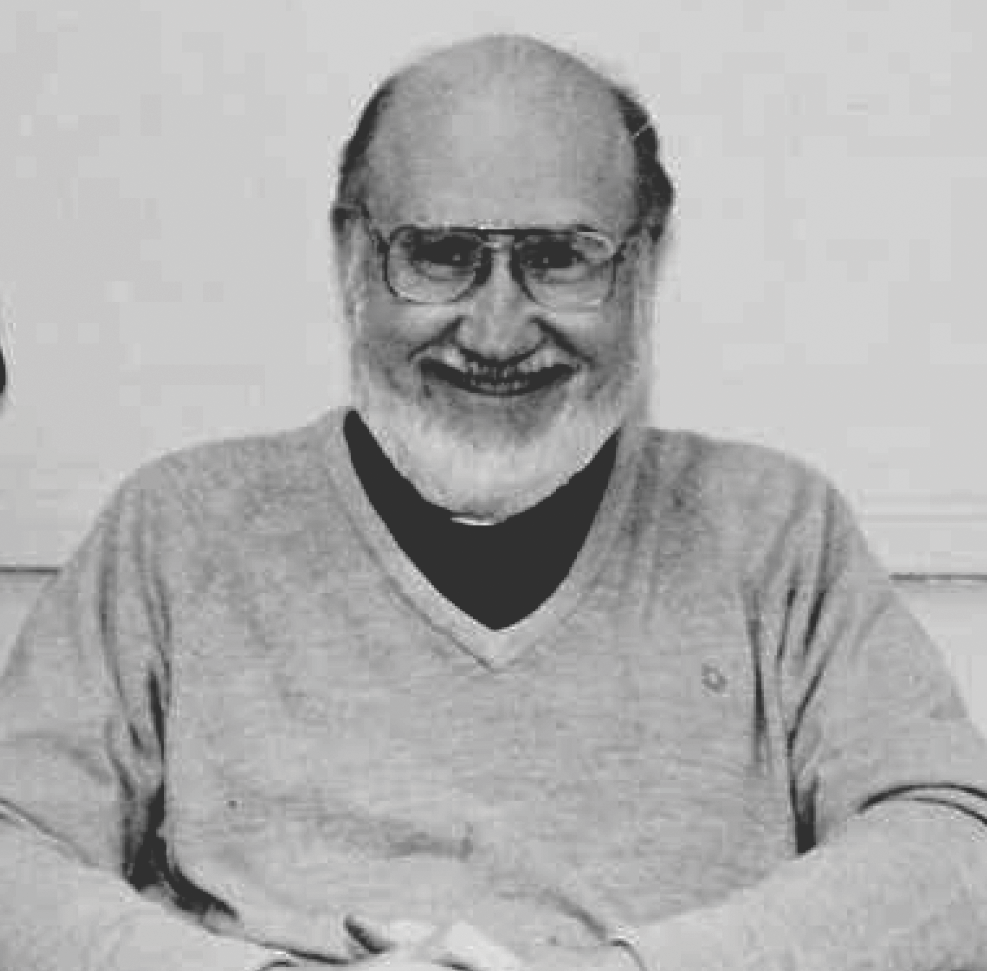

Christine Lyons saw Fr. Jack Kennington as a close family friend. Her neighbors on Manhattan’s Lower East Side saw him as a proud advocate for people struggling with drug addiction and a popular priest in the community throughout the 1980s. All the while, Brendan and Bridget Lyons, Christine’s children, knew “Uncle Jack” as a sexual abuser.

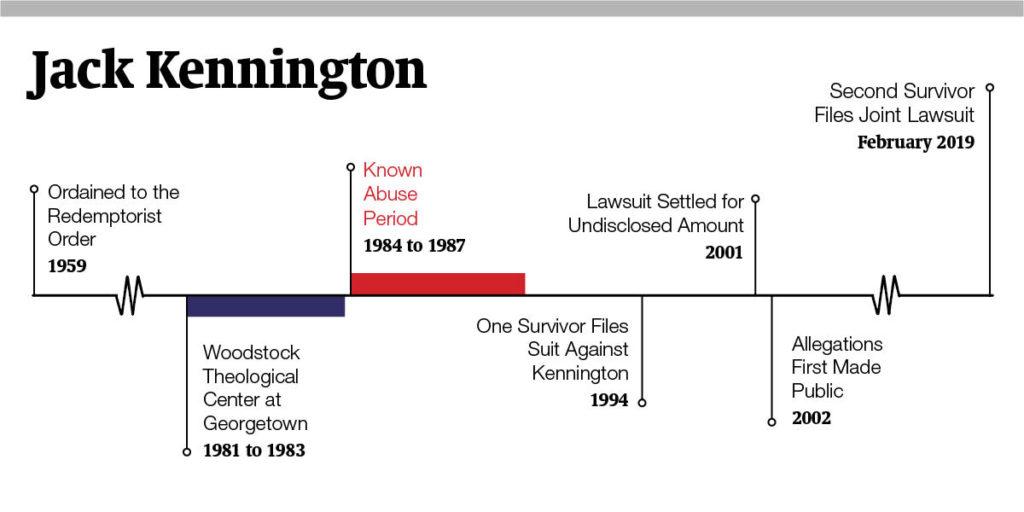

The abuse, which spanned from 1984 to 1987, began a year after Kennington, a member of the Redemptorist order of the Catholic Church, finished his assignment at the Woodstock Theological Center. Woodstock was a research center located in Ida Ryan Hall on Georgetown’s campus and was managed by the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus until the center closed in 2013.

