In the song “Don’t Look Back in Anger,” Oasis sings: “And so, Sally can wait / She knows it’s too late as we’re walkin’ on by.” I can’t help but relate to Sally.

So, Ryan can wait; I knew it was too late when I saw the queue number 97,224 on Ticketmaster. In front of my laptop at 3 a.m. on Aug. 31, I saw my chances to witness the dramatic reunion of the greatest ’90s Britpop band — sorry not sorry, Blur fans — slide away.

But this story isn’t about my inability to secure tickets on the Oasis Live ’25 tour. Rather, it’s about what Oasis means to me and millions of other fans –– nostalgia, poetic hedonism, bleak positivity –– and how Ticketmaster undermined, for me, the band’s cultural iconography.

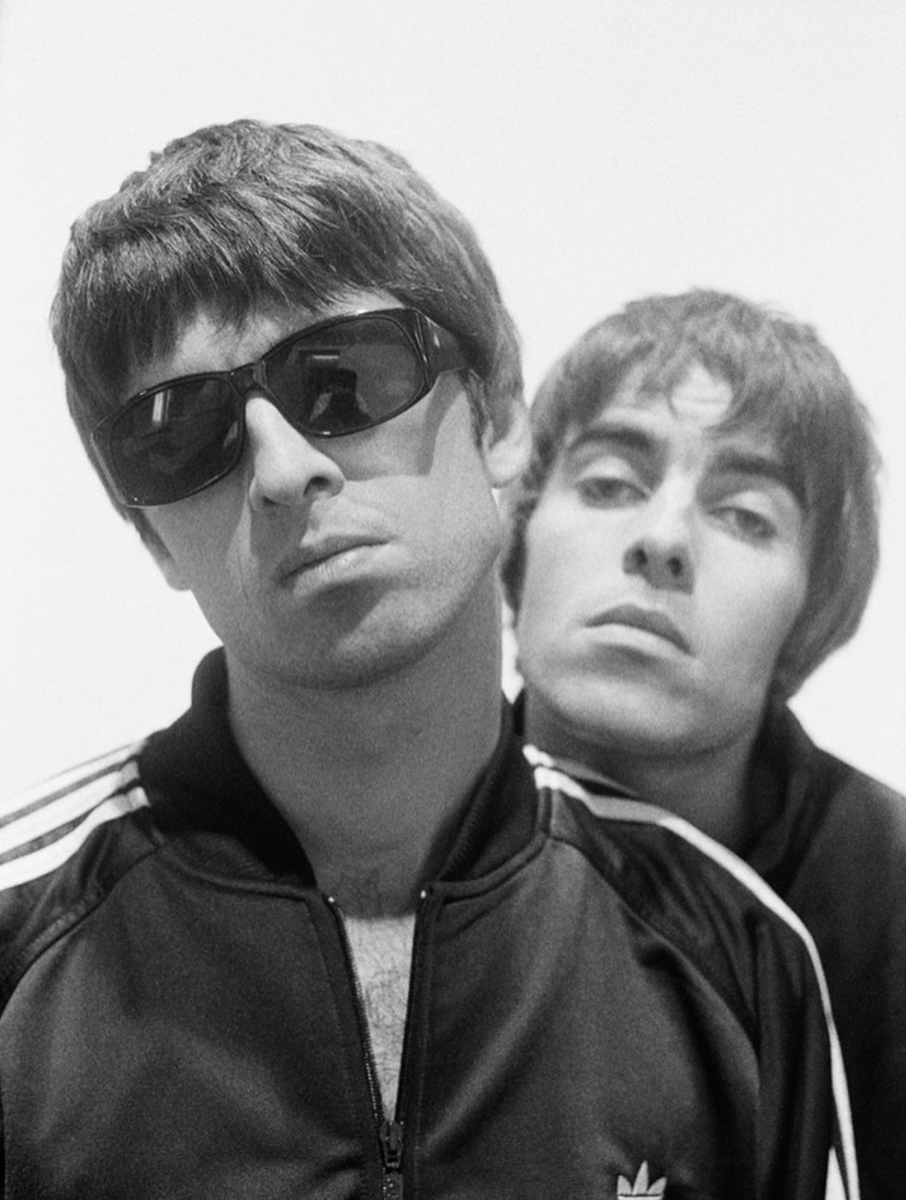

From the beginning, Oasis was a turbulent and strife-laden band. Liam and Noel Gallagher — the brothers who form the core of the band — grew up in Manchester, U.K., born into poverty and a family “wrapped up in violence and drunkenness,” as Noel told Esquire. Liam is very open about the domestic violence that was rampant in the house until his mother left, taking him and his brothers with her.

