On the evening of Nov. 8, I sat alone in Car Barn, dejected. My team, Manchester United, had lost once again. I stared blankly at the windowless wall, feeling physically ill.

It was not meant to be this way; we were up 2-0 40 minutes in and cruising our way to an easy victory. We had chances to put the game to bed. The referee screwed us over with a harsh red card. This is what I was telling myself as FC Copenhagen scored in the 83rd and 87th minutes to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. I did not even have the energy to get angry.

My mom sent me a text reading, “Your faith as a fan is being tested.” My friend, who is a fan of rival Manchester City, and had been texting me all along to rub salt in the wound, stops his barrage of messages. That is when I knew it was really bad. Despite the awful experience mid-week, compiling on a so-far miserable season, I could not wait for the weekend, when I would get to do it all over again.

To those who are not sports fans, this may all seem ludicrous, but to those who are, this phenomenon probably seems so rudimentary that it goes without saying. There is a simple explanation. I am a fan, an abbreviation of fanatic. The dictionary says that means I am someone “filled with excessive and single-minded zeal,” who has “an obsessive interest in and enthusiasm for something.” In my case, like so many others, this something just happens to be my sports teams.

To the uninitiated, allowing a group of people throwing or kicking a ball around for an hour every weekend to determine your mood for the rest of the week makes no sense at all. The truth is, when framed like that, being a fan sounds rather absurd. But that simply does not scratch the surface of what following a team means.

Aristotle said, “Man is by nature a social animal.” (I bet you didn’t think Greek philosophy would pop up in the Sports section but here we are). We live in families, we learn in classes, we work in teams, we need to be in groups or societies. In doing so, we become part of something bigger than ourselves, which frees us from our individual responsibilities of day-to-day life. We become small parts of a greater, singular whole, fostering intense feelings of belonging and pride.

Of course, there is a strong part of the psyche that wants to be individual, and this action of becoming part of a group is also a way to distance ourselves from other similar groups, such as fans of a rival team. It is a sense of ‘we are us, but we are also not them,’ and having rivals strengthens identity. It entrenches into the fabric of every team that they exist not only to be themselves but explicitly to be everything their rivals are not.

That is why my friend is so insistent on texting me every time United loses, and why I hate the color sky blue for no other reason than that it is my rivals’ color.

By becoming part of the singular crowd that is the team and its fans, they become an extension of the self.

When we use the royal “we,” as I have multiple times in this article already, there becomes literal neurological confusion as to where we stop and the team starts.

UCLA Neuroscientist Marco Iacoboni says that the brain’s mirror neurons underlie fandom by linking the fans’ and players’ brains. Endocrinologists have demonstrated that fans’ hormonal responses can even mirror those of the players competing. Stephen Reysen, professor at Texas A&M said, “Individuals feel that the fan interest (in this case a sports team) is a part of them, so when the team is winning, you feel like you are winning even though you are not a player.”

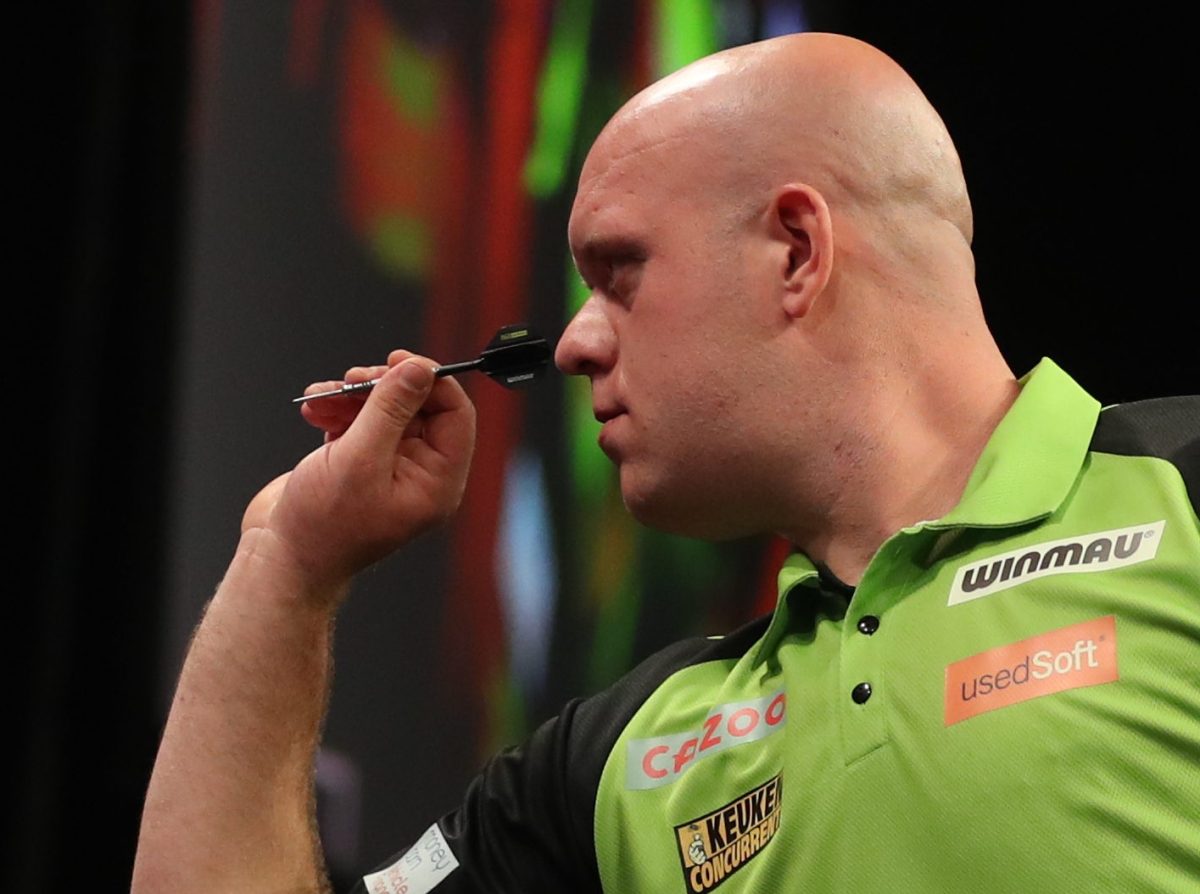

Unsurprisingly, the self-esteem of some fans also rises and falls with a game’s outcome, with losses affecting optimism on all subjects ranging from winning a game of darts to asking someone out.

Sports provide a consistent space where people, especially young men, can express their emotions in a way that is often not seen as culturally appropriate in other settings. I have never experienced raw elation in the way that I did when celebrating a United goal at Old Trafford. I have also never been so livid at anything else as I have been at United.

As we follow our teams through thick and thin, we realize that the results ultimately become irrelevant, despite meaning everything in the moment. For so many of us, watching our team becomes a ritualistic constant in our ever-changing lives. You will always have your team to rely on. Maybe not to win, but to be there for you, to make you feel like you matter, to give you a sense of purpose.

That is why, despite my mom’s claim, I know my faith will never waiver.