Jeffrey Ngo is a leading activist in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement and a doctoral student at Georgetown University studying history. This feature is the first in a series of in-depth profiles about Georgetown students and their stories.

Jeffrey Ngo’s career as an activist began in 2003, when he was seven.

At the time, his home city of Hong Kong was navigating a period of turbulence. The SARS outbreak had spread across much of Southeast Asia, killing close to 300 Hong Kongers and infecting nearly 2,000. Only weeks after the health crisis began to subside, Hong Kong plunged into a political one.

On July 1, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators packed the plazas and throughways surrounding Hong Kong’s government headquarters to protest a newly introduced national security law. Laden with vague language and sweeping edicts, the law prohibited secession and sedition against the Chinese government, threatening the long tradition of civil liberties enjoyed by the city’s residents.

In 1997, the United Kingdom transferred control of Hong Kong to China. Part of the handover agreement between the two powers stipulated Hong Kong retain a level of autonomy and freedom until 2047 under a one country, two systems model.

Ngo recalls Hong Kongers’ sharing a cautious optimism after the handover.

“There was a sense that Hong Kong would not only attain democracy but be the guiding light for democratic change in the rest of China,” Ngo said in a Zoom interview with The Hoya. “It was still possible to see a Hong Kong government led by a Hong Konger and somewhat responsive to public opinion.”

Not everyone shared this idealism. For some, the handover was Hong Kong’s death knell — a powerful, ascendant China bent on expanding party control would gradually erode Hong Kong’s democratic institutions and civil liberties well before 2047, and no one would stop it.

“There was a lot of talk about [the handover] being Hong Kong’s endgame,” Ngo said. “But the first five, six years sort of proved that wrong.”

During the summer of 2003, half a million Hong Kongers fended off Beijing’s first major incursion.

Ngo remembers the day well despite his young age. He attended the protest with his family, who guided him through the throngs of protesters. The sweltering, subtropical heat beat down on the crowds, which seemed unending. He remembered the anger and pride of his fellow Hong Kongers — it was Ngo’s first taste of what he calls “the struggle.” The demonstrations awakened him to Hong Kong’s existential battle to protect its freedom, inspiring him to join a fight to which he would dedicate his life.

The Emissary

Ngo was born two years before Hong Kong’s handover to China. He lived out his childhood in a high-rise apartment in the district of Shatin, a residential neighborhood nestled between parks and nature reserves.

Ngo was born into a middle-class family with a strong Hong Kong identity. His father, now retired, was a longtime professor at a local university. Like many other middle-class families in Hong Kong, Ngo’s family was firmly pro-democracy. His parents served as his gateway into the struggle.

Ngo immersed himself in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement after 2003. He began following the news attentively in grade school, in the same way many of his peers might have tuned into Sunday morning cartoons.

By secondary school, he became a regular on the pro-democracy protest circuit, participating in street rallies and marches across the city.

“Most of my classmates were more detached from the local political scene,” he remarked.

Every year on the fourth night of June, Ngo gathered with hundreds of Hong Kongers at Victoria Park, candle in hand, to commemorate the anniversary of the Chinese government’s bloody crackdown against pro-democracy protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989. According to Ngo, the episode has special salience for Hong Kongers, who are fighting to preserve the liberties Tiananmen’s victims had fought for, but failed to acquire.

In 2013, Ngo moved to New York City to study journalism at New York University. He hoped to become a political journalist, documenting the developments in his city and holding its politicians to account.

Ngo enjoyed his time in New York. The city reminded him of home — dense, diverse and dynamic. The local obsession with football, however, was one cultural rift he found difficult to cross.

He made friends and did well in his classes. His interest in politics led him to spend a semester at NYU’s campus in Washington, D.C., his sophomore year.

That semester, he began to lose his interest in journalism. For one, the market for a journalism internship was unforgiving. (“It’s stupid because if you want an internship you need experience, but if you never get an internship in the first place, you can’t get experience,” he griped.)

He also grew wary of journalism’s shortsightedness.

“Obviously journalism has a lot of value, but most of the time it doesn’t allow you to go very deep into things. The attention span is relatively short, and there is a lot of pressure to deal with a lot at the same time,” he said. “If I wanted to understand Hong Kong’s problems, I needed to take a longer view.”

And so, he switched to history. His academic switch, like many of the major changes of his life, was inspired by a new round of political upheaval in Hong Kong.

In late August 2014, the Chinese government introduced an electoral rule requiring that candidates for the Hong Kong chief executive be prescreened by the Chinese Communist Party. The new regulations represented an undisguised assault on Hong Kong’s democratic practices and rule of law.

“Whoever wins [the election] is someone Beijing is already fine with,” Ngo explained. “People were outraged — this is crazy, this is not democracy. This is what happens in Iran.”

