Although a recent focus on improving teacher quality has elicited marginal improvements in the D.C. Public Schools system, structural problems of safety and security continue to pervade the city’s schools, leaving significant room for improvement in the District’s education strategy.

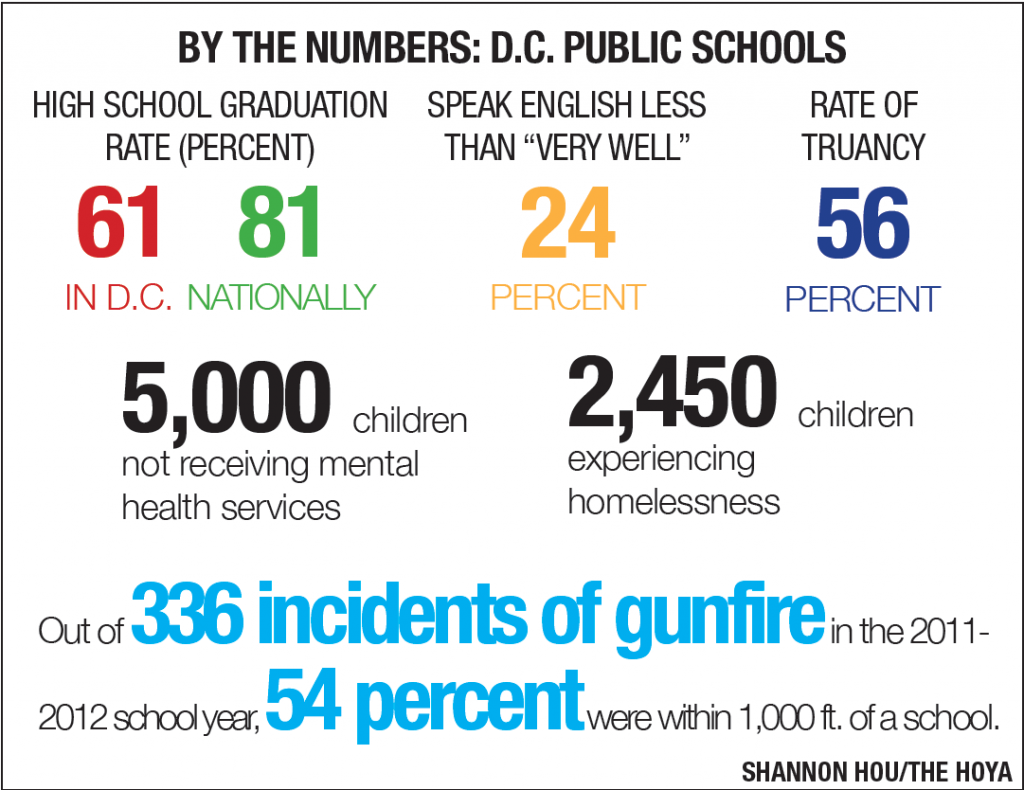

The high school graduation rate in Washington, D.C., was 61 percent in 2014, well below the national average of 81 percent. For public schools in particular, the rate lagged behind at 58 percent, while public charter schools graduated 69 percent of their students, which, though better, registered a seven percent decline from 2013.

Eight years after D.C. Public Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee ushered in an era of radical change, the situation of the DCPS system remains far from rosy.

Rhee, who was appointed chancellor in 2007, focused on improving the quality of teachers in the District, contentiously closing 23 schools in 2007 for poor performance, firing 36 principals and publicly taking on teacher unions. Her successor, Kaya Henderson (SFS ’92, GRD ’07), has continued the practice, closing 20 schools in 2012.

“In 2007, 95 percent of teachers were rated good or great, and then … 12 percent of students in the eighth grade were reading proficiently according to the [National Assessment of Educational Progress],” a DCPS central office administrator who asked to be identified only by position said. “And there’s a disconnect between those two numbers. Certainly, the 95 percent of teachers who we said were meeting our expectations — that doesn’t mean that they didn’t care deeply about students, want the very best, or were trying very hard — but it certainly meant there was a disconnect between how we were defining those expectations and the outcomes that our students were having.”

To evaluate teachers more rigorously, DCPS implemented the IMPACT test in fall 2009, which utilized reviews from different evaluators, community involvement and test scores. The system drew criticism from Washington Teachers’ Union President George Parker for “taking the art of teaching and turning it into bean counting,” according to the Washington Post in 2009.

Although test scores have improved overall since Rhee took over, much of the increase occurred in a large jump from 2007 to 2008. Since 2008, math scores have increased — except in Ward 5 — but reading scores have not, dropping more than five percent in four wards; in 2014, just 23.8 percent of students in Ward 8 were considered to be reading proficiently at their grade level.

The continued struggle of the educational system indicates to educators that issues larger than teacher performance are at play.

Brian Becker, the assistant headmaster at Washington Jesuit Academy, a small private school for grades five to eight in the Michigan Park neighborhood in northeast D.C., believes a successful school derives largely from the support of a strong community and culture.

