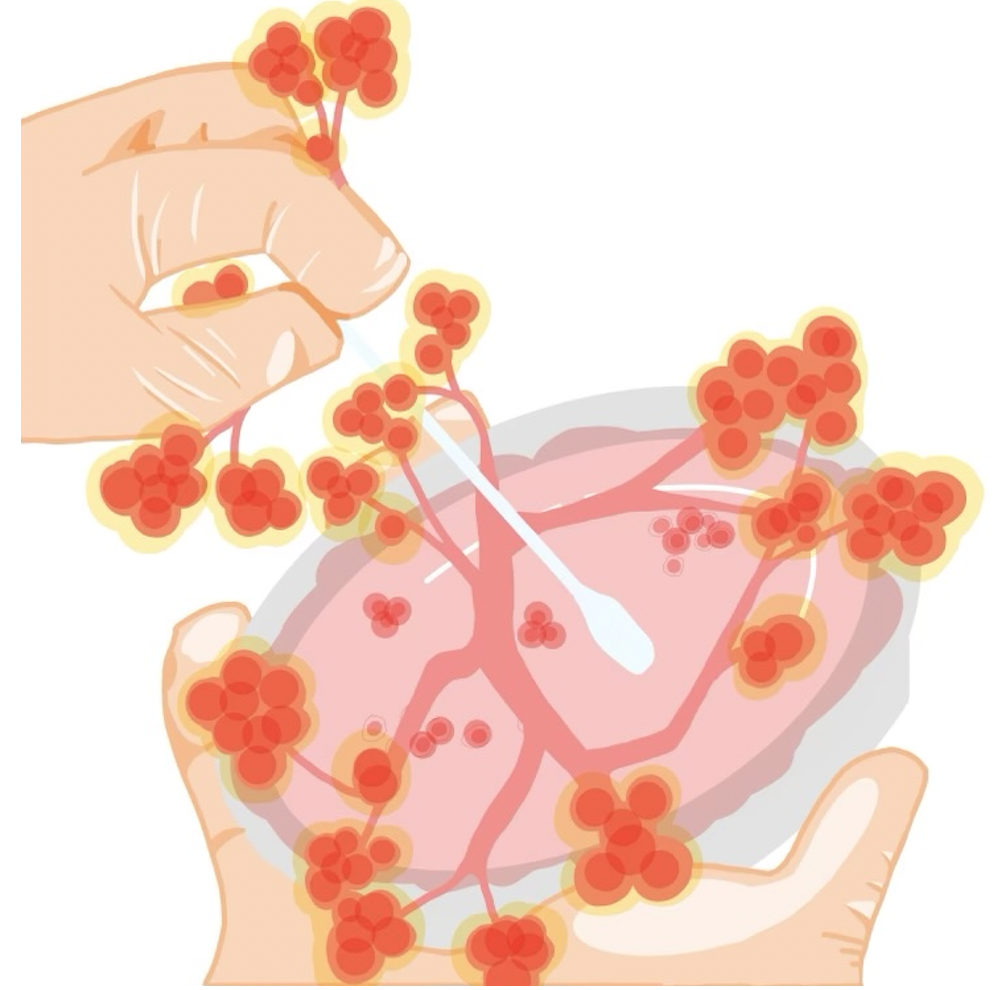

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared March 20 that Candida auris, a deadly fungus, is now an urgent threat to U.S. healthcare facilities, where it can transmit easily from patient to patient.

C. auris has spread rapidly across the nation’s healthcare systems and can acquire resistance to antifungal drugs by inheriting new genes or accumulating DNA mutations.

The CDC reported that from 2020 to 2021, infections of C. auris almost tripled, surging from 1,471 to 4,041 cases nationwide. The organism’s resistance to common antifungal drugs means that C. auris is alarmingly deadly: despite the low case rate, the mortality rate for the fungus is 30-60%.

Dr. Jesse Goodman, an infectious disease specialist at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, explained that in some cases, C. auris only responds to a handful of antifungal drug types, severely limiting the ability of healthcare providers to treat C. auris infections.

“The big problem for anybody who gets infected with this is that there is a fair amount of resistance to the drugs that are used to treat it,” Goodman told The Hoya. “There have been a couple of outbreaks of Candida auris that is essentially resistant to all available treatments.”

In 2021, the CDC reported one cluster of antifungal-resistant cases of C. auris in Washington, D.C., located in a long-term care facility for acutely ill patients.

Ronda Rolfes, an instructor in the biology department at Georgetown, stressed that C. auris is a major concern for patients in these types of healthcare settings — where the fungus persists on unsanitized surfaces and human skin — but it is not a danger to the general public.

“In a hospital, it’s surviving on beds and on medical devices,” Rolfes said. “It’s not so much out in the general world, but it’s really high in hospitals and nursing homes, places where patients are immunocompromised or extremely sick.”

Scientists are not sure what causes high levels of antifungal resistance in C. auris, and researchers are similarly unsure of the pathogen’s origins.

Dr. Dongmei Li, a research assistant professor in the department of microbiology and immunology at Georgetown University Medical Center, says that global warming and excessive antifungal use in agricultural settings are two factors that may have enabled C. auris — which appeared in the U.S. in 2016 — to evolve into such a life-threatening human pathogen. If a fungus is exposed to excessive amounts of antifungals, strains with random mutations that confer drug resistance can proliferate, promoting antifungal resistance in species like C. auris.

“The likely reasons are selection due to global warming and the use of azoles, which are the most common antifungal drugs in clinical settings,” Li told The Hoya. “They’re also used as a fungicide, to kill fungi that are damaging plants in an agricultural setting, where they spray lots of azoles into the environment.”

Li explained that climate change may have made it easier for nonpathogenic strains of C. auris from the environment to become pathogenic in humans, where temperatures are typically too warm for other fungi to colonize the body.

“There is a theory that global warming basically helps it adapt to the host,” Li said. “This fungus has gotten a mutation due to temperature changes in the environment, and now, it can tolerate higher temperatures in the environment and the host.”

The heat-tolerant and antifungal-resistant evolution of C. auris means that clinicians need new antifungal drugs to effectively target the pathogen. However, according to Goodman, pharmaceutical companies don’t see antifungals as highly profitable, which has slowed drug development.

Goodman said healthcare facilities must employ stricter sanitation measures to slow the spread of C. auris as scientists test newer antifungals.

“It requires really fastidious cleaning — what we call infection prevention and control practices like handwashing, environmental cleaning, and gloving,” Goodman said. “It needs this multi-pronged attack, including better drugs, better infection prevention and the monetary incentives for both.”

Li also stressed our healthcare system’s lack of preparedness to fight other severe fungal outbreaks, beyond C. auris.

“I think that C. auris is the first lesson we learn. In the future, if other sorts of pathogenic fungi appear in the future, it will not be surprising, and we are absolutely not ready for that.”