The Robert Woods Bliss Collection provides a stunning look into the diverse life of pre-Columbian culture. The exhibit is housed in the more recent add-on to the museum which boasts floor-to-ceiling glass windows and is oriented around a central fountain, and its natural imagery of the ancient works is emphasized by the backdrop of the modern architecture. The cultures represented include the Aztec, Inca, Chavin, Nasca and Chimú. While their religious and social values did indeed overlap in important ways, one can discover small idiosyncrasies that vary from region to region while studying their surviving artifacts. This diversity lends itself to an exhibit of remarkable depth and expertise. Pre-Columbian artisans mastered both stone carving and metallurgy, and their rapid experimentation is exemplified by the range of pieces on display.

The layout and number of items on display make this collection enjoyable and manageable for all levels of art enthusiasts. Just a Wisconsin GUTS bus ride and a short walk away, the Robert Woods Bliss Collection allows visitors to explore an ancient world of myth and craft in less than two hours.

Trophy Head Vessel (Nasca, 350-450 CE)

All humans and animals had a role to play in the layered culture of pre-Columbian societies. The Nascan society from the southern coast of Peru upheld the traditional synthesis of sacred and material beings. The warm yellows and browns of this vessel’s color scheme are deceptively welcoming; in reality, the basin is meant to represent a severed human head. The two lines crossing its lips are cactus spines, and on the reverse side of the pot, a knotted carrying rope is drawn. The face’s red-painted cheekbones place it in the warrior class. Nascan victors often decapitated their war captives and used those heads as an offering to the gods.

All humans and animals had a role to play in the layered culture of pre-Columbian societies. The Nascan society from the southern coast of Peru upheld the traditional synthesis of sacred and material beings. The warm yellows and browns of this vessel’s color scheme are deceptively welcoming; in reality, the basin is meant to represent a severed human head. The two lines crossing its lips are cactus spines, and on the reverse side of the pot, a knotted carrying rope is drawn. The face’s red-painted cheekbones place it in the warrior class. Nascan victors often decapitated their war captives and used those heads as an offering to the gods.

This violent Nascan ritual was much more involved than a simple fight for glory in war. Animals and human heads were connected with the continuous cycle of life, especially of birth and the creation of new life, which was at the core of this settled agrarian people. A row of upside-down hummingbirds crowns the top of the face, connecting it to the ever-renewing process of life and death that transcended simple slaughter on the battlefield.

Standing Male Figurine (Inca, 1450-1549 CE)

The Incas were well-known for their unambiguous, non-figurative imagery. They became expert metallurgists by embracing the metalworking processes brought by craftsmen from the Andean coast. Over time, various compounds were used to increase malleability and enhance certain colors. This piece is a prime example of the more realistic form of Incan art. Although the human is stylized to an extent, its pose and body features retain its recognizably human traits. Its bronze luster and carefully constructed symmetry attest to the skill of Incan artisans.

The Incas were well-known for their unambiguous, non-figurative imagery. They became expert metallurgists by embracing the metalworking processes brought by craftsmen from the Andean coast. Over time, various compounds were used to increase malleability and enhance certain colors. This piece is a prime example of the more realistic form of Incan art. Although the human is stylized to an extent, its pose and body features retain its recognizably human traits. Its bronze luster and carefully constructed symmetry attest to the skill of Incan artisans.

These small figurines held much more importance within Incan society than our modern dolls and action figures; they were used as offerings in Incan shrines. These small objects were also used during a ritual called “Capa Cocha.” This religious practice was centered on human sacrifice, usually of children, in service of the gods. The male figurine would have been buried with the victim to aid in his or her journey to the afterlife.

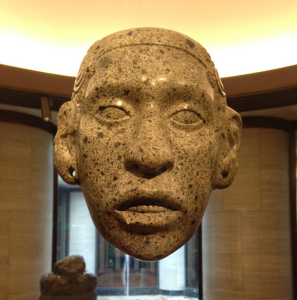

Tezcatlipoca (Aztec, 1200-1520 CE)

Deities often took a human form in the complex Aztec religion. This sculpture shows the imposing face of Tezcatlipoca, one of the central Aztec gods. His wide domain includes the night sky and war. It is even said that Tezcatlipoca invented human sacrifice. His name means “Smoking Mirror.,” and aptly carved into either side of his temples are identical mirrors billowing with smoke. Tezcatlipoca’s main festival was the Toxcatl ceremony, and offerings were made throughout the span of the 260-day Aztec calendar.

Deities often took a human form in the complex Aztec religion. This sculpture shows the imposing face of Tezcatlipoca, one of the central Aztec gods. His wide domain includes the night sky and war. It is even said that Tezcatlipoca invented human sacrifice. His name means “Smoking Mirror.,” and aptly carved into either side of his temples are identical mirrors billowing with smoke. Tezcatlipoca’s main festival was the Toxcatl ceremony, and offerings were made throughout the span of the 260-day Aztec calendar.

Although figures of Tezcatlipoca were often created with obsidian, this particular piece was crafted with greenstone. The Aztecs held intricate cultural and religious ceremonies, and this sculpted mask could have played a primary role in these rituals. While similar stone creations tended to be rather heavy, they were still used as props and masks during these events in order to invoke the spirit of the gods.

Breastplate with Agnathic Feline Face (ChaVON, 400-200 BCE)

The Chavin and Cupisnique cultures were contemporaries of the Olmecs of Mesoamerica. This engraved plate was made long before much of the Aztec and Inca art displayed in the exhibit, but its level of craftsmanship is just as sophisticated. The Chavin fused together the natural and supernatural in a society where everyday people could access the divine realm through elaborate religious rituals. The plate is a pectoral, meaning that it was worn on the chest as a symbol of religious power and social prestige.

The Chavin and Cupisnique cultures were contemporaries of the Olmecs of Mesoamerica. This engraved plate was made long before much of the Aztec and Inca art displayed in the exhibit, but its level of craftsmanship is just as sophisticated. The Chavin fused together the natural and supernatural in a society where everyday people could access the divine realm through elaborate religious rituals. The plate is a pectoral, meaning that it was worn on the chest as a symbol of religious power and social prestige.

The center of the plate depicts a bold feline figure. Two serpents slither from the connected shape of its lower jaw, emphasizing this being’s divine status. Above the feline’s row of gold teeth poke two fangs, which represent a fanged, staffed deity that was central to Chavin religion. Metallurgy was not common practice in this culture, and this beautifully crafted plate was one of the rarer luxuries available to the wealthier class.