In the coming months, the university will open a campus-wide dialogue on its relationship with racism and slavery, which reached its nadir in 1838 when Fr. Thomas Mulledy, S.J., and the Maryland Jesuits sold 272 slaves to a Louisiana planter.

Some might assume that Georgetown’s racial transformation took place in the aftermath. Some might choose 1874, when Fr. Patrick Healy, S.J., became the first black president of the university. Others might choose the 1960s, when substantial numbers of black students began to arrive at Georgetown. Still others would suggest that our racial transformation is ongoing. If I were to select a date, it would be June 10, 1982…

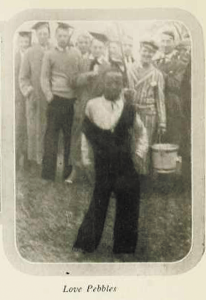

The 1929 edition of “Ye Domesday Book,” Georgetown’s yearbook, includes a photo of a young boy. Centered and foregrounded, the boy stands — swaggers, really — arms akimbo and left hip popped. Practically dripping with minstrelsy charisma, he looks like he could be turning at the end of a runway. He is a performer.

Like any good performer, he has the attention of his audience. There is a beaming crowd of men behind him — but they look different from him. In the photograph, the boy is mostly likely 11 years old; the men, mortarboards and all, are about to become college graduates. The boy is wearing dark overalls and a light shirt. The men are wearing sweaters, slacks and jackets. The boy is black. The men are all white.

The caption: “Love Pebbles.”

There are dueling interpretations as to how an 11-year-old black boy named Raymond Medley came to be known to Georgetown as “Pebbles.” Bill Bain (SFS ’76), had this to say of the moniker in a 1976 letter to the editor of The Hoya:

“Pebbles was so nicknamed, as the story goes, as a result of throwing, you guessed it, pebbles at the first girls that entered the front gates of this hallowed institution. A guardian of the status quo at that time and referring to the young ladies as a ‘herd of cattle,’ Pebbles quickly became an expert marksman with Hoya concretum.”

Medley, of course, would never study at Georgetown.

But he was a campus institution — on equal footing, according to some students, with the Jesuits and the Healy Clock Tower. In 1976, one student facetiously claimed to The Hoya that all decisions of real importance at the university should be lodged with “Pebbles.” In 1975, another recommended that incoming freshman meet Pebbles, their deans and their professors, in that order. Between 1963 and 1980, Medley appears in the pages of The Hoya no fewer than 45 times.

In a November 1984 issue of Sports Illustrated that carried John Thompson, Patrick Ewing and a tiny by comparison Ronald Reagan on its cover, the juggernaut basketball coach offered his own theory:

“Let me tell you why he was called Pebbles. It’s his hair, man. The Georgetown students used to rub Medley’s head for good luck. He was a mascot. Like a bulldog. His hair grew in tight, kinky curls. It’s like rubbing pebbles.”

* * *

Raymond Medley spent his whole life in Georgetown. He was born at Georgetown University Hospital in 1918 and grew up at 37th and Prospect streets, about where the brutal rear of Lauinger Library now hulks. Little is known of his family members, including their occupations — or fates.

He did have two siblings, and sometime around his ninth birthday, Medley came to the attention of the football team, who practiced on the front lawn. As a neighbor asserted, the Medley boys could play ball. He was adopted by the team, according to one source, as “a mascot of sorts.”

The name Pebbles appears several more times in yearbooks in the 1930s. But around there, the trail seems to go cold. Raymond Medley does not again become a point of conversation until the 1960s.

At least two milestones came to pass in the meantime. Sometime around 1942, when Medley would have been in his mid-twenties, the university’s athletics department hired him, where he worked for the next 27 years, eventually becoming assistant equipment manager. And at a date that cannot be determined with any certainty, Medley began to drink to the point of alcoholism.

In the 1960s, Medley begins to appear again in the sports section of The Hoya, usually with the baseball team, whom he helped coach. But at least as often, Medley graced these pages as a spectacle.