“Our character and education plan incorporates many Jesuit values, but basically talks about building a strong and responsible community,” Becker said. “It’s a culture, not a long list of rules. So I think that any school, to succeed, needs to establish a culture with clear-cut expectations, and then constantly reinforce and shape that culture.”

Yet this safety and security can be difficult to find in the poorer parts of D.C., which encompass most of the city east of Rock Creek Park. The percentage of students who qualified for free and reduced lunches reached 76 percent in 2013-2014 school year, and there were over 2,450 homeless children in the DCPS system in the 2012-2013 school year, according to a report by the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute.

The same report noted that, according to the Children’s Law Center, more than 5,000 children in the District who needed mental health services may not have received them.

Last April, while kids were on the Ludlow-Taylor Elementary School playground in the Capitol Hill neighborhood, a man was shot and killed across the street, although he was out of sight.

Such violence is not uncommon, often spilling over into school areas and robbing students of the security needed to focus on academic performance. In the 2011-2012 school year, urban.org reported that of the 336 incidents of gunfire in D.C. during the school day, over half took place within 1,000 feet of a public school.

“From a needs platform, students who are not experiencing the basic Maslow’s hierarchy of needs at home, vis-a-vis shelter, food, and safe environments,” Alexander Levey, assistant director of admissions and financial aid at the Upper School of Sidwell Friends School in northwest D.C., said. “They arrive into an academic classroom maybe not having all of the brain freedom to explore academic tasks. And that is the starting point. So it’s really important in those communities to make sure kids are feeling safe and secure in order to then start to learn.”

The violence may contribute to the city’s high truancy rate: 56 percent of high school students had more than 10 unexcused absences in the 2013-2014 school year.

Private schools like the Washington Jesuit Academy steer students away from neighborhood strife and towards a belief that college is an attainable goal, but the public school system is more vulnerable, and the charter school system, which provides marginally better test score results than public school systems do and which remains an integral part of the D.C. education environment, is no failsafe.

While 44 percent of school-age city residents are now enrolled in public charter schools, the second most of any city in the nation, according to the Washington Post, the schools are concentrated in Ward 1, leaving students in Wards 7 and 8, which have weaker neighborhood schools, with few options to commute to charter schools. The District does not have a school bus system.

Though the demographics of the average school in 2014-2015 came out to 67 percent black, 17 percent Hispanic and 12 percent white, individual schools generally do not approximate those demographics, with significantly greater percentages of blacks in Wards 7 and 8, Hispanics in Ward 1 and whites in Wards 2 and 3.

Building a strong and safe community might begin with addressing the problems of violence and underlying poverty, but schools have found other ways to incorporate culture and community into their classroom as well.

The city’s Hispanic population as a whole grew over 14 percent between 2010 and 2012, and 24 percent of students speak Spanish at home and speak English less than “very well,” which presents a problem for schools that have trouble successfully integrating such students.

Yet three bilingual schools in the District, as well as Cardozo High School’s International Academy, have turned the problem on its head, teaching students — often recent immigrants — content as well as English so they can graduate on time.

Other angles to building community include seemingly little things like improving recess through structure and inclusiveness, the goal of Playworks, a national company which operates in several D.C. schools.

Topher Anuzis, who worked as a coach for two years at Playworks and currently works in their D.C. office, clearly saw the impact the program had on the school community.

“In the school that I was [coaching] at for two years, I definitely noticed a decrease in bullying, and a decrease in fighting during the day,” Anuzis said. “The incident reports I had to put in the first couple months of my first year were out of control, but by the end of my second year, I rarely had to report a fight because they were happening so infrequently.”

Music, too, is seen as another way to improve community and culture in D.C. schools, which Becker believes are making real progress.

“They’re heading in the right direction,” Becker said. “As a parent of a three-year-old who is eagerly awaiting the results of the DCPS charter school lottery at the end of the month, I understand in a totally different way the high-stakes game that is raising kids in the city and providing for their education. If I didn’t think that schools were improving at all levels, it would be difficult to justify raising a family in the city.”

Brian Dillon (COL ’11), an English teacher at Key Academy, a charter school in Southeast D.C., acknowledged the difficulty of fixing the education system. Without one solution in particular to quickly fix the problems in the District, Dillon pointed to dedicated teachers and administrators as key to advancing the education system, noting that their willingness to implement and test a variety of solutions could eventually improve outcomes for DCPS students.

“It’s not like there’s a silver bullet, or a magic formula,” Dillon said. “There’s just a bunch of committed adults who work sixty hours a week, and are with the kids from 7:30 to 4:30 every day, who care a lot and make sure the work gets done. … [In the District,] there are thousands of adults and thousands of kids trying to make it better, and it’s really hard work.”

Correction: A previous version of this article identified the Washington Jesuit Academy as a charter school. It has been updated to reflect that it is a private school.