In 2017, Visa offered tens of thousands of dollars in assistance to any business willing to partake in its Cashless Challenge and begin refusing to accept cash. This initiative fit broadly into the company’s vision of a Cashless World. As credit card companies, tech moguls, small businesses and even the entire country of Sweden move toward this proclaimed hyperefficient future without cash, some have begun to question just how inclusive this cashless world really is and what its effects on disadvantaged communities in Washington, D.C., will be.

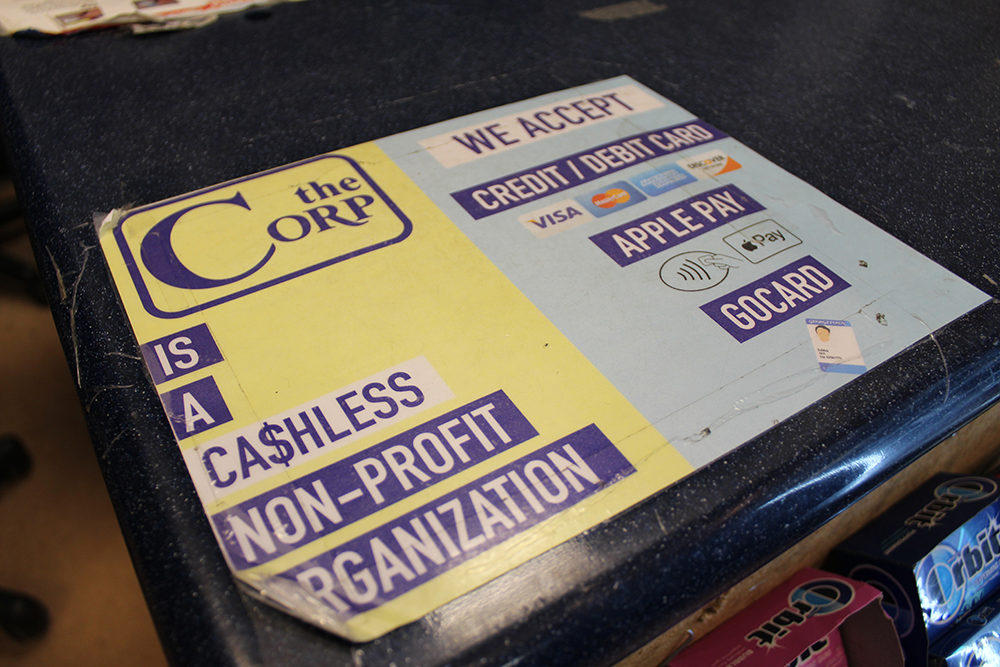

As more businesses begin refusing cash transactions, residents of D.C. find themselves unable to purchase goods from many local shops. Over the last two years, many businesses throughout Georgetown and the District have transitioned entirely to cashless practices, including Students of Georgetown, Inc., commonly referred to as The Corp. Other retailers like Sweetgreen, Barcelona Wine Bar, South Block’s Georgetown location, Surfside in Dupont Circle and Menchie’s on U Street have also cut out cash.

Despite lowering costs for small- and medium-sized businesses, however, operating with exclusively cashless transactions disproportionately disadvantages low-income families, people of color and immigrants without documentation. These historically marginalized groups nationwide go without bank accounts at higher rates, leaving them unable to participate fully in an increasingly cashless economy.

As a result, city and state legislatures, local activists and even the executive branch of the Georgetown University Student Association have begun to push back against the increasingly common cashless practice to ensure all customers are able to live sustainably, regardless of their access to bank accounts.

Increasing Inaccessibility

Critics from across the District have found cashless processes to be discriminatory to low-income individuals and families without access to a credit card. More establishments have begun turning away customers without forms of credit in the District, but students at Georgetown have also felt the effects of these practices on campus.

The Corp adopted a cashless model Feb. 1, 2018. Though The Corp’s storefronts still accept Flex dollars, Students without either a credit or debit card or a meal plan may find themselves unable to purchase from any of The Corp’s seven on-campus storefronts.

As a result, cashless practices make life more difficult for students without credit cards, according to GUSA President Norman Francis Jr. (COL ’20).

“It is an elitist practice that prevents a lot of students, especially low-income students, from living properly on campus by making basic life necessities such as food or cleaning supplies inaccessible,” Francis wrote. “Cashless is classist, plain and simple.”

Cashless businesses should return to accepting cash for the sake of students who cannot or prefer not to use credit cards, Francis wrote on behalf of the GUSA executive.

“Not accepting cash is a direct attack on low income consumers, and we hope cashless businesses reconsider that business practice,” Francis wrote.

Cashless practices not only disproportionately affect low-income students, but also present new obstacles for students without documentation. Certain providers of financial services may be reluctant to serve those without social security numbers, and compounded with difficulties of obtaining government approved IDs, many immigrants without documentation in the United States operate without credit cards.

In the face of these difficulties, the Center for Multicultural Equity and Access’s Undocumented Student Services has identified steps that could enable immigrants without documentation to adjust the changing commercial landscape, according to Arelis Palacios, associate director for Undocumented Student Services for the CMEA.

“Some undocumented students and families may not be eligible for bank accounts in certain states,” Palacios wrote in an email to The Hoya. “But we have located a few local/national bank branches that provide these crucial services to undocumented communities.”