For much of Medley’s later life, his drinking problems and irregular employment were the subject of gossip, the object of consternation and the butt of jokes. In the 1976 April Fool’s Day issue, the staff of The Hoya joked that Medley had been fired for excessive drinking. The fake headline read: “Georgetown Fires Pebs; Students Cry ‘Dummies.’” Asked what he was going to do next, the fictitious always-crocked Medley responded that he was going to the pub.

Pebbles made his way into at least 13 April Fool’s Day issues. Often, Georgetown’s star was cast in a supporting role, his name usually slipped somewhere into the April Fool’s masthead.

Other times, the man himself “spoke.” In the 1972 edition, the paper conducted a fake interview with Pebbles, asking him “what if anything was the real reality of G.U.” Pebbles’ imagined response: “You mean the reel reality? Haw, s- – -, fella. Don’ ask me!”

The 1975 edition featured an advice column with the Rev. Raymond Medley, S.J.

Throughout the 1960s, Medley’s presence was mesmerizing. Pebbles fascinated Hoyas every day of the year. In 1966, an unnamed college prefect, speaking of Georgetown’s bureaucracy, asserted to this paper, “You’ll send around from office to office and finally you’ll come back and say, ‘I think Pebbles runs this university.’”

But in 1969, Medley nearly met his match. In an instance of art imitating life, Col. Robert Stiglitz, the new assistant director of athletics, fired Medley for “repeatedly being intoxicated while at work.” Stiglitz, who explained to The Hoya that he was “sorry about it … but had to fire him,” touched off a firestorm. Future Illinois governor Pat Quinn (SFS ’71) ran a headline in The Hoya that read “Pebbles Purged.” A student constitutional convention gathered in response to the dissolving of the original student government in 1968/9 stipulated as one of their demands that Medley be reinstated.

Stiglitz did not relent. “I’m made out to be the bad guy, the hatchet man, but I’m just doing my job,” Stiglitz protested. “Pebbles wasn’t doing his job.”

By that point, Medley was 51 years old. He had been a part of the university community for 42 years, and an employee for 27. In that time, he had crashed alumni parties, received multiple formal reprimands for failure to show up to work and seen a university moderator and sociologist, after which the odds of his rehabilitation were judged to be slim. Medley received four weeks’ severance and no pension. Toward Stiglitz, Medley did not mince words: “That man is an idiot,” he told The Hoya.

When asked what he did when he found out he had been fired, Medley explained that he had gone to watch a movie and gotten stoned. In the days that followed, Medley, who was widely known as the Hoyas’ “No. 1 fan,” would be barred by Stiglitz and the Athletic department from basketball games, put into open conflict with the university and forced to reckon with whether he could return to Georgetown at all.

* * *

Medley’s dismissal, as severe a blow as it seemed at the time, was the beginning of the leading man’s third act. Although he skipped his first two interviews, Medley was offered a job as porter for the Jesuit community. Although several Jesuits shared that they doubted Medley was ever employed by the Jesuit community, the written sources, including obituaries, were unanimous. What is clear is this: Medley didn’t leave Georgetown. His reputation simply grew.

In the spring of 1972, Stiglitz resigned his post under fire from students, with whom he was becoming increasingly unpopular. It was no surprise. Medley told one Hoya reporter, “I’m never gonna leave.” That March, a headline blared “Pebbles Is Not Alone,” referencing the possibility that a black coach would lead the basketball team. John Thompson Jr. was about to burst onto the scene.

And then the Thompson era landed like a thunderbolt. By 1976, Thompson had been selected by Dean Smith to serve as an assistant coach for the gold medal Olympic basketball team. In 1984, Georgetown captured the NCAA championship.

The racial transformation that attended the Thompson era was not without its casualties, John Thompson himself almost among them. In 1975, before the team took off, the peanut gallery was calling for J.T.’s head. At a home game in McDonough Gymnasium, a group of students rolled open a vicious banner: “Thompson the n- – – – – flop must go.” But Thompson stayed and Thompson triumphed.

Thompson confessed that he did not know how to deal with his team’s biggest fan: Raymond Medley. The gladiator began to outshine the minstrel, and Medley embarrassed Thompson, who told Sports Illustrated’s John Wideman, a major black novelist and essayist, that he would hide when he saw Medley coming. Thompson compared Medley, who would often embrace the female cheerleaders uncomfortably, to Dancing Harry, a popular 1970s figure at basketball games who would entertain crowds with his bizarre dances. To Thompson, Medley performed an old sort of blackness that Georgetown was then in the busy process of displacing.

