When the United States elected a Black man to be president in 2008 and again in 2012, much of the world rejoiced. Abraham Lincoln had abolished slavery. Martin Luther King Jr. fought for civil equality. Now, Barack Obama was going to make the United States post-racial, and there was finally true potential for the nation to finally become “color-blind.” One of the biggest proponents of this sentiment was Hollywood. With a distinctly non-white experience inhabiting the world’s most powerful political office came a movement to change Hollywood into a more politically conscious force. This reckoning of a post-racial United States spanned from erasing Disney’s racist history to the removal of “Gone With the Wind” from the HBO Max catalog.

However, the most enduring legacy of post-racialism emerged in the practice of race-bending. In a subversion of Hollywood’s affinity toward “whitewashing” characters, that is, portraying traditional characters of color as white, creators began to reimagine historically white characters, from superhero movies to Disney princesses. Seen as far back as Rodger and Hammerstein’s “Cinderella” in 1997, race-bending remakes have drawn both criticism and acclaim. Love it or hate it, one cannot deny they are here to stay. There are many examples, from Thomas Jefferson in “Hamilton” to Annabeth Chase in the Percy Jackson television series, but none are perhaps as memorable as the Sharma family in “Bridgerton.”

“Bridgerton” made race-bending sexy, fun and escapist. Historically fetishized or de-sexed communities, such as Black women or plus-sized characters, saw themselves as sexually empowered and liberated. With Shonda Rimes’ signature “color-blind” casting, a story hinging on a Regency-era society was freed from the horrors of colonialism and slavery, “Bridgerton” allowed people of color to see themselves on screen without being weighed down by the horrors of racism.

However, as Vox highlights, the show exists not in a completely fictional world, but an almost fictional one, where real historical figures like Queen Charlotte (interpreted as Black) mingle with your favorite debauched fictional family. “Bridgerton” toes a dangerous line between alternate and revisionist history, a move Screenwriter Chris Van Dusen stated is intentional and integral to the show’s message. The creators of “Bridgerton” took up the mantle of representation in a politically fraught moment of history and strove to deliver the social commentary prominent in other influential works from writers like Jane Austen or the Brontë sisters. With this quest, “Bridgerton” becomes vulnerable to the question of representation.

Much has been said about the show’s problematic portrayal of the Black experience and its historical revisionism. Even more has been said about the problems of race-bending overall, such as enforcing racial stereotypes rather than furthering a space for Black and Latino actors to create and showcase their own stories. However, I feel little has been said about South Asians in relation to this conversation, even with the context of South Asian “race-bending” media such as “Velma” (2023), the “Mean Girls” musical remake’s casting of Avantika Vandanapu as Karen or, as discussed in this article, Kathani “Kate” Sharma in season two of “Bridgerton.”

