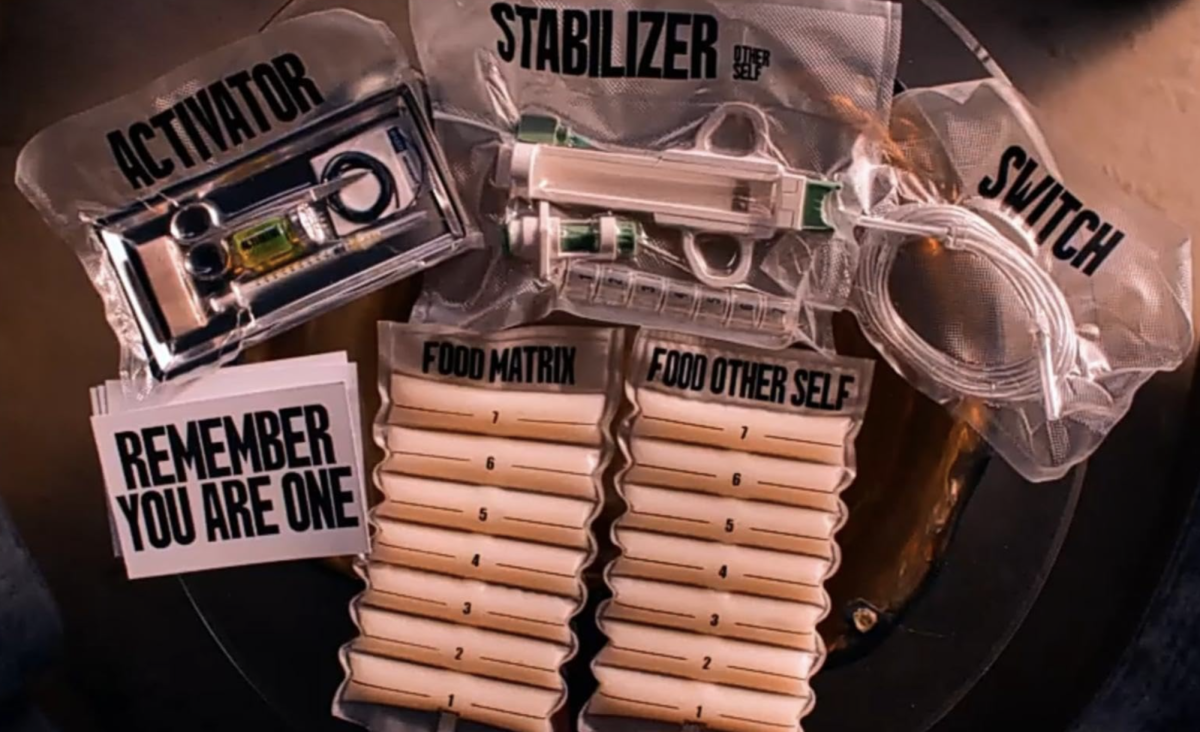

To what lengths would you go to feel the glow of societal validation? Coralie Fargeat’s “The Substance” believes there is no limit to our desperation for approval and succeeds in the public forum, winning the Cannes Film Festival award for best screenplay. When celebrity aerobics show host Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) turns 50, her producer Harvey (Dennis Quaid) delivers a devastating blow, booting her from her own show. Newly purposeless and filled with self-loathing, Elisabeth turns to drastic measures: a mysterious subscription medication, dubbed “the Substance,” that offers its users an enhanced, youthful version of themselves, on the condition that they remember that the two versions of themselves are actually one.

Subtlety and depth are completely forgone in “The Substance,” but Fargeat’s resulting one-note bluntness works. This film explicitly excoriates the internalization of ageism and bodily commodification of women in Hollywood. Little is developed, or even logical, beyond what is necessary for a movie that remains focused solely on its characters’ internal experiences within the system it reprobates. How do the creators of the Substance benefit from the product? How is it possible that Elisabeth Sparkle gained and maintained decades of fame from an aerobics show? These questions are never answered, but this lack of information never impedes the message. However, the lack of subtlety feels belittling to the audience at times — flashbacks to earlier scenes are overused as reminders of the rules of the Substance, and some of the big reveals are so caught up in ensuring audience comprehension that they lose some of their novelty.

