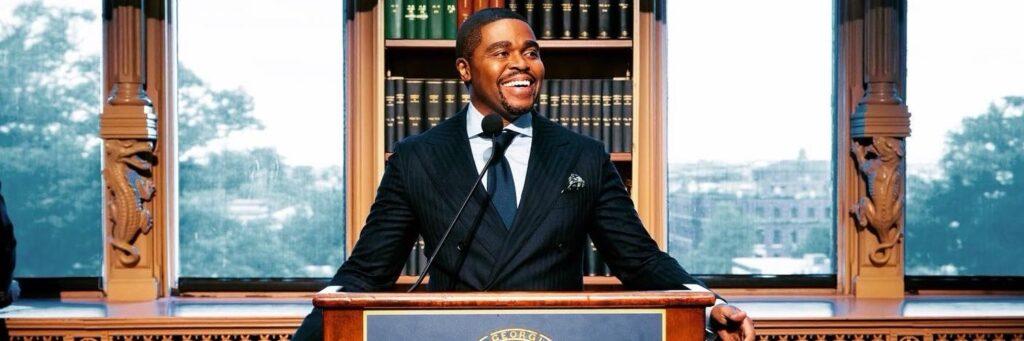

Leading a new school of health amid a global health crisis is no small feat. But Christopher J. King, who will serve as the inaugural dean for the newly launched Georgetown University School of Health (SOH), hopes to serve to the best of his abilities.

Having served as the chair of the department of health systems administration at the Georgetown School of Nursing and Health Studies (NHS), King has entered his new role with a vision of medical excellence and social justice. Georgetown split what was the former NHS into the SOH and School of Nursing (SON) in July 2022 in an effort to recognize the distinctiveness of the university’s nursing and health studies programs.

The SOH comprises the human science, global health and health management & policy departments with more than 400 students, 28 core faculty and 50 active adjuncts. Although it covers three different pathways, King hopes to unite the SOH under the common cause of recognizing and mitigating health disparities.

“It’s exciting for me to be on this side, where I am helping shape academic experiences and helping to create a culture at the School of Health that will help us think more creatively around what needs to be done to help us recognize root causes for these stark statistics and helping us as a school, whether it’s through our teaching, whether it’s through research, to develop solutions that are sustainable,” King said in an interview with The Hoya. “So that at some point, the gap will close.”

Early Exposure to Health Disparities

Growing up in the rural town of Morganfield, Ky., King witnessed firsthand the causes and consequences of the country’s health care divide.

King said many of his hometown’s community members did not have a college education and struggled financially, stuck in a cycle of financial hardship and lack of education that lay the foundation for negative health outcomes.

“It all boiled down to the fact that when you have limited resources, you do the best you can,” King told The Hoya. “You go to fast food restaurants. You don’t make the healthiest choices because of the restrictions that you have on your life.”

King noted that when he visits his hometown, he is struck by the lack of healthy food options. According to King, fresh spinach and whole-wheat bread are nonexistent at the local Walmart.

King also said he noticed a trend of early deaths in his community, many of which were among his family members.

“It became clear to me that they were dying prematurely for things that could have been prevented: smoking, alcohol, mental health issues that weren’t diagnosed,” King said.

This realization became a stepping stone for King’s exploration of community health, which he pursued in college. After completing his bachelor’s degree in school and community health education at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C., King became a health educator and CPR instructor at Parkdale High School in Riverdale Park, Md., located just outside of Washington, D.C.

King’s experience in CPR training became a gateway to working at Prince George’s Hospital Center, where he was recruited into the education department after independently teaching CPR courses to hospital personnel. There, he also worked in human resources as well as organization leadership and development before moving on to work at Greater Baden Medical Services, Inc. in southern Maryland, which is a federally qualified health center (FQHC). A FQHC provides primary care services to underserved populations and charges for services based on a sliding fee scale that is adjusted based on one’s ability to pay. Therefore, no one is ever turned away from receiving the care they need.

King oversaw numerous programs at Greater Baden Medical Services, including van transportation services and chronic disease programs for those with cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. He also founded a new women, infants and children clinic, in addition to being a lead grant writer.

It was during his time at Greater Baden Medical Services that King said he realized the potential and current pitfalls of the health care delivery system.

“That is when I was really able to see that we can provide really, really good medical care,” King said. “But if people are living in communities that don’t have the infrastructure for healthy living, they are not gonna see significant improvements in the health of those populations.”

In Prince George’s County, there is a lack of primary care providers, behavioral health specialists and providers who accept public insurance, according to the 2016 Prince George’s County Community Health Needs Assessment. This report also found social determinants of health such as poverty level, education level and access to healthy food and housing are resulting in the county’s poor health outcomes.

King said he has also been able to hear directly from the people affected by health care inequality by doing community needs health assessments, which helps inform institutions about the health issues and gaps in health care, in Prince George’s County for MedStar Health in Columbia, Md.

Fighting the Health Care Gap

For King, there are two main causes of health disparities: a lack of livable wages and a health care delivery system focused on treating symptoms rather than prevention.

“It feels like a gap. It feels to me like, and what people tell me is that it’s very transactional: ‘I go to my doctor when I need X,’ but it is not really a meaningful type of interaction,” King said.

King also said that although a lack of insurance is often the first issue that comes to mind when people think of health care access, it is not an issue that can be solved in isolation.

“We cannot just think that just because you have insurance, everything is going to be well,” he said. “People have insurance, but they are still not engaging in medical care.”