But Medley, like an old fielder, ground on for another decade. Students, at once covetous and distant, continued to fete their jester. One article makes mention of an annual “Pebbles’ birthday party” on the third floor of Ryan Hall. Students frequently entered Medley in Alpha Phi Omega’s Ugliest Face on Campus fundraiser. One year, the nomination claimed that “the department of health once condemned Pebbles’ face.” An alumnus who graduated in 1981 told me Medley may have lived in a small room above Ryan Gymnasium, but he was not sure.

Then, in 1982, it all stopped. That year, on June 10, Medley died where he was born — Georgetown University Hospital. That year, the Hoyas surged to the finals in the NCAA Tournament only to suffer a heartbreaking loss to Dean Smith and Carolina.

One source cited the causes of death as “old age” — although he was only 64 — “and drinking [that] had caught up with him.”

Medley’s star faded dizzyingly fast. When I asked Fr. Kevin O’Brien, S.J., who arrived on the Hilltop in 1984, if the names Pebbles or Raymond Medley meant anything to him, he confessed that they did not. “We did not hear much about him,” O’Brien wrote in an email to The Hoya.

Another Jesuit shared with me that amnesia toward Medley did not surprise him. He described the relationships most students had with the man as “superficial.”

All told, Raymond “Pebbles” Medley spent 55 years on the Hilltop, from the time he became unofficial mascot for the football team at age nine to his death at 64. In that time, he occupied an uncomfortable position — one that was supposed to have disappeared when, in the 1870s, we selected Patrick Healy as president and hoisted the Blue and Gray to signal our readiness to set aside the past. Under interrogation, that story does not hold up.

What rings true is this: Once, there was a man named Raymond Medley. Georgetown remade Raymond, and he spent his life here. “Pebbles” was tradition, heritage — he was a Georgetown original.

John Thompson seemed to recognize as much in 1984. That November, describing a photo of Raymond Medley he kept on his desk, Thompson told Wideman:

“[Medley] grew up here, and they expected him to be a clown, as mascot. That’s all he knew and that’s what he became. The students didn’t see anything wrong. It’s what they were taught. So I became a little ashamed about being angry at Pebbles. I named one of our basketball awards after him — the Raymond Medley award for sportsmanship. His life wasn’t easy. He did the best he could. I keep his picture to remind me.”

In 1980, Tom Egan, writing in these pages, put it more bluntly. “Pebbles,” he wrote, “exists only at Georgetown. Pebbles was born the first time he walked through the doors of McDonough Gymnasium. Before that time, he did not exist. Whoever he was and whatever he did, he was not ‘Pebbles.’”

Editor’s Note: Matthew Quallen’s “Hoya Historian” column generally runs on A3 every other Friday. In the process of researching for this week’s iteration, Quallen stumbled upon a topic that merited expanded space, and thus, “Hoya Historian” became our Friday feature. This piece retains the facets assigned to signed columns, and is the viewpoint of its author, not indicative of the editorial position of this newspaper.

Ray O'Connor Jr. C'73 • Sep 30, 2015 at 10:00 am

While I enjoyed this article, I’d like to offer some observations. The AD was Col. Robert Sigholtz and he was terminated by then president Robert Henle SJ. As a student manager of both the basketball and football teams, I shared some wonderful moments with Pebbles, who truly loved Georgetown and its students.

Phil (PB) McDonough C'68 • Sep 26, 2015 at 12:27 am

Exceptional piece! Interesting that Raymond’s fascination with Hoya co-ed’s may have begun at the admission gates! He certainly was fond of many of them! While his demon was legendary, he was a friend to most everyone who frequented McDonough, helping with mental aspects of one’s game, encouragement, equipment needs, and ‘cover’ of various sorts for residents and team members.

Rashid Darden, C'01 • Sep 25, 2015 at 7:59 am

Thank you, Mr. Quallen, for this column and all the others.