A Legislative Pushback

To address public concern surrounding the growth of cashless retailers, many states and cities are seeking legislative solutions.

Just this year, Gov. Phil Murphy (D-N.J.) signed the state’s cashless prohibition into law March 18, and Mayor James Kenney (D-Pa.) signed the city’s bill Feb. 27 — only a few among the growing list of places to require brick-and-mortar storefronts to accept cash. Massachusetts has even had a cashless ban on the books since 1978.

Two separate bills that would ban cashless retailers have also been introduced in the House of Representatives, both of which still await hearing. New York City and Connecticut also have cashless bans that await approval from local legislatures.

As action against cashless practices picks up nationwide, Washington, D.C. Councilmember David Grosso is attempting to finish an effort he started in early 2018. Grosso introduced the Cashless Retailers Prohibition Act of 2019 in February as a follow up to his earlier attempt, the Cashless Retailers Prohibition Act of 2018.

The act expands on its predecessor to prohibit all retailers, not just those retailers selling food, from discriminating against cash by refusing to accept cash as a form of payment, posting signage that claims cash will not be accepted and charging customers different prices depending on their payment method.

Going cashless disproportionately affects younger and low-income consumers because they are less likely to have the means to pay without cash, as well as customers that use cash for accounting and safety purposes, according to Grosso.

“By denying patrons the ability to use cash as a form of payment, businesses are effectively telling lower-income and young patrons that they are not welcome,” Grosso said in a press release. “Through this bill, we can ensure that all DC residents and visitors can continue to patronize the businesses they choose, while avoiding the potential embarrassment of being denied service simply because they lack a credit card.”

Residents of the District have either no access to bank accounts or significantly limited access to financial services at higher rates than the national average. Of all households in the District, 29.4% had significantly limited access and 8% had no access, according to a 2017 survey from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

In total, over one-third of the Washington, D.C. population have either limited or no access to a bank account and depend on cash transactions, signifying that nearly 40% of D.C. still depend heavily on cash transactions.

Despite the large portion of District residents who rely on cash, Grosso’s bill has been sitting in committee since its introduction in February. Grosso’s previous bill also sat in committee awaiting hearing for over 10 months until the end of the legislative period, causing it to fail.

Gross was unavailable for comment at the time of print.

Though its passage remains uncertain, Francis praised Grosso’s bill, saying it would be beneficial for the Georgetown community.

“If all businesses accepted cash, that would be ideal and it should be the standard,” Francis wrote in an email to The Hoya.

The Future for Cashless Businesses

Despite the obstacles cashless businesses can present to students at Georgetown or consumers in the District, the practice has grown more common because it can help small businesses stay afloat.

Small- and medium-sized businesses nationwide previously have reported paying billions of dollars each year in costs associated with transporting and handling cash, according to a study from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Cashless models eliminate the need to physically transport money to and from the bank and the need to pay employees to count balances through the day.

South Block’s Georgetown location accepted cash as a payment method until 2018. However, as the business opened more storefronts, fewer customers paid in cash, according to founder and CEO Amir Mostafavi. Cash sales plummeted from 40% of all sales in 2011 to 6% before the decision to become cashless.

Cashless transactions have also diminished the likelihood that businesses like South Block will experience robberies, given the reduced amount of cash held in storefronts each day. This factor was a major consideration when the business went cashless, according to Mostafavi.

“We also felt that carrying cash and the safety risks around it were no longer justified due to low cash transactions,” Mostafavi wrote in an email to the Hoya.

The Corp began refusing cash transactions to minimize costs associated with accepting cash, according to CEO and President Seo Young Lee (COL ’21).

Cashless businesses have different plans for handling legislation barring the practice. South Block will not be engaging in any political activity to oppose the bill, according to Mostafavi.

“We always adhere to any requirements that the state, city, county has on businesses, so we will monitor and make adjustments if need be,” Mostafavi wrote.

Corp leadership knows about Grosso’s legislation and the discriminatory implications of refusing to accept cash, but plans to continue its current practices, according to Lee.

“We are cognizant of the limitations to accessibility that our current payment methods pose,” Lee wrote in a statement to The Hoya. “Regardless of the Cashless Retailers Prohibition Act, The Corp’s ability to serve any and all customers on campus is at the forefront of our planning, and it will continue to remain as a priority in our considerations until all limitations are resolved.”

Businesses like Amazon and Sweetgreen, however, in response to the growing backlash against cashless businesses, have reversed course and begun accepting cash again at certain brick-and-mortar stores, preempting legal requirements.

Francis has been in contact with high-ranking members of The Corp on whether its cashless practices fulfill its mission.

“The Corp has a history of working to provide scholarships and many other philanthropic endeavors to the Georgetown community,” Francis wrote. “We are curious to see what the future holds and we hope the Corp continues to be open to moving towards accepting cash again.”

Correction: This article was updated Sept. 27 to reflect that Flex dollars can be obtained through cash deposits.

GoCard User • Sep 27, 2019 at 2:01 pm

This article states that the only way to put money on a GoCard is via a bank account. I’d like to remind readers that the university has machines across campus to load cash into GoCard (one on the 3rd floor of Lauinger library and another in the Leavy Center) – might advertising these more aggressively and encouraging the university to add some more locations mitigate many of the cash issues, at least on the student side?