Protests exploded in September, with tens of thousands of demonstrators taking to the streets. Ngo observed these developments from afar and decided to take action. He began organizing protests in D.C. and New York. Every Thursday night throughout the fall, he took the overnight Greyhound bus to New York to organize protests and marches over the weekend.

“I would meet people and host smaller rallies [in New York],” Ngo said. “On weekdays I would come back to D.C. for my internship and my classes.”

For the first time, Ngo was no longer just a participant, but an organizer, and a notable one. He caught the attention of protest leaders in Hong Kong and U.S. lawmakers. He became friends with Joshua Wong and Nathan Law, two prominent pro-democracy advocates who, with Ngo, would be key leaders of subsequent protests in Hong Kong. That same year, Ngo had his first meeting with a member of Congress — now-retired Frank Wolf (LAW ’65) (R) of Virginia’s 10th district.

By December, however, the protests petered out. Nothing had changed. The government, unmoved by the demonstrations, kept the electoral changes in place and began undermining academic freedoms.

“There was still the hope that if we staged an unprecedented protest — one of the largest protests on Chinese soil since 1989 — maybe Beijing would budge,” Ngo said. “It didn’t.”

The defeat shook Ngo and many pro-democracy Hong Kongers, who were forced to reckon with the feasibility and sustainability of the one country, two systems model.

“In 2014, there was still hope that one country, two systems could work,” Ngo said. “In 2015, there was a lot of soul-searching.”

Ngo’s activism during the protests, however fruitless in the short term, launched him to the forefront of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy political scene. In 2016, Ngo helped Law get elected to the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, the city’s lawmaking body. The following year, Ngo undertook the duty of internationalizing Hong Kong’s cause by lobbying foreign lawmakers, writing op-eds and speaking at events. In due time, Ngo would soon face his biggest challenge.

Slipping

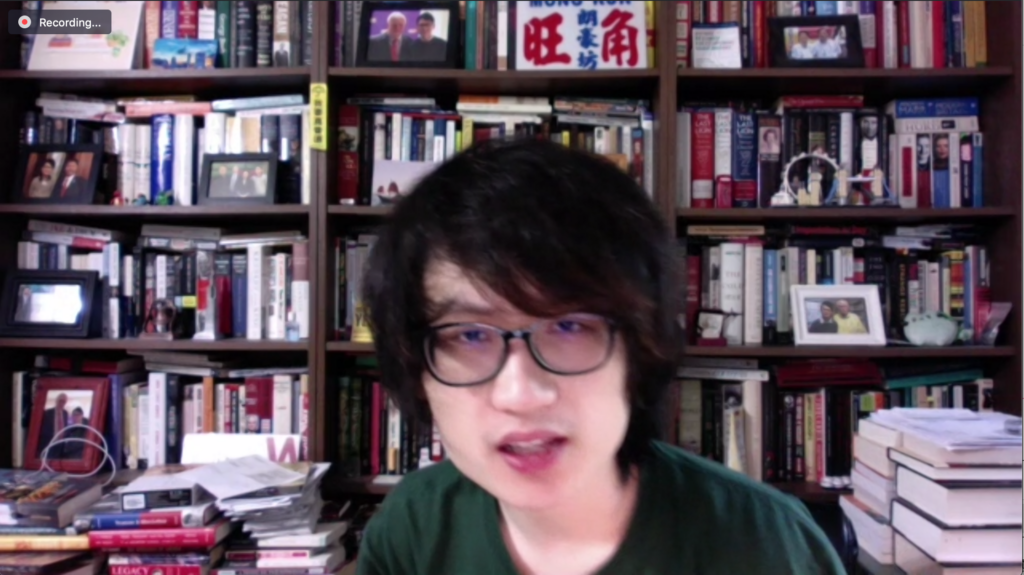

Ngo spoke with The Hoya via Zoom from his apartment in D.C. He started his doctoral degree in history at Georgetown in 2018 after finishing his master’s degree at NYU.

He sat in a swivel chair in front of a russet bookshelf that reached from the floor to the ceiling. The shelf was packed with books about history and politics. Books that were not afforded space on the shelf formed small, cluttered mounds in front of it. Ngo filled the remaining slivers of space on the shelf with knick knacks, photos with congressmembers and dignitaries and other personal mementos.

He sported a green T-shirt, wide, ovular glasses and an unruly pandemic haircut. Throughout the conversation, Ngo worked his way through a bowl of microwaved soup, taking breaks from his lengthy and detailed answers to take a sip or two.

One year before his conversation with The Hoya, Ngo was choking on tear gas on the streets of Hong Kong.

