Regardless of whether Georgetown University’s incoming first-years are studying hard science or humanities, all are united by a common obligation to the university’s core curriculum — in particular, the two theology courses every student must choose between.

“Intro to Biblical Literature” and “The Problem of God” — the latter of which students opted for at a rate of roughly nine-to-one this semester, according to the theology and religious studies department — are two of the most well-known courses on the Hilltop.

“The Problem of God” is an age-old course at Georgetown first taught in 1967, its name inspired by a series of 1962 lectures that John Courtney Murray, a Jesuit professor, gave at Yale University.

This semester, 33 sections of “The Problem of God” are being taught by more than 20 different professors, and without a standardized curriculum, every student across these courses will have a distinct experience compared to that of their peers.

Kerry Danner, a professor in the theology and religious studies department who specializes in Christian ethics, said that she includes big-picture theological components in her syllabus, like various approaches to the question of suffering, in hopes it will leave a lasting impact on students.

“If students are invited into a way of thinking about the bigger questions in life now, hopefully they will keep that,” Danner said in an interview with The Hoya.

“I really try to frame it as Georgetown’s invitation to students to go deeper into their sources of meaning in their life and their sources of solace,” Danner added.

The scale of “The Problem of God” remains unparalleled among Georgetown classes, with over 100,000 students having taken a section of the course over roughly 50 years.

With so many different options to choose from, Min-Ah Cho, a professor in the theology and religious studies department, said to get the most out of the course, students should approach their section with an interest in expanding and challenging their existing perspectives.

“Be open-minded when you take ‘The Problem of God.’ When you open your mind and try to listen to your professors and your peers, you will actually get a lot,” Cho told The Hoya.

Jesuit Identity, Academic Rigor

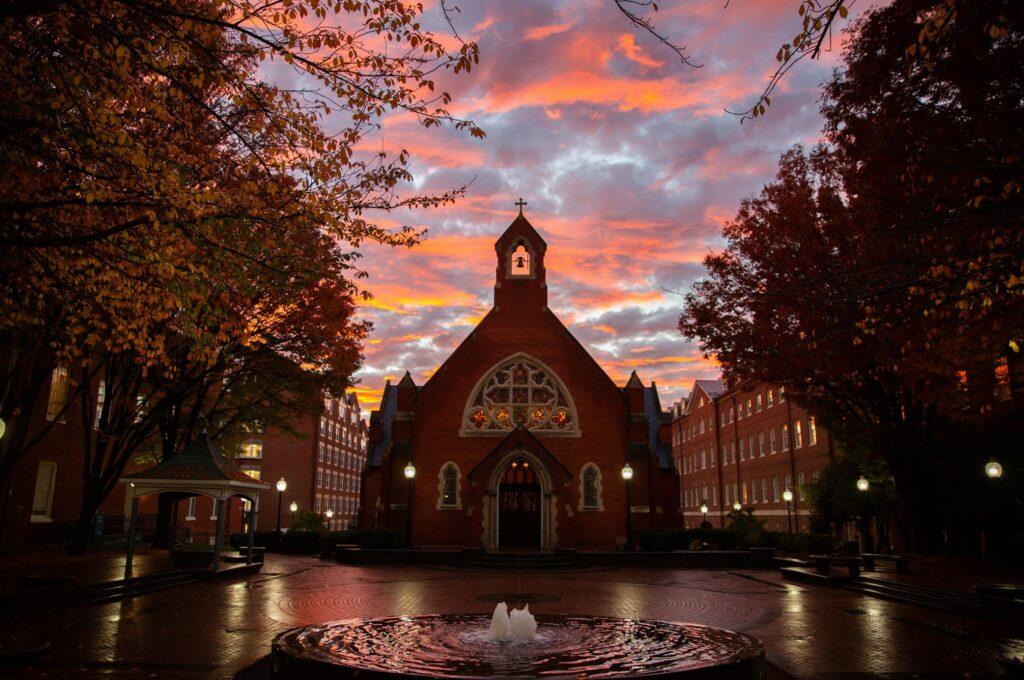

Georgetown University was founded in 1789 by Archbishop John Carroll, making it the oldest Catholic and Jesuit university in the country. Since its establishment, Georgetown has welcomed students of all faith backgrounds, and roughly 20% of the student population during its first century were Protestant.

