suffragists and Civil Rights marchers centuries to harmonize our practice with our self-image. The declaration was written in 1776, but its message lands differently today than it did in the 1950s because of the achievements of people much later. New moments reframed those of the past.

Jews respond to the call to live Jewishly in a wide variety of ways. Some engage in social justice activism, some dive into Torah study, some advocate for Israel and Jews worldwide, some cultivate a Jewish family and still others strive for personal success to vindicate their predecessors’ lack of opportunities. For many, myself included, it is all of the above.

I see the meaning of the Jewish past changing every day. When Virginia elects its first Jewish female house speaker, I think about the previous Jewish generations worldwide shut out of the political process. When Israelis persevere through conflict, I remember that their grandparents relied on the fickle mercy of others to keep them safe, and I rejoice in the Jewish people’s national liberation.

When I teach Hebrew school at Glover Park’s Temple Micah, laughing at my sixth graders’ wisecracks and marveling at their kindness and intelligence, I wish that the martyred Jews of history could see us. I hope they would have felt reassured that, while they were history’s victims, the lessons of their suffering have solidified our will to survive and pass on the traditions of our people, l’dor vador, from generation to generation.

I see the darkness of the past around me, too: rhetoric ostracizing Jews and other minorities, blaming complex problems on easy scapegoats, cruelty, self-centeredness and cowardice at the cost of needy people. Yesterday’s grim echo implores us to act courageously against fear-, hatred- and grievance-based politics.

Every day, I wear a chai necklace. Chai, or “living,” serves as a prominent symbol in Jewish tradition. It reminds me that, against all odds, I am here — alive — the latest of an ancient people that somehow keeps sticking around. The Jewish story is a living story, an invisible thread that links my family and me to the generations that came before us; past and present are connected.

Picture yourself with a partner, literally tethered together by that thread. When you walk forward, you bring your partner along with you. The future of today’s global Jewish community will change the meaning of the triumphs and tragedies of its previous iterations. The past lives on through us.

Ben Goodman is a senior in the School of Foreign Service. Interfaith Insights appears online every other Wednesday.

Nicole Prozan • Jan 6, 2020 at 6:24 pm

Aspiring Georgetown student here (also Jewish). This piece is wonderful and thank you so much for sharing!

LF • Nov 24, 2019 at 1:30 pm

Kol Hakavod! Beautiful and inspiring sentiments.