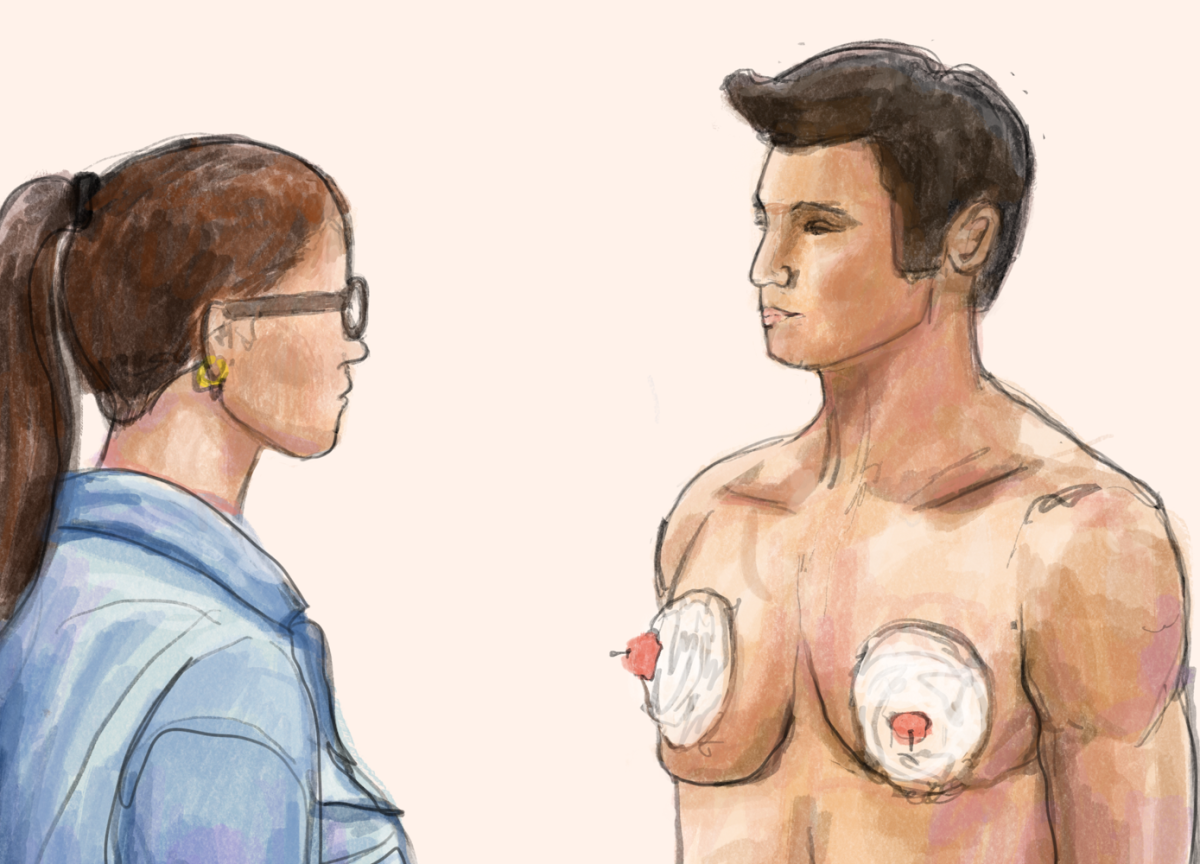

Every choice in the film pervades a sense of discomfort and uneasiness just as in-your-face as the story itself. Extreme close-up shots, Kubrickian looming hallways and tense EDM music alongside the exploitation of every imaginable horror of the human body, including rotting and breaking nails and teeth, injuries of the spine, stitches and needle injections, render the experience truly disturbing. And if the audience’s collective gasps, groans and squirming during the film’s first two hours aren’t enough, the impressive prosthetics in the last 20 minutes are guaranteed to leave the viewer feeling nauseous. Though the last sequence of continuous horrors is certainly exhilarating, the sheer entertainment value comes at the expense of some of the fluency of the central message.

The most heart-wrenching scene in the entire movie avoids this gruesome imagery, instead relying on a raw emotional performance delivered by Moore. As Elisabeth withers away at the hands of her younger counterpart Sue (Margaret Qualley), she agrees to a date in an attempt to resolve her loneliness. However, she is so uncomfortable in her own skin that her preparation drags into hours of continuously returning to the bathroom mirror, unable to accept her body. The poignancy of this scene without the use of body horror begs the question: Was this the best genre to evoke such an important message?

The performances delivered by all three stars are truly exceptional. Moore infuses Elisabeth with a heartbreakingly personal sadness that adds another dimension to the tragedy that ensues. Qualley is sensational in her role as the cunning and greedy Sue, who becomes much more than the vapid pretty girl she is made out to be. The aptly named Harvey is a caricature of the most misogynistic men in the entertainment industry, and Quaid offers an excellent depiction of this sleazy chauvinist in a way that is simultaneously hilarious and terrifying.

Elisabeth and Sue may go to extreme measures, but these measures are rooted in very real attempts for validation resulting from continuously unattainable societal standards. The Substance is just an extreme stand-in for any weight loss drug, botox treatment, diet or other commercially advertised “cure” for whatever bodily feature has gone out of style.

But in its attempt to embrace self-love, the film almost starts to contradict itself. Body horror as a medium for an exploration of ageism unfortunately leads to the idea of the aging female body as gruesome in and of itself. Wrinkles, graying hair, degrading joints and loose skin are villainized, especially as Elisabeth is punished for Sue’s inevitable abuse of the Substance with overexaggerated features of old age and with the interposition of scenes of each woman standing entirely naked in the mirror. Still, this choice works in making the audience complicit in the very obsession with the allure of the young female body that the movie seeks to condemn.

“The Substance” is a grotesquely thrilling experience from start to finish, and though it has little depth to it, its loud critique of society’s fear of aging is resounding. The movie invites us to examine our own internalized standards for the “perfect body” and how that affects our perception of ourselves and others. This topic couldn’t be more pertinent in an age that seems to be defined by social media and constant comparison to unachievable standards. However, squeamish viewers be warned: This movie is not for the weak of stomach.