A professor of medical oncology and chief of experimental therapeutics at the Yale School of Medicine lectured at Georgetown University on navigating the Valley of Death in clinical drug development Jan. 17.

Patricia LoRusso, the professor, helped to develop 28 FDA-approved cancer therapy drugs, successfully passing through the Valley of Death each time. The “Valley of Death” refers to the transition phase of drug development from preclinical research to clinical trials, during which research may fail to result in a usable therapeutic.

Dr. Louis Weiner, director of the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and lecture sponsor, said that resolving the issues in this process requires multifaceted collaboration between academics in universities like Georgetown, private companies and regulatory agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

“Most academic institutions like Georgetown can make and test preliminary ‘tool’ compounds, but effective drug development requires a deep understanding of the competitive landscape, the ability to secure appropriate intellectual property protection for the concept and agents being developed and the development of various laboratory assays to assess the potency, targets and potential side effects of the drug,” Weiner wrote to The Hoya.

“It is really quite a gauntlet, and few if any universities have the bandwidth to successfully traverse this valley of death.”

Dr. John Marshall, director of developmental therapeutics at Lombardi, said he believes that academics often face difficulty obtaining the support needed to get their products through trials and on the market, in contrast to large pharmaceutical companies.

“The biggest change here is how large pharma companies are doing most of the major drug development, making it increasingly hard for academic teams to move products forward,” Marshall told The Hoya. “It is big business in addition to big science, making it hard for academics to compete.”

While collaborating with large pharma companies can potentially help novel drugs pass through the Valley of Death, researchers with novel cancer therapy drugs must also demonstrate their efficacy to attract funds from these companies.

Drug testing is an iterative process, as it involves making adjustments to determine the optimal dosage levels and drug combinations for patients. The goal is to find a biologically effective dose, or the dose at which disease regression is maximized but patient side effects of cancer therapy drugs like anemia and nausea are minimized. Problems can arise because the biologically effective dose exceeds the minimally important difference, the smallest difference experienced by the patient in treatment that could cause a clinician administering the trial to change the treatment in some way.

The process of drug development has evolved to become more streamlined in recent years, which means that the potential of potential drug treatments may be recognized earlier and escape the Valley of Death.

Marshall said having a targeted approach to researching and administering drugs may be helpful.

“The biggest shift has been in precision medicine, where instead of treating all cancers the same, we are recognizing how they are different with different therapies for the subtypes,” Marshall said.

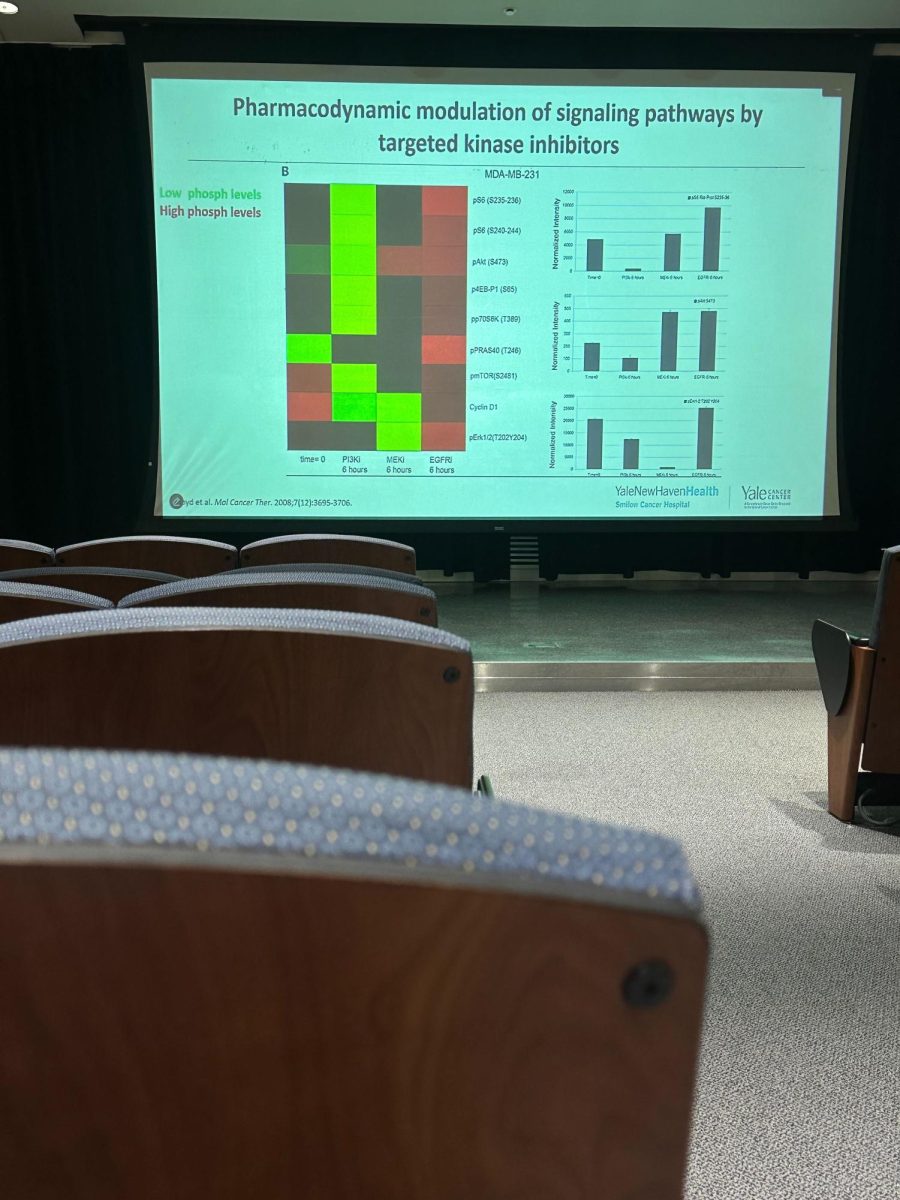

In her lecture, LoRusso noted how cell signaling pathways causing cell growth have been one of the main targets for drugs, while transcription factors, the regulatory proteins that control gene activity, hold great potential as targets for novel cancer therapy drugs. By leveraging new technologies such as AlphaFold2, an artificial intelligence program that reveals the structures of complex proteins, researchers can gain a fuller spatial understanding of these proteins and develop drugs that are more targeted for specific diseases.

Even with her success in navigating the Valley of Death, LoRusso said her work is far from done.

“None of these drugs have been 100% successful against the disease,” LoRusso said.