Carroll’s commitment to Jesuit values guided the trajectory of the university, most notably his loyalty to “cura personalis,” or educating the whole person.

The Jesuits, also known as The Society of Jesus, still contribute to Georgetown’s campus community today. Three of the 21 tenure faculty in the theology and religious studies department are Jesuits, many of whom teach courses across various departments, including English and the sciences.

Georgetown has also been a trailblazer among Catholic academic institutions in terms of religious diversity. In 2016, it became the first American university to employ a Hindu chaplain, and in April 2023, it opened the first mosque on a U.S. campus.

Cho said she incorporates the discussion of real world problems to add a new dimension to theological coursework in her “The Problem of God” course.

“I try to encourage students to apply theology and theories of religion to read and interpret social problems. I bring up a lot of social issues in their context — racism and gender issues, post-colonialism and Orientalism,” Cho said.

Like most religious universities, Georgetown has a theology requirement for all students, regardless of their field of study. Yet the freedom granted to students — choosing a section based on topics covered or professorial interests — does not exist at all Catholic universities.

The University of Notre Dame, for one, has a theology requirement that mandates studies of Christian scripture and doctrine.

Danner said that the varying coursework among “The Problem of God” classes allows for a diverse array of approaches, and it can often mean students taking additional religious studies courses on faiths that are of a different background than their own.

“When you’re teaching a second, or 2000-level course, you really have no idea what the students coming in may or may not have been exposed to,” Danner told The Hoya. “I often have to kind of read, or cover things that I cover in my Problem of God course just to make sure again that people are on the same page.”

Jonathan Ray, a professor in the theology and religious studies department, began teaching Problem of God in 2006 when he arrived at Georgetown. Centered around his own expertise in European religious history, his course profiles a history of major themes of religion in the West, mainly focusing on Judaism, Islam and Christianity.

“My training is in the history of religions, so that’s how I think of things,” Professor Ray said in an interview with The Hoya. “I think of things chronologically, and I’m interested in the way different groups interact with each other.”

Over the years, Georgetown’s Problem of God requirement has diverged from traditional religious instruction at the university level. A 1999 New York Times article profiles professor Theresa Sanders, who shared with students writings of a medieval nun describing Jesus as maternal, showing the historic trend of professors taking creative liberty with their curriculum.

For students like Bonnie Sneider (CAS ’25), a theology and religious studies major, the vast array of complex theological classes offered is a nod to Georgetown’s wide view of religion. However, she does wish that a basic introduction to religion class was taught to help students gain a succinct, general understanding of major world religions.

“I think the classes can be kind of niche, which usually is a strength because they’re more engaging,” Sneider told The Hoya. “But then sometimes I do wonder if my basic knowledge is there or not.”

Danner said that, likewise, she feels the Problem of God curriculum could benefit from both a general set of standards, and a required second class taken senior year to solidify concepts for Georgetown graduates to take with them.

“I think there are some advantages to having at least some minimal shared goals in terms of some of the course so faculty can get a better sense of what students are grounded in,” Danner said. “I would love to see there be a follow-up to Problem of God or I would love there to be some kind of required coming back to theological issues.”

Shaping the Georgetown Experience

Outside of the administrative aspects of the course, introductory theology classes can be an invitation for further coursework, culminating in a minor or even a major in theology and religious studies, or a religion, ethics and world affairs minor offered at the Berkley Center.

Salma Benchekroun (CAS ’27), a first-year student taking “The Problem of God” this semester, said her experience thus far has encouraged her to think in new ways about religious traditions and their modern implications.

