The issue of safety in sports has recently come to the forefront in the media, and rightfully so. As injuries seem to be occurring more frequently and we learn more about long-term concussion effects, it is reasonable to question what our priorities are not only as fans but also as humans. One part of sports that is so blatantly in contention with some of our societal values is fighting in hockey. The practice of enforcers, fighters, goons – whatever you choose to call them – acting like Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em Robots on skates is so obviously dangerous that it is not legal on the street. So why is it permitted in hockey?

Simply put, and very counterintuitively, fighting in hockey actually makes the game safer.

Conventional safety procedures in sports have often been shown not to work. Think about football; once helmets were introduced, players began using their heads as a weapon. A common sense preventative measure for head injuries today greatly contributes to the concussion issue permeating the sport.

Removing fighting from hockey would function similarly to helmets in football, and the players recognize this. Jarome Iginla, a great scorer of the last decade and current Boston Bruin, recently relayed this sentiment in a Sports Illustrated interview. “Does fighting still have a place in today’s NHL? My answer is a qualified yes,” Iginla said. He continued, “I don’t know of any player who truly loves fighting. Ideally, it would not be a part of the game. But the nature of our sport is such that fighting actually curtails many dirty plays that could result in injuries.”

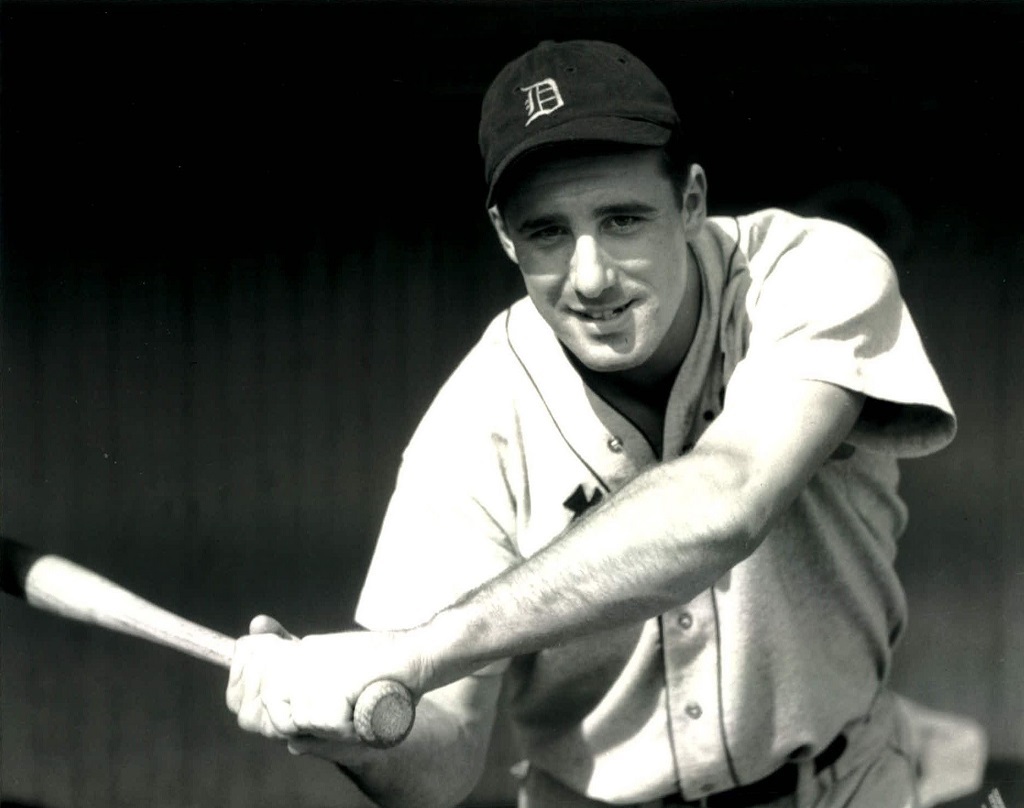

Other players, such as fighting legend Gordie Howe, have shared the same sentiment, and as a result, the NHL owners have refused to budge when the question of banning fighting is raised each year during owners’ meetings.

But explaining just how fighting makes hockey safer requires an investigation into the mentality of hockey players and the nature of the sport itself.

Sticks to the face, lower back, or back of the leg are all viewed as cheap shots and should be called as penalties. Important star players, such as Sidney Crosby, often draw penalty calls much like the stars of the NBA. Unfortunately, referees do not always see these penalties because of the speed of play, and it becomes the job of victims’ teammates to make sure guilty parties engaging in dangerous stick work or who take runs at important players face justice.

Most teams in hockey have what is known as an “enforcer.” Enforcers rarely score, generally possess little stickhandling skills and sometimes cannot even skate that well. Their sole job is to fight players who have broken the unwritten “hockey code” by taking a cheap shot and threatening the safety of other players and the integrity of the sport as a whole.

What I will call the “hockey code” is a unique phenomenon in sports. A general explanation of the code is that personal integrity should be demonstrated because of a collective respect for the game. For example, players will often lose teeth or break a nose and return to play in the same match. They will not take cheap shots targeting the head or back. Flopping, diving or embellishing, which is frequent in basketball, would be unimaginable for a hockey player who abides by the code.

Players know when they have broken the code. They expect enforcers to bring them to their reckoning for doing so. And knowing that a hulking enforcer is going to make you pay is definitely a deterrent for acting in a way to jeopardize playersafety or break the code.

Additionally, fighting in hockey prevents a conflict from escalating. A slash to the back of the knee will not be retaliated by means of a stick to the face, which would perpetuate the issue. Rather, once a fight occurs, the hatchet is buried, and there is a sense of closure to the conflict.

Measures, both by official rules and by the code, have been taken to make fighting in hockey safer. A rule change this year has made it illegal for a player to remove his helmet during a fight. Once players go to the ground, referees immediately break up the fight. And, by the code, more often than not skilled players let enforcers fight in their stead to keep them out of the penalty box and, ultimately, out of the trainers’ room.

Fighting is a valuable tool that diffuses dangerous situations and actually makes the sport of hockey safer. The referees know it, the owners know it, the players know it and you should too.

But it is also a huge part of hockey lore and fanfare. Enforcers gain followings and sell jerseys. Tickets sell out and ratings rise for rivalry games that guarantee physical play and fights. For those who still think fighting doesn’t belong because of the message it teaches: you have a point. Unfortunately, it likely won’t change, so sit back and appreciate that not all good bouts will cost you $60 on HBO pay-per-view.

Matt Castaldo is a junior in the College. FULL CONTACT appears every Friday.