While at Greater Baden Medical Services, King took action to mitigate these disparities in underserved populations by securing a Bilingual/Bicultural Demonstration grant for Greater Baden Medical Services from the Office of Minority Health in 2007. He used the grant to implement the National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards, which emphasize the importance of providing care to people from diverse backgrounds and improving health literacy in immigrant, migrant worker and Spanish-speaking populations.

However, King said he would not have been successful in securing this grant without having read “Unequal Treatment,” a book written by a team of medical experts detailing the ways an individual’s social circumstances, when paired with racial and ethnic disparities, limit one’s access to health care. For King, “Unequal Treatment” gave him a deeper understanding of the critical role bias plays in the U.S. health care system.

“People come to work, and they want to really do the right thing,” King said. “But we are living in a world, a society that has all these different messages. And we make decisions when we just look at a person.”

King found further insight into the health care system from another book, “Medical Apartheid,” which brings attention to how mistrust in the health care system originates from decades of abusing Black people’s bodies under the guise of research.

King said it is important to view modern challenges with equal access to health care as a product of centuries of history.

“My work is also around making sure that we acknowledge our history and the harm and using that knowledge to make change. I call it atonement,” King said. “How do we create new practices and policies with an atonement lens?”

For King, this lens of atonement will be crucial for the SOH’s mission and work.

“As an academic institution, our responsibility is also to make sure that our students understand and reflect on our history,” King said. “Because through that knowledge, I think they will be much more impactful in their work and just their own lives.”

A Vision for the School of Health

Equipping students with the means to make an impact is one of King’s main goals as dean of the SOH.

King said he plans to achieve this goal through working with local nonprofits to facilitate opportunities for students to engage with the D.C. community rather than staying within the academic bubble of Georgetown.

“My vision for the School of Health is for us to be a world-class academic destination for advancing health, with a specific focus on populations that have been historically marginalized or disenfranchised,” King said.

This focus on addressing health disparities in the local D.C. community was a priority during the summer 2022 selection process for King’s role, according to Dr. Edward B. Healton, who was involved in the process of hiring King and currently serves as the executive vice president for health sciences and executive dean of the Georgetown University School of Medicine.

“People are oddly sometimes more aware of the health disparities that are in poor and underserved communities across the globe and are less aware that a mile away, we have the same problem,” Healton told The Hoya. “So, Christopher has been very aware of that and focused, as are others at Georgetown, but he certainly is.”

John Monahan, the senior adviser to University President John J. DeGioia (CAS ’79, GRD ’95) and former interim dean of the NHS, worked closely with King during his transition and while King was chair of the department of health policy and management.

Monahan said he admires King’s commitment to mitigating the intertwined crises of health and racial disparities closer to home.

“I have had the privilege of knowing Dr. King for several years as a scholar focused on racial disparities, and I especially admire his work examining the role of historical structural racism in shaping health outcomes in our own city of Washington, DC,” Monahan wrote in an email to The Hoya.

Amid the health divide, King said the SOH has the potential to be a part of the movement for creating a society where everybody can make well-informed decisions about their health. The students of the SOH will be one part of fulfilling this mission.

“We need to be sure that we are mirroring as much as possible the real world so that when our students go out and do wonderful things in the world, they’re able to effectively communicate and navigate people who have very different narratives in a constructive way,” King said.

To realize the mission, a task force co-chaired by King and David M. Edelstein, the vice dean of faculty in the Georgetown College of Arts & Sciences, is creating a blueprint for the SOH that includes community engagement opportunities, research focuses and curriculum content that will be submitted to university leadership at the end of this academic year.

Edelstein said King’s dedication to his core values has served as a constant reminder of what the SOH should strive to achieve.

“I think of racial justice and health equity rights as really being two of those principle commitments that he has,” Edelstein told The Hoya. “He has made sure in our work that we never forget. And we never forget the importance of that to the mission of any School of Health that’s going to be affiliated with Georgetown and what we collectively want to accomplish.”

A Personal Commitment

King said his work can be challenging because of the emotional toll of grappling with difficult and pressing issues on a daily basis.

“A lot of my work is around race and systemic racism and helping everyone, even myself,” King said. “Everyone realizes that it’s real, and it’s what happens. It’s not just impacting that one person or that one population; the whole society is impacted by it.”

His role as SOH dean will allow him to respond to these inequities in a tangible, impactful manner, according to King.

“How do I, as a Black male at Georgetown, as a dean, use my voice in the most constructive way to raise the bar for all of us, for faculty, for students, for staff? That’s been a challenge, but it’s a challenge that I am prepared to undergo and continue to undergo, frankly, for the rest of my life, because I know it’s important work,” King said.

King said he tries to emulate former U.S. President Barack Obama, whom he regards as a role model, when dealing with difficult situations.

“What inspires me about him and his leadership, is his ability to always maintain his composure, when the storm is occurring and people are doing and saying things that can really, really ruffle someone’s feathers. This is a person who always is really even keel. I think that is a superpower. It is truly a superpower,” King said.

King has found further inspiration from his grandparents, whom he said have been his true mentors throughout his career.

“They really, since I was a child, just really inculcated in me the importance of doing the right thing, and following your heart, following your passion and everything else will follow,” King said. “And that’s always been my North Star.”

Using his grandparents to guide him in his new role of dean, King said that he sees developing the new SOH using all the available resources and expertise at Georgetown as an opportunity to impact health care on all levels.

“How do we pull all this together in a meaningful way so that we’re much more impactful, whether it’s locally, nationally or globally? That’s been a big takeaway for us. We really have a lot going on at Georgetown. Everyone’s doing something that focuses on health. How do we pull it together?” King said. “It’s a challenge, but it’s an opportunity.”