“Nuremberg,” written and directed by James Vanderbilt, is a political throwback that tries for prestige but ends up with just a bit too much polish for its own good. A dialogue-driven drama, “Nuremberg” — which adapts Jack El-Hai’s 1945 novel “The Nazi and the Psychiatrist” — explores the moral aftermath of World War II through the lens of the layered dynamic between psychiatrist Douglas Kelley (Rami Malek) and Nazi leader Hermann Göring (Russel Crowe).

For most of its 148-minute runtime, the audience follows our two leads, who are locked in a prison cell where Kelley is assigned to keep Göring alive long enough to face his trial at Nuremberg. The discussion in the cell becomes almost a cage match in which we see a slow, deliberate battle of wits, with a mixture of stately dialogue and a charismatic performance from Crowe. Although the basis here promises moral complexity, with a glance at how these two figures’ intellect is rivaled only by their narcissism, Vanderbilt delivers a film that feels more handsomely watchable than anything: entertaining, well-acted, but maybe a little too clean around the edges.

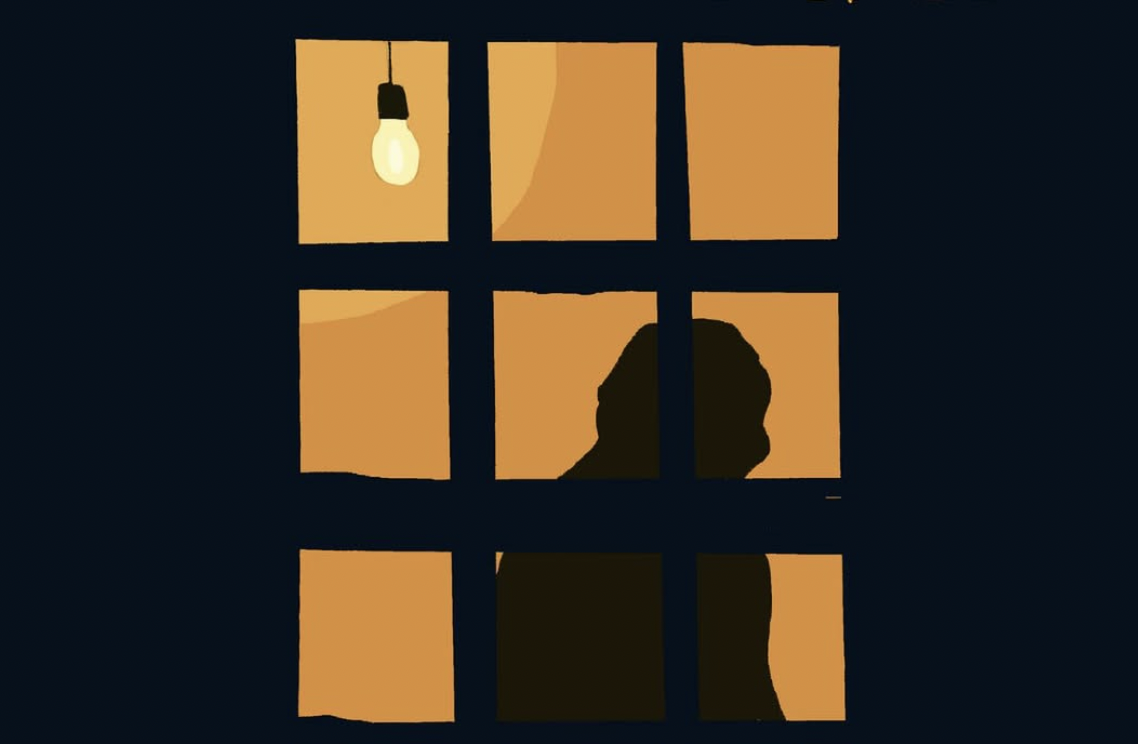

The film mixes scenes both inside and outside of Göring’s cell with deliberate, but perhaps slightly slow, pacing. Vanderbilt — alongside cinematographer Dariusz Wolski, known for his work on the “Pirates of the Caribbean” franchise — paints the world in browns and grays with dim institutional lighting. Although this combination might sound like the makings of a boring film, the presentation here is professional and confident, clearly an effort to bring gravitas to modernize a bygone film archetype, just with the color grading of an HBO limited series.

Crowe’s and Malek’s performances make up the core of the film, with their line deliveries being arguably more important than the script itself. As Göring and Kelley spar verbally, Crowe manages a convincing accent, alternating from English to German, which he learned for the role. Furthermore, Crowe strikes a perfect balance between charismatic and commanding, giving one of his better performances as of late, and somehow manages to feel uncomfortably human, a chilling feat given all of Göring’s evil deeds.

Given the morally complicated subject, the dedication to learning an accent and a new language, and promotional quotes like “a powerhouse return to Oscar form for Russell Crowe,” the campaign for Crowe’s fourth Oscar nomination seems inevitable. In the context of the film, though, Crowe’s Göring reminds us of the unnerving reality that such historical villains had personal lives, with sections that touch on Göring’s family and Kelley’s developing relationship with Göring’s daughter.

Beyond this relationship, Kelley feels stranded between two worlds and, while undoubtedly intelligent, his character lacks depth. The script has a half-baked portion hinting that Kelley, whose fascination with the prisoners might stem more from ego than from empathy, may share in Goring’s narcissism, but these ideas remain sketches rather than fully formed arguments. Also, Kelley is repeatedly shown to be a hobbyist magician, often performing tricks for Göring, with his magician’s sleight of hand mirroring his deftly deceptive use of language. However, Malek isn’t given any of the ambiguities that Crowe explores so well in his role as Göring.

The film’s courtroom climax demonstrates Vanderbilt’s most daring choice: Evidence during Göring’s trial includes real footage from concentration camps. This scene is devoid of any score, and seeing the expressions of the cast shift as they uncomfortably try to reconcile what they know about Göring with the horrors they are seeing on screen is when “Nuremberg” actually reached meaningful resonance for me. This scene feels raw and heartbreaking, and I was left wondering why the rest of the film feels so much more overwritten compared to this one, authentic instance.

Tonally, Vanderbilt aims high with dense but accessible dialogue, quick exchanges and a certain measured elegance in how the film moves. But this same calculated precision sometimes works against “Nuremberg.” The more the film tries to convince me of its weight and deeper messages, the more I can’t help but notice the overproduction. This makes it feel like Oscar bait by design, but, in actuality, it’s a bit too conventional. In the end, Crowe’s performance alone should be enough to fill theaters, and Vanderbilt’s steady direction is visible throughout the runtime. However, the film’s attempt to blend scenes full of tension with emotional stakes never truly connects, making “Nuremberg” a film that is easy to appreciate and even easier to finish.