“I do think that theology was something that I was excited to study coming to Georgetown,” Benchekroun said. “When I say that I’m interested, I don’t think it’s something that I necessarily want to study or go into, but it is definitely something that I appreciate that the Georgetown curriculum requires us to look into.”

Sneider said that the same can be said of other first-year courses, including her “Human Flourishing: East and West” Ignatius seminar, a small course composed of only first-year students intended to delve into a specific set of ideas. She said her seminar professor influenced her to major in theology and religious studies.

“She said on the first day that she would convert one of us to a theology major, and I ended up being that person,” Sneider said.

Outside of the classroom, Danner said that she encourages her students to take advantage of their time at Georgetown by expanding their existing experiences with theology, including through attending a religious service on campus apart from their own tradition.

“I absolutely try to open that door, and I’ve seen it can be intimidating for some students, but for some students it opens up a really wonderful place where they might know a friend is Muslim or Jewish or Christian and they go together to these services, and it can be very powerful for students,” Danner said.

Sneider, who is also on the pre-medical track, said her experience with a wide array of theology courses has impacted the way she views patient care as an aspiring health care professional.

“I feel like I found more purpose in it as time has gone on, like I have kind of connected learning about beliefs and traditions to grieving processes and this is important to understand when you go into a field like medicine,” Sneider said. “Families’ belief systems are kind of critical to how you approach your care.”

Cho said that the “The Problem of God” experience can often challenge her students’ preconceived notions about class, including those of some expecting a “Sunday school”-style class. She seeks to expand their horizons on how religion and society are closely intertwined.

“It’s mostly about opening yourself to different insights. Religion and society are closely related. You can’t think about religion without thinking about society and its context,” Cho said. “Religion is always engaging with social problems in many different ways.”

Danner also said taking “The Problem of God” can equip students to address the tough yet necessary topic of the intersections between faith and politics.

“What are you not supposed to talk about? Religion and politics,” Danner said. “What do we really need in the U.S. right now? To be able to talk about religion and politics. I frame it as a kind of interpersonal, civic and professional skill, to be able to talk about religion and meaning and purpose.”

Choose Your Own Adventure

Though some students come to Georgetown eager to begin their “The Problem of God” coursework, for many others it is another box to tick in their first year. For some of those students, including Sophia Pezeshkan (SFS ’26), the course makes a strong impact, even if it doesn’t result in a major or minor switch.

Pezeshkan’s section of the course surveyed theological thought across history, and she said that while she isn’t particularly interested in religious studies, she enjoyed the course.

“We started at the basis of religion and where it stems from, starting from animism and working our way up to religions of the modern world,” Pezeshkan told The Hoya. “I think, in a way, theology is fundamental to our education the same way you would say that history or philosophy is, because it’s the basis of a belief system.”

Benchekroun said she was aware of the diverse approaches to the course, though it was ultimately scheduling and not content that motivated her to choose her section.

“I had heard that Problem of God was one of those classes where if you had a certain professor with certain religious beliefs or cultural affiliations, the way it was taught, or what you would learn might be different,” Benchekroun told The Hoya.

Still, Pezeshkan said she felt that students should align their enrollment with their interests in a professor’s work, as that may be indicative of what that section of the course would cover.

“I would base my selection not only off of a professor’s beliefs or specialities, because that is not the only thing you learn, but on what the syllabus or the course plan would involve,” Pezeshkan said.

For Ray, who specializes in medieval and Jewish studies, the diverse perspectives present in “The Problem of God” classes are highly valued and important.

“Getting people who are going to have a major in nursing and health sciences and getting people who are going to have a major in Classics and a major in government in a conversation together, I think is a really good opportunity for all of us to realize, ‘Wow, there’s a lot of different ways of looking at this stuff,’” Ray said.

“Those really big questions aren’t on the final exam at Georgetown,” Ray added. “But those are things that hopefully people will think about deeply for the rest of their lives.”