In the summer of 2019, hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers mobilized on the streets against another perceived attack on their civil liberties. This time, the threat took the form of an extradition bill put forth in the Hong Kong legislature, which would, under unclear pretenses, allow Hong Kongers to be extradited to China for a variety of crimes. The extradition bill was, at the time, the gravest threat to Hong Kong democracy, according to Ngo.

“It was an existential threat. The idea about what separates Hong Kong from China is the rule of law and judicial independence. A lot of that was going to disappear if the extradition bill passed,” he said. “In 2019, the feeling was that we were trying to defend what we always had, and we were trying to prevent that from slipping.”

Ngo spent every day that summer on the streets protesting. He and a cohort of friends from the pro-democracy party Demosisto assembled one of the city’s first rallies against the extradition law. He lobbied members of Congress, helping organize hearings and legislative action.

The protests became more dire and more violent as the summer progressed. Police used beatings, tear gas, and rubber bullets to disperse crowds. Protestors armed themselves with makeshift shields and umbrellas for defense.

“It was really something,” Ngo said, pausing and combing his hair with his hand, “being on the streets and getting tear-gassed and seeing how Hong Kongers fight back.”

As the protests evolved, so did the demands of the protesters. The government had to do more than withdraw the extradition bill to win back their trust and keep them off the streets. Protesters issued four new requests, including an independent investigation into police brutality and expanded electoral rights. The government dropped the extradition bill in September, but the other demands were not met. The protests puttered along throughout the following months.

The protests began to wane in the spring as the COVID-19 pandemic made landfall in Hong Kong. Police forces used the pandemic as a pretext for disbanding gatherings. Throughout the late spring and early summer, the protests teetered. In late June, they collapsed.

On June 30, the Chinese government passed a new national security law in response to ongoing instability in the city. The law, harsher than its 2003 predecessor, is an open-ended prohibition of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign powers against the Chinese government.

The law’s broad and vague terms make it a potent weapon against Hong Kong’s democratic institutions.

“It’s very open to interpretation and very open to abuse,” Ngo said.

The law flipped a switch. The protests mellowed, and the streets emptied. Once-vocal critics of the Chinese government quieted down. The new law effectively quashed the pro-democracy protests, eroding Hong Kongers’ civil liberties in the process.

“A number of [pro-democracy] groups have either suspended their operations officially or disbanded in Hong Kong,” Ngo remarked. “The situation on the ground changed very rapidly.”

The Long View

Ngo has no plan to return to Hong Kong after the passage of the national security law. His pro-democracy activism and vocal opposition to the Chinese regime make him a prime target for security forces, who have swiftly and forcefully disarmed dissent in the city. If he were to return, Ngo fears he would be detained upon arrival.

“It would not be safe for me to [return],” Ngo said. “The situation on the ground in Hong Kong is pretty grim. My friends are getting arrested and prosecuted. They’re worried.”

Hong Kong authorities have been conducting mass arrests since the law’s passage in late June. Many of Ngo’s friends and colleagues have already been seized or forced abroad. Law was forced to flee the city in early July. Agnes Chow, another well-known Hong Kong activist, was detained by police Aug. 10 for allegedly “inciting secession,” the same day authorities arrested the owner of a notable pro-democracy newspaper.

Within the span of a summer, civil disobedience in Hong Kong was extinguished. The city’s civil liberties — everything Hong Kongers had been fighting to preserve since 1997 — have been buried, its independence curtailed.

Despite Hong Kong’s new bleak reality, Ngo is holding onto some hope. He believes the United States and other global powers are invested in protecting Hong Kong from an overbearing Beijing. To be hard on China has become politically savvy, and Ngo expects U.S. politicians to fight Chinese expansion on all fronts, including in Hong Kong. People, he says, need to consider the long view.

“There are larger structural forces at work that create a more favorable international situation for the Hong Kong cause,” Ngo said. “When I first started, it was so hard to get anyone interested in Hong Kong.”

Since the passage of the national security law, Ngo has continued advocating for Hong Kong from D.C., lobbying lawmakers, posting on social media and continuing his research.

“If you take the long view, it is hard to make a case that what I’m doing is not helpful to Hong Kong. This is what I tell myself,” he said. “That’s why I will keep doing what I do.”

Ngo’s hope for the future, however lofty it may appear, is undergirded by a more universal worldview. Life for Ngo is a sequence of serendipitous moments. Nothing is fixed, and everything — preferences, politics, power — can be changed by those who will it or the circumstances around them. Perhaps the only certainty, Ngo believes, is that society always edges toward justice.

“I would say I’m an optimist, not a naive one. I just believe that history moves generally towards more humanity,” he said, pausing and staring down at his soup. He looked up and grinned, “You know what I mean.”