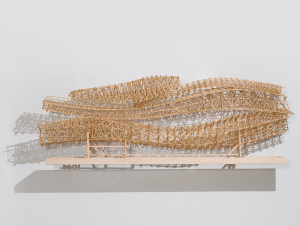

Stephen Talasnik forms an intricate sculpture of geometric designs out of simple material like wood and glue.

Born in Southwest Philadelphia, Stephen Talasnik began experimenting with organic material and geometric designs at a young age. His passion has only intensified over time, and his artwork has developed into a mature and idiosyncratic style. In his exhibit “Linear Transformations, Structures of Questionable Origins,” currently on display at the Marsha Mateyka Gallery, Talasnik manifests his perception of the physical world into a skeletal infrastructure of staggering complexity.

Your site talks a little bit about your creativity as a child. Can you elaborate on the period when you first began experimenting with material and with art?

I was curious enough that drawing and making things were very much easily annexed as a child. I was not interested in academic activity. I used to learn about things by drawing, and I used to invent and make things. As a child, I was always interested in things like the space program, industrial architecture, transportation and the future. What I did as a child really hasn’t left the work I do now. But my work itself is not childlike. It’s the idea that the impulse to make these things is really rooted in a childlike curiosity of how things are made, how things are put together, how things are taken apart: the assembly. It’s an underlying sense of curiosity and invention and harnessing both of those elements that enables me to make the work that I do.

The work grows out of various experiences that I’ve had, but ultimately it’s neither images nor structures grown through nature. I have a responsibility to see what’s out there and pull it through their own individual experience. I’m not interested in making art that reflects nature or mimics architecture. The experiences of one’s lifetime enable the creation of new, innovative types of objects and visual arenas. Ultimately, you’re not just making things that mimic nature but really every experience that you’ve ever had from the time you were a child. Whether it’s the loss of a friendship or the fire in a house or travel to a great place, all of these constitute the creation of an individual encyclopedia, and ultimately you as an artist have a responsibility to create a reaction and form something innovative. The information you cultivate as a child profoundly impacts what you do in a more mature world and an adult life.

The secret is not about imitating what you experienced as a child, but instead accepting that what you learned will become a part of the rest of your life experiences. I’ve been really focused in the past 10 years on public projects, primarily projects on nature. It’s more unusual for me to do an exhibition anymore. The older I get, the more challenged I am by the relationship of nature to architecture. I’m not a naturalist; I grew up in an urban center, and so I’m still intrigued by the relationship of nature to architecture.

What materials do you use in your works?

The sculptural material is generally wood. Although not in this show, I do a lot of work with reeds and things that grow in nature. In this particular show, most of the material is plain wood or wood that is coated with pulverized material, acrylics. It’s easy enough for me to work with material that is simple enough and doesn’t require a lot of technical fabrication. I have a desire to construct without constraint. I don’t use any mathematics to create my sculptures. There’s no software. I use a pencil to draw with and basic wood and glue to build with. They are the most democratic materials and, instinctively, the most intimate and confessional.

How long does it usually take you to complete a sculpture? Can you explain a little bit about the process behind it?

A drawing can take a week or a couple of years. There’s one large drawing in that show (“Propeller”) that took about a year and a half to make, and there are smaller drawings that took even longer. I don’t tend to make things that are easily accomplishable. I tend to work in groups and clusters of ideas, and I work on five to six pieces at a time. It really takes as long as it has to in order to do what I want it to do. The sculpture and drawing reflect a level of devotion to continuation: a summation, a conclusion. For the most part, I’m interested in exploring the range of clues without finalizing the solution.

Is the final image something you conceive before or after you set to work?

It’s rarely ever a pre-conceived notion of what a thing is going to look like. I don’t do preliminary drawings. There are numerous relationships between what I build and draw and aspects of music. There’s repetition and variation that change mildly as a result of human experience. In terms of the building, I function more to the aesthetics. You start out with the basic understanding of a structure and are able to build on that, not necessarily knowing where you are going but knowing what the process involves. I never know what it’s going to look like. I’m invested in the process of building and making. I’m not working with any reliance on a blueprint, and you must have a leap of faith in the end to know when it is complete. My work generally has the air of the unfinished but the complete.

Your current exhibit is titled “Linear Transformations, Structures of Questionable Origins.” What is the underlying story, message or goal of this exhibit?

My work has always addressed fictional engineering. It’s all about the infrastructure of things that are invented, so that there’s always a sense of questionable origin, like where these things are from and how they evolve. They all have a degree of being real, so what I’m doing here is no different than just a continuum of the past 40 years, inventing structures that walk a tightrope between nature and architecture. They are linear structures, skeletal by nature.

I am an interested in engineering. I don’t come from a traditional fine arts background nor do I have formal training in architecture. I draw things I am curious about and that I invented. It’s not the kind of work where you are going to say, “That looks like a tree trunk, an office building.” They have to be enigmatic, a little bit ambiguous of what they are supposed to be in the traditional sense. They rely on language that melds that which is organic from nature and that which is handmade.

Art Piece: Strata

“Strata” is three layers of what appears to be geological levels of plates of the earth. That idea was conceived in a process of what can compare to knitting with wood. Each piece is irregular, and by stacking them, one has to think about how the land has been formed. It looks like reclining skyscrapers.

For me, it talks to the more recent experiences I’ve had in the past four years looking at land formations in the West and how they might be addressed by some guy who grew up in the Northeast. It’s trying to talk about scale horizontally, since I’m a victim of the skyscraper aesthetic. It’s clearly about the land for me but not being nostalgic or sentimental. “Strata” in particular is a nice little summation of the surprises of working out on the plains and pretending to be a cowboy.