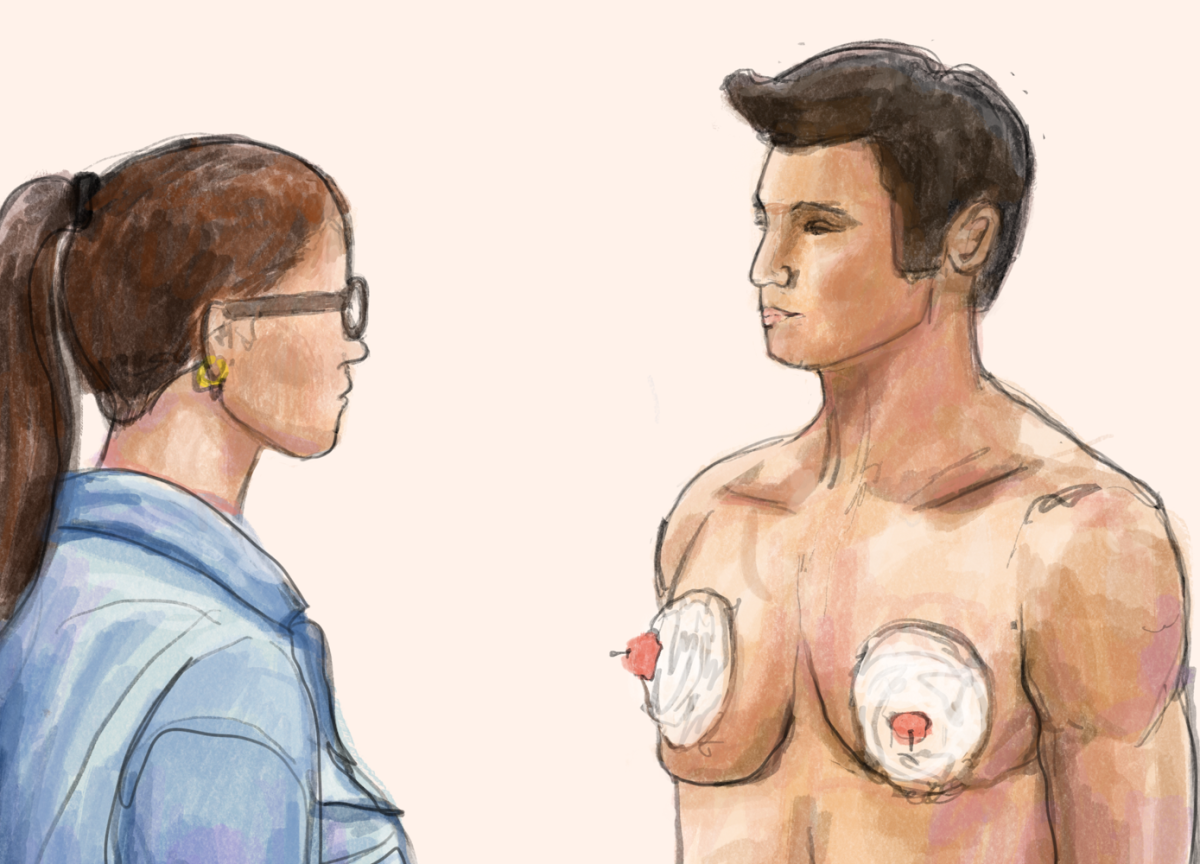

Sharma is meant to represent the eponymous eldest daughter of the South Asian family: shouldering all the responsibility yet receiving none of the rewards. However, her South Asian heritage only extends to the color of her skin, with poor research underscoring her character. In the show, Kate is called “didi,” the Hindi term for “sister,” yet she uses the Bengali “bon” for her younger sister. Furthermore, she refers to her father as “appa,” the Tamil word for “father,” but is said to speak Marathi. Moreover, the anglicization of Sharma and her sister’s names is never addressed, despite such practices being a deep-rooted feature of identity loss for many in the South Asian diaspora. Even more confusing is the inclusion of the Haldi ceremony in her sister’s wedding when not all states, particularly those in South India, celebrate it.

These instances highlight the ignorance that defines Sharma’s character, turning her South Asian identity into a vehicle for white audiences to feel “cultured” rather than an authentic representation — one that accounts for the diversity of South Asia in language, region and tradition. Through this example, a core argument against race-bending emerges: by erasing the cultural specificities of race altogether, “Bridgerton” overlooks not only the trauma of racism but also the joy of existing in a society that honors your roots and culture. In a sense, by only hinting at race in order to depoliticize media, Hollywood productions absolve the system of responsibility and erase even the positive lived experiences of racialized characters. Sharma’s character reinforces Western culture and Christian civilization as the norm while reinforcing other cultures as anomalies that should not be discussed openly so as to avoid discomforting Western viewers.

Whatever the loss or gain, the reality is that we all exist in a world where race matters. Instead of trying to bury this fact, Hollywood must reckon with it and stop erasing identity, whether good or bad. The ideal of post-racial Hollywood only serves to harm the people it supposedly strives to help.