The Working Group on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation held a teach-in event focusing on Georgetown’s relationship with slavery and announcing the implementation of Freedom and Remembrance Grants and an Emancipation Symposium to address that history for an audience of around 150 people in Gaston Hall on Tuesday. The event comes in response to university-wide activism surrounding the legacy of slavery on Georgetown’s campus and demonstrations against instances of institutional racism on college campuses nationwide.

Working group chairman and history professor Fr. David Collins, S.J., led the conversation, which began with Matthew Quallen (SFS ’16) outlining the history of slavery at Georgetown. Quallen, who received a Marshall Scholarship this month to study the dehumanization of groups through history, published a Sept. 2014 viewpoint article in The Hoya that detailed Georgetown’s slaveholding past, sparking conversation and action from the Georgetown community.

“The Jesuits who supported the university held literally hundreds of people captive across generations over a century, entire families and lives passing by in slavery,” Quallen said in his lecture.

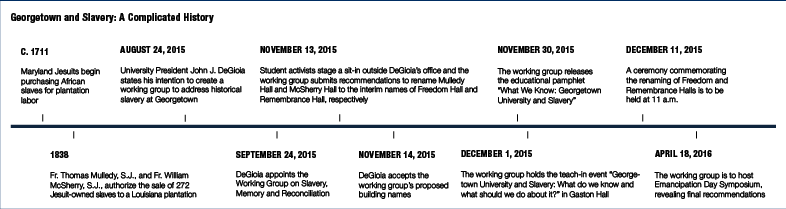

The Office of the President formed the working group this September to address the consequences of the university’s history with slavery. The event comes in conjunction with the working group’s recommendation for the interim renaming of former Mulledy and McSherry Halls to Freedom and Remembrance Halls, respectively, following student protests. The group’s recommendation was approved by University President John J. DeGioia and the university’s board of directors Nov. 14.

Associate professor of history Marcia Chatelain — who formerly taught at Brown University — and University of Virginia professor Kirt Von Daacke presented to the audience the ways in which both Brown and UVA have addressed their own histories with slavery.

Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs faculty member and former South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Research Director Charles Villa-Vicencio also presented lessons from reconciliation efforts following South African apartheid, citing similarities between the post-apartheid and post-slavery periods in South Africa and the United States, respectively.

Slavery at Georgetown

Quallen traced the story of slaves at Georgetown back to the 17th and 18th centuries. He described the grant of 12,000 acres of land to the Jesuits by Governor of Maryland Lord Baltimore upon their 1634 arrival in the colony.

The Jesuits utilized the grant for plantations as a source of funding; initially, Quallen said that Jesuits used indentured servants to work the land, but the availability of these servants declined in the 18th century. Soon after, the Jesuits began purchasing African slaves. By 1763, the Maryland Jesuits held approximately 200 slaves.

During his remarks, Quallen highlighted the humanity of the Jesuit-owned slaves who were held as property, telling the story of a 48-year-old woman named Fannie, whose family of 12 was most likely sold by Georgetown Jesuits in 1817.

According to Quallen, during the early 1830s, many Jesuits — including former University President Fr. William McSherry, S.J. — complained that the plantations were failing to produce profits and proposed a mass sale of slaves in order to generate greater revenue.

Fr. Thomas Mulledy, S.J., and McSherry, after receiving permission from Rome, executed the sale of 272 Jesuit-owned slaves for over $100,000 to the owners of a Louisiana plantation in 1834.

Under conditions placed on the sale from Rome, Georgetown was not to use the profits from the sales to pay down debts, such as those accrued during the university’s expansion. The families of slaves were not to be separated in the sale, and slaves were supposed to be able to receive holy ministry.

“To our knowledge all of the conditions of the sale were violated [by Georgetown] in some way or another,” Quallen said.

Concluding his remarks, Quallen explained that the working group is not yet finished investigating Georgetown’s history with slavery. Quallen — who investigated Georgetown’s slave-holding past through university archives — said there is still more work to be done.

“There is probably much more that hasn’t been explored and questions remain,” Quallen said.

Models for Progress

Brown and UVA utilized different approaches in reconciling their own relationships with slavery in the past decade.

Chatelain delved into the details of Brown’s approach in navigating its complex racial history, which includes being named after a family of merchants who financed slave voyages to Rhode Island in the 1700s.

“If I could characterize Brown University’s approach to this question, I would say that Brown played the long-game in investigating its history and really thinking about the action steps to reconciling it,” Chatelain said.

