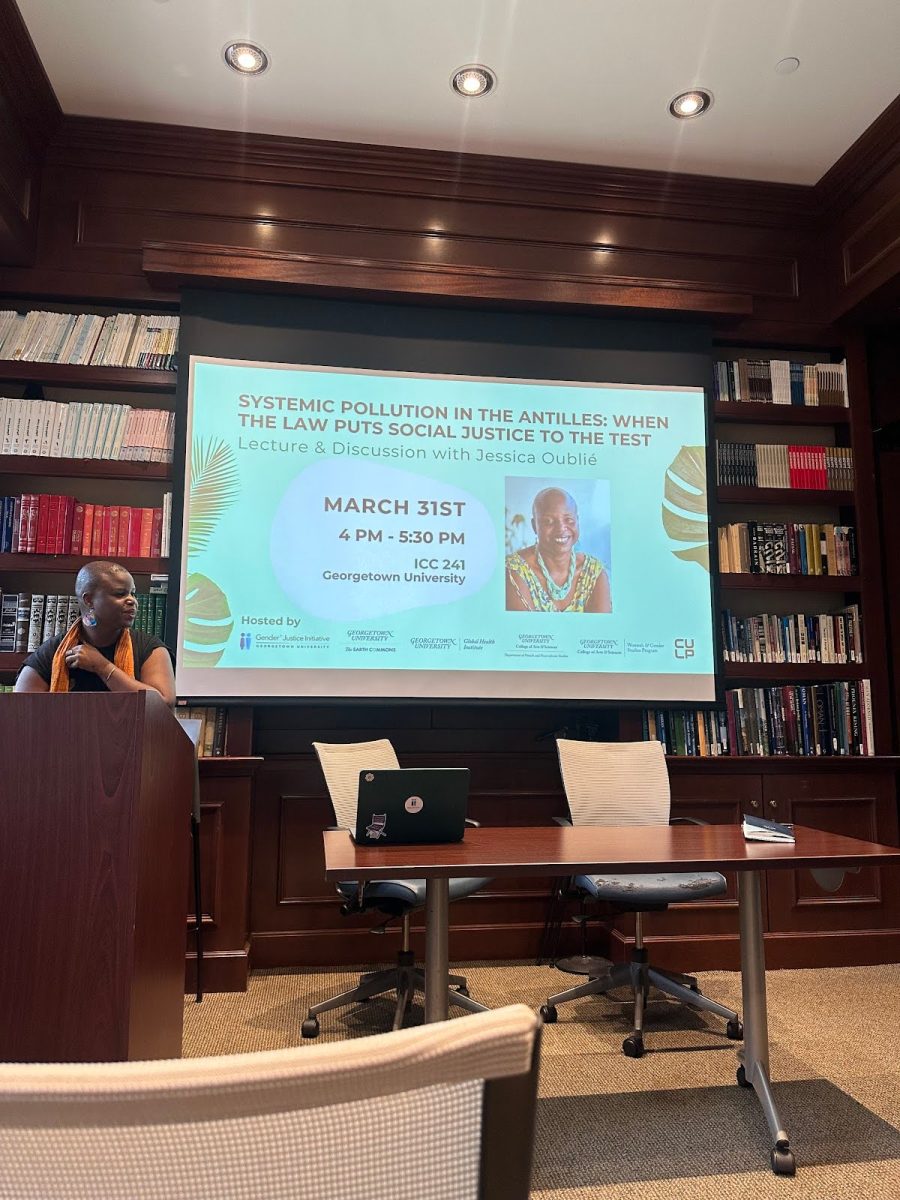

An author and educator detailed the long-term effects of chlordecone, a toxic insecticide used for decades in the French Antilles — the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe — at a Georgetown University event March 31.

Jessica Oublié, an author who researches the unjust legacy of chlordecone, analyzed the historical adoption of this insecticide in the French Antilles at the talk, drawing attention to the injustices its residents faced. During the event, Oublié also explored the use and legacy of organochlorine products, organic compound-based pesticides, on the islands.

Oublié said lasting effects of chlordecone can be seen throughout the ecosystem.

“What you see today is that chlordecone has really polluted not just the soil but also waterways, so you see contamination of the whole food chain,” Oublié said at the event.

The use of chlordecone began in the 1960s to combat the banana weevil, a beetle that destroyed banana crops until organochlorine products effectively terminated the insects. With this, farmers used the insecticide generously in the Antilles for decades.

Some organochlorine products — including chlordecone — are persistent pollutants, meaning they accumulate in the environment, humans and animals. The high amount of chlordecone used in the French Antilles is expected to persist for 600 to 700 years.

Oublié referenced a 2018 study that found 95% of the population of Guadeloupe and 92% of Martinique had evidence of contamination in their blood due to the high presence of chlordecone.

Melyssa Haffaf, executive director for Georgetown’s Gender+ Justice Initiative, a hub addressing the issues in gender inequality and discrimination, said the effects of pollution disproportionately affect women.

“The effects on reproductive health and increased cancer risks are particularly alarming, with the potential to harm women and their children for generations,” Haffaf wrote to The Hoya. “Additionally, given that women in the region are disproportionately single mothers, caregivers and leading advocates for public awareness, their role in this crisis extends far beyond personal health impact.”

Although chlordecone was banned in mainland France in 1993 for being an endocrine disruptor and possible carcinogen, banana farmers in the Antilles used chlordecone procured from illegal imports through the early 2000s.

In presenting a study from the early 2000s, Oublié said chlordecone-contaminated sweet potatoes exported to France were destroyed before they reached the mainland.

“After this, there was the belief that there are two justice systems, one making sure French citizens in mainland were looked after, whereas Antillians had been exposed to that pesticide for many decades and nothing had been done to address the sanitary and health issues at stake here,” Oublié said.

In exploring government responses to chlordecone — called Kepone in the United States — Oublié said the United States completed extensive de-pollution efforts faster than France, which took 13 years to ban the sale of chlordecone completely and 31 years to start de-pollution efforts.

“De-pollution, do a fishing ban, sales ban, analyzing research on water, vegetables, meat, epidemiological research, then an investigation done by the Senate,” Oublié said. “This difference is pretty shocking.”

Josh Chang (CAS ‘26), a student who attended the event, said the French Ministry did not appropriately address these health concerns that result from chlordecone.

“Despite having knowledge of chlordecone’s toxicity and persistence, the French Ministry of Agriculture approved the use of chlordecone due to pressure from the corporate/Béké lobby, highlighting the importance of building local movements by and for the community in the face of a state that refuses to address the very issues it caused,” Chang wrote to The Hoya.

Haffaf said the legacy of chlordecone exemplifies other systemic inequalities such as gender injustice.

“Women in the Antilles face distinct and disproportionate impacts — both in terms of health, environmental and economic consequences — that have been severely under-researched,” Haffaf wrote.

Haffaf said reparations for people impacted by the pesticide should be made with a decolonial lens.

“Without a gender-focused approach, reparations risk perpetuating the very inequalities they seek to redress,” Haffaf wrote.