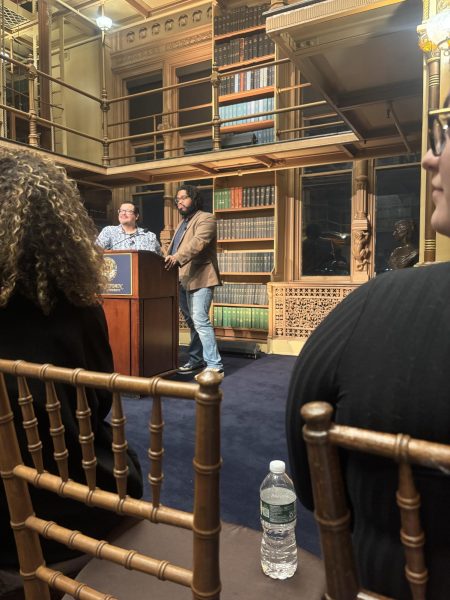

Two poets imparted their perspectives on the messiness of the human experience and dispensed career advice to young writers through a poetry reading event in Georgetown University’s Riggs Library on Jan. 21.

The Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice at Georgetown — which focuses on the exploration of the arts and literature through public events, fellowships and creative writing classes — hosted Eduardo C. Corral and Tyree Daye to discuss their experiences writing and editing poetry. The evening marked the third event in the Lannan Center’s 2024-25 Readings and Talks series, which brings poets and writers to Georgetown to share their work and discuss their process.

Corral, a poet and educator at Washington University of St. Louis, said his parents enriched his career in the opening of his reading works, which spanned his published poetry collection as well as unreleased poems.

“The fact that I am a son of Mexican immigrants is very important to me, my body of work and my career as a poet and as a professor in the United States,” Corral said. “Everything I do is stitched and made beautiful by their sacrifice and their presence in this country.”

Corral, who grew up in Arizona near the Sonoran Desert, added that a long sequence in his second book explores the perspectives of migrants versus their perception by the U.S. public.

“When we talk about immigrants in this country, we talk to them and talk about them in physical terms — here to take our jobs, here to do crime, the physicality of their existence is a threat,” Corral said. “So in this sequence, I internalize and center their thoughts, their emotions, how one thought branches into something else to capture the interiority of these people as they navigate the Sonoran Desert.”

Hans Yang (SFS ’28) introduced Corral and said his work illuminates the experiences of refugees and the layered conflicts that occur at the border.

“I had a visceral reaction to the similes and language that he used,” Yang said. “His work has forever changed the way I observed the intersections of culture and loss.”

Both Corral and Daye, a poet and assistant professor at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, interwove their readings with personal musings on their lives and careers before taking questions from the audience and participating in a book signing.

Daye said he matured as a writer, which he feels is reflected in his most recent publications.

“The speaker of my poems has finally caught up with me, meaning I feel like I’m the same age now,” Daye said. “In my earlier collections, the speaker is 12 or 13, but now the speaker is my age, which has been difficult, but it’s really nothing to hide behind.”

Corral said that, in ordering his poems for his collection, he works toward eventual cohesion even if the order doesn’t make sense at first.

“I give each poem three or four identities or shadows, which allows me to actually see the poems from different angles, so I can shuffle and order them in surprising ways,” Corral said. “One thing I’ve appreciated is the saying that poets only see the similarities in their work, while readers see the differences.”

Daye said ordering a poetry collection is a visual exercise that relies on the cohesive theme of the book and braids themes together.

“I like to find images in my poems and figure out how they show up differently each time, in a way to build upon that, in a way to stretch that across different poems,” Daye said. “So if I have a poem that kind of deals with my mother, I think about how the three or four poems are between another poem and how they also may all be in communication with each other.”

Corral said the freedom in writing a poem is in the imperfection involved in the process.

“Language is a magnificent but flawed tool because it cannot equal, it can only approximate,” Corral said. “Having that freedom is amazing because that failure belongs to language itself, not to you as a writer, which frees me to get as close as possible.”

Daye said the ending of the poem is the most important part, as it culminates the storyline of the piece.

“One of my teachers said that the ending of a poem should feel like a door that’s been opened,” Daye said. “It should be kind of like something you are able to walk through and ponder, where everything has changed.”