The Lyons case resurfaced last month, when Bridget Lyons brought a joint suit against the Catholic Conference of Major Superiors of Men, demanding all Catholic orders release lists of known abusers within the church. The lawsuit follows her brother’s successful legal bid 18 years earlier. Brendan Lyons received a settlement from the church in 2001, a lawsuit that excluded his sister because of New York’s statute of limitations policies at the time.

Kennington, who was ordained in 1959, played strip poker with 13-year-old Bridget and 8-year-old Brendan to the point of nakedness, he admitted during a court deposition for a suit settled in 2001. After convincing the children the abuse was “our secret,” he gave them erotic back massages before tucking them into bed while their mother was home, Newsday reported in 2002.

Georgetown University has not publicly acknowledged Kennington’s work on campus since the allegations were made public in 2002. The university first learned of the allegations against Kennington in a March 1 email from The Hoya.

The Lyons siblings’ single mother regularly enlisted Kennington, now 85, to help with child care in their Manhattan home. The abuse would soon follow the siblings to beaches in the Hamptons and their grandparents’ home in Florida, where Kennington masturbated to pornographic magazines in their presence, according to Brendan Lyons’ testimony, which was released in 2002.

The Lyons children were raised to look up to Kennington, which made grappling with the abuse decades later all the more challenging.

“That was the big thing for me, because priests are supposed to be infallible and perfect,” Bridget Lyons said in a phone interview with The Hoya. “They’re in a control position, and we in our families are raised to trust them.”

Kennington worked in Georgetown’s Woodstock Theological Center between 1981 and 1983, according to the Official Catholic Directory. He is also listed in the OCD as a researcher in the Catholic Information Center, a research facility in downtown Washington, D.C.

The Redemptorist order refused multiple requests for comment regarding Kennington’s work in D.C.

Christine Lyons learned of her children’s abuse years later when her daughter refused to invite Kennington to her high school graduation party in 1989.

With the support of his mother and sister, Brendan Lyons filed a lawsuit against Kennington in 1994. Almost eight years later, the church settled his lawsuit for an undisclosed amount, as well as a nondisclosure clause that applied exclusively to him.

New York’s statutes of limitations, however, barred his sister Bridget Lyons from seeking legal accountability when she came forward at the same time as her brother.

Restrictive statutes of limitations are the biggest legal hurdle survivors of sexual abuse face in court, according to Stacey Benson, an attorney on Bridget Lyons’ legal team. Benson’s firm, Jeff Anderson and Associates, has specialized in defending victims of child sexual abuse for over 30 years.

“The vast majority of survivors don’t come forward if at all until they are much older,” Benson said in a phone interview with The Hoya. “The majority of laws which were written put such a short time limit that when a survivor is ready to come forward, their legal opportunity is often gone.”

Determined to speak out, Bridget Lyons and her mother shared their story with the New York Post in 2002. That year’s March 21 front page featured a photograph of Kennington with the two survivors of his abuse.

Despite the press attention and settled lawsuit against him, Kennington remains active in the Redemptorist order and currently lives in a private residence for Redemptorist priests in Brooklyn, N.Y. The religious order celebrated Kennington’s 50th anniversary as a priest in 2009, according to Redemptorist order materials archived on Bishop Accountability, a website dedicated to aggregating information about sexual abusers in the clergy.

Approximately seven priests currently live in the residence, which functions as the headquarters for the Redemptorist order in New York, according to an employee of the residence. Priests can conduct services at local congregations, take part in retreats and engage with the community.

Now 47, living in Atlanta and working in violence prevention for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Bridget Lyons is seeking legal justice and accountability against her abuser, decades after she first came forward about Kennington’s abuse.

On Feb. 14, New York passed the Child Victims Act, enabling survivors of sexual assault, including survivors of clergy sex abuse, to bring a civil lawsuit until they reach the age of 55. Before this act passed, New York enforced one of the most oppressive statutes of limitations for survivors, who had only three years to report their assault under the policy, Benson said. That same day, Bridget Lyons and four other plaintiffs, all of whom have alleged abuse by religious order priests in New York, filed a lawsuit against the Catholic Conference of Major Superiors of Men, an umbrella organization that has representatives from all 120 orders of the Catholic Church.

The lawsuit aims to pressure all Catholic orders to disclose which clergy have been accused of sexual abuse. Of the 120 Catholic orders, only six have published such lists, including the Jesuit order and excluding Kennington’s order, the Redemptorists, Benson said.

Unlike Catholic archdioceses, which cover particular geographic regions and face public pressure to investigate and disclose lists of known abusers, religious orders have autonomy that has allowed them to cover up clerical abuse for decades, according to Benson.

“The religious orders have largely gotten away with everything unscathed,” Benson said. “They aren’t releasing names; they aren’t under fire; you do not see headlines about the provincials and the orders. You see the archbishop and the diocese. When in reality, it’s the same thing; it’s just a different group within the church. Especially in New York, every survivor deserves justice, not just a select few that the diocese decide deserve it.”

Bridget Lyons remains hopeful the new act could implement more widespread support for survivors seeking justice.

“I am just hoping that this will also cause a shift where changes are finally made to protect kids,” she said.

Seventeen years after Brendan Lyons received a settlement from the church for his abuse, Georgetown has not acknowledged its ties to Kennington.

Georgetown, along with other Catholic higher education institutions, can play an influential role in supporting survivors of clergy sexual abuse and demanding transparency, according to Bridget Lyons.

“I think Georgetown and Notre Dame especially are very well-respected institutions worldwide,” she said. “If they are sending out a message that accountability needs to be done and if they had a zero-tolerance policy that supported victims, that would be huge.”

If you would like to share any information regarding this investigation, please contact The Hoya at [email protected] or through any methods described here. Campus, local and national resources for processing this content can be found here.

This article has been updated to correctly reflect the location of Woodstock Theological Center from Kennington’s time working there.