As I graduate this semester with a degree in economics, I’m still having trouble figuring out what exactly I’ve learned in those countless lectures filled with supply-and-demand graphs and equations. By no stretch can I call myself an economist — yet, as I reflect on my coursework at Georgetown, I have come to realize that economics is less about learning models and theories and more about bringing a new and rigorous perspective to everyday life. There are so many instances where we can approach ideas and concepts from an economics state of mind. Take, for example, something near and dear to a lot of us: hookup culture.

As I graduate this semester with a degree in economics, I’m still having trouble figuring out what exactly I’ve learned in those countless lectures filled with supply-and-demand graphs and equations. By no stretch can I call myself an economist — yet, as I reflect on my coursework at Georgetown, I have come to realize that economics is less about learning models and theories and more about bringing a new and rigorous perspective to everyday life. There are so many instances where we can approach ideas and concepts from an economics state of mind. Take, for example, something near and dear to a lot of us: hookup culture.

In this simple model, we have two actors — I refrain from assigning genders or sexual orientations to either one — who are in a situation where they encounter each other after recently hooking up. Each player now has two options: They can either a) pursue the other person by starting up a conversation or b) brush off the incident as if nothing happened.

We are also going to make some assumptions. There is no history — this is the first time they have hooked up. Each person does not know if the other person is interested.

Pursuing the other person is contingent on that actor actually being interested in the other person. Therefore, if one person is not interested in the other, that actor will not pursue. These two players go to a small school like Georgetown, where there is a high likelihood of seeing the other person again in public.

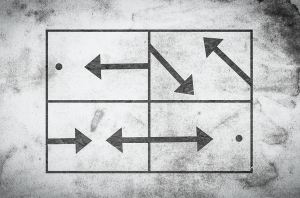

In creating the game, we essentially have four possible outcomes: a) both pursue each other, b) both ignore each other, c) one pursues and the other doesn’t and d) vice versa. If both pursue, the implication is that both are interested in each other, which makes this most optimal outcome — again, only if both are interested. If the two end up not pursuing each other, there is no harm done. However, if one pursues and the other doesn’t, it is personally embarrassing for the one who pursues upon rejection.

If each person knew what the other wanted, we would always have two possible outcomes, termed “Nash Equilibria:” Either both pursue or both don’t pursue. These outcomes are bolded in the table above. If you recall your introductory economics or international relations classes, the situation we have here is very similar to the classic “stag hunt” game.

However, an important distinction is that the actors make their decisions based on what they perceive the other person’s preferences to be. Therefore, even if one person is interested in the other, that person’s perception of the other’s disinterest will cause that person not to puruse the other.As a result, there are situations where two actors who like each other would be better off if they had chosen to “cooperate,” but instead, they both end up choosing to “defect” because they are unsure of what the other person thinks. At the same time, there is the very real outcome of taking the chance and pursuing someone but being rejected because that person does not reciprocate interest.

How often will these “sub-optimal” outcomes occur? It depends on how people generally perceive each other. In a school where there is already a preconceived notion of hookup culture, individuals go in with the automatic assumption that everyone is out there just for a good time. Additionally, unsuccessful first iterations of a game, i.e. getting rejected, can further incline people to take fewer risks in later iterations and make defection their automatic strategy. Finally, at a small school like Georgetown, there is the added factor of constantly seeing familiar faces on campus. This even further disincentivizes people from pursuing the other person in fear of potential social awkwardness as a result of rejection.

What are the takeaways from this? The first is how distorted perceptions of other people can end up further perpetuating hookup culture. When we mistakenly assume that everyone else is only interested in hooking up, we automatically become risk-averse and much less willing to take interest in the other person. In reality, the situation may not be so dire: A recent survey by the American Psychological Association found that 63 percent of college men and 83 percent of college women said they would prefer a traditional relationship to hooking up. The misperception that no one wants to date only reinforces stereotypes of hookup culture.

Second, as I demonstrate in my model, there isn’t a high risk to pursuing someone. The worst-case scenario is that you are rejected and you have to deal with some social ramifications. However, if we assume the payoffs I assigned above, it’s probably worth it to take the risk. Given that more people are willing to date than we think, our expected returns on pursuing may not be all that bad.

As someone who is about to graduate this May, I can personally speak about how misperceptions of hookup culture warp the way we view others. So my leaving advice is this: Take the chance. For the lack of a more elegant explanation, your expected return is still pretty good.

Anirudha Vaddadi is a senior in the School of Foreign Service.

Kevin Chen • Oct 12, 2017 at 3:35 pm

I’m not sure the author actually knows what they’re talking about. #Unsubscribe.