As the band achieved commercial success –– with their debut album “Definitely Maybe” and sophomore album “(What’s the Story) Morning Glory?” –– the brothers literally rode the high: alcohol, drugs and even politics surrounded their newfound hedonistic lifestyle. But the band’s kryptonite would be the brothers’ interpersonal feuds, with public fights and vulgar insults leading to the band’s separation in 2009.

But there’s more to Oasis than their widely publicized drama in the timing of their ascent. Oasis emerged as the social fabric of the U.K. started to change in the ’90s, captivating audiences as the country underwent stark political shifts from Conservative Thatcherism to the hope offered by Tony Blair’s New Labour. The band’s lyrics and origins seemed to strike a chord that harmonized perfectly with its moment in time.

Liam continuously points to “Live Forever” in “Definitely Maybe” as his favorite Oasis song. Written by Noel in 1991 before he joined the band, “Live Forever” tells of a vision to reach a higher status, whether as a person or as a band: “Maybe I just wanna fly / Wanna live, I don’t wanna die.” Placed in stark contrast with the brothers’ dark childhoods, the lyrics’ bleak optimism hidden behind a rock ’n’ roll melody captures the essence of British workers at the time: undergoing high unemployment and deindustrialization as the social issues of Thatcherism emerged en masse.

The song then hints at this sense of camaraderie among the common man, singing, “I think you’re the same as me / We see things they’ll never see / You and I are gonna live forever.” To me, this song is why millions of working-class Britons subscribe to Oasis despite the lavish lives the Gallaghers lived in the ’90s.

“In England, 90% of the working class’ favorite band is Oasis,” says Anthon Ryan, 27, a friend of mine from London. “They’re like a religion over there, especially up in Manchester.”

Anthon continues: “They just fit my personality really well. I remember once I was in a pub and the guitarist started doing an Oasis song. This girl from New Zealand asked me, ‘Is every British person’s favorite band Oasis?’ These two guys I’d never met and myself at the same time just said ‘yes.’”

So, when I think back to my ticketing experience for Oasis, I am angry. Though I am neither a Brit nor a member of the ’90s working class, Oasis was undeniably an icon of that era — representing a generation facing unique challenges of their time.

That same generation sat in front of their laptops waiting on Ticketmaster and its affiliated links, as instructed — Oasis had explicitly stated that the resale of tickets outside of Ticketmaster and its associated websites would not be tolerated, potentially resulting in cancellation.

But, as soon as ticket sales went live, many fans saw thousands of tickets appear on resale websites like StubHub, and even Ticketmaster appeared to raise prices on their own as demand exploded –– listing prices that differed from what the band had promised.

Ticketmaster may be a quantitatively efficient venue for ticket sales, but qualitatively, these companies continuously fail to distribute tickets to the right fans. The working-class audience from the ’90s that saved up to see their favorite band, only for their chances to be snatched away by massive ticketing giants –– those are the people who I empathize with. The anger and agony of the fans, the integrity of the artists and the inherent quality of the concert experience –– that is what is swept under the rug.

I have no doubt that Liam and Noel sing their lyrics with the same passion as they did in the ’90s. But as Ticketmaster forces Oasis tickets to price out the average fan, I fear that the hope Oasis used to offer the working class is slowly sliding away.

LA • Sep 19, 2024 at 1:29 am

I listened to Oasis non-stop in my Village B dorm room in 1995 and onwards through graduation. It was the soundtrack to nights out on M & Wisconsin. Their early tunes, and Gtown, and forever linked in my mind.