Beginning in 2003, Brown assembled a committee to investigate the university’s relationship with slavery. As a result of the committee’s work, Brown placed a memorial to the slaves of its past in the center of its campus, revised its official history to acknowledge its slave-holding past and extended a $10 million yearly grant to help Providence’s long-disadvantaged public school system, among numerous other reforms.

Chatelain explained that Brown’s actions, while successful, were not a cure-all for the university and its issues of race and slavery.

“The last point I want to make about the work that Brown did — although we consider it the gold standard of institutional responses to this history — it did not solve all of its problems,” Chatelain said.

According to von Daacke, the UVA commission to investigate its own historical ties to slavery was formed after 15 years of faculty, student, alumni and community members worked to compel UVA to acknowledge its ties to slavery. UVA founder Thomas Jefferson held hundreds of slaves during his lifetime.

Since the formation of the commission in Apr. 2013, UVA has seen developments in recent years that include several monuments and plaques honoring the slaves that once lived and worked on and near the campus. Along with other initiatives, UVA has created a class to teach students about the school’s relationship to slavery and has named a dormitory in honor of two slaves, William and Isabella Gibbons, who were enslaved by UVA professors.

Von Daacke said that cooperation between all of the different groups constituting a university community is critical to adopt reforms. He also said that the process at Georgetown would be slow, but progressive.

“[I]t’s collaboration — students, community, faculty, administrators, staff — everybody has to be brought to the table,” von Daacke said. “It takes time to gain trust and initiate meaningful dialogue. It’s going to take more than just your fleeting four years here to do this. This is something that you have to pass on to the next generation of students.”

Lessons from South Africa

Villa-Vicencio, who served as national research director on the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 1996 to 1998, a commission formed to address victims of human-rights violations under apartheid, reflected on his experience and offered his thoughts on memory and reconciliation in light of racial strife in South Africa and on college campuses nationwide

“Some of us just don’t have it within us to forgive the suffering and the tragedy that we may have faced,” Villa-Vicencio said. “I would like to suggest that a middle path is not forgiveness, but reconciliation.”

Villa-Vicencio added that in light of past societal tragedies, it may be best to recognize the past in order to overcome its tangible implications today.

“The past cannot be undone,” Villa-Vicencio said. “It can be acknowledged. … It can be managed, through the unlimited participation of everybody involved.”

Georgetown’s Plan of Action

The event ended with the unveiling of the working group’s newest policies, and announcing its decision to divide its 16 members into four issue-specific subsections to better formulate recommendations to the Georgetown community.

One subsection will focus on history and action concerning Georgetown’s archives. A second emphasizes Georgetown’s ties to local history in slavery, and a third works on topics of memory and memorialization. A fourth group will reflect upon reconciliation and ethics within Georgetown’s community.

These subsections have yet to convene and their recommendations will not be known until after the working group’s next meeting in mid-January.

The Working Group also introduced the Freedom and Remembrance Grants. These grants are a $10,000 initiative running until the end of the current academic year in which working group-approved students and faculty will receive amounts of up to $500 to sponsor creative engagement that promotes reflection on the issue of slavery at Georgetown.

The Working Group stressed that members of the university community interested in applying for a Freedom and Remembrance Grant, or in providing suggestions to the working group, can do so through its web page.

The working group additionally announced an Emancipation Symposium to be held April 18 and a ceremony commemorating the interim renaming of Freedom and Remembrance Halls on Dec. 11. The Emancipation Symposium will serve as a space for discussion and speakers on the topic of emancipation.

Georgetown University Student Association Vice President Connor Rohan (COL ’16), who attended the event, said that events of this type strengthen the university community.

“As Georgetown students, we have an obligation to learn about the sins of Georgetown’s past and how they continue to resonate today,” Rohan wrote in an email to The Hoya. “Events like these achieve that goal and bring our community closer together as a result.”

Sitaara Ali (COL ’17), who also attended the event, said that she thinks students should be more involved in response to the issue and continue to engage in the learning process.

“I wish more students were involved and understand that Georgetown has a history of slavery,” Ali wrote in an email to The Hoya. “I think the most important thing we can do now is learn from that history.”

Other students in attendance shared similar sentiments, with many wishing to see the community further acknowledge and engage with its emerging history.

Ebony Thomas (COL ’19) said she wants the Georgetown community to know that students and activists heed the working groups recommendations about Georgetown’s history with slavery and look forward to future dialogue.

“Just know that there are people listening and paying attention and want to know what their thoughts are about how we should move forward with the university,” Thomas said.

Collins closed the event with a hopeful sentiment for solidarity in the Georgetown community.