“Beetlejuice, Beetlejuice, Be-” Let me stop you right there.

Growing up in the early aughts conjures a variety of nostalgic memories. From Disney DVDs to the multicolored scooters in gym class, there’s a certain curated essence to our shared childhood experiences. For many, this includes the watching (and rewatching) of hauntingly mesmerizing Tim Burton movies.

From “Edward Scissorhands” to “Corpse Bride,” these films were often the gateway drug to pseudo-horror. Now, his productions threaten to taint these fond memories with their blustering attempts at new-wave media, as evidenced by his newest sequel, “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice.”

The movie takes place 36 years after the original, opening with Winona Ryder reprising her iconic role as Lydia Deetz, the host/in-house psychic of what seems to be a wildly popular program, “House Ghosts” (for those unfamiliar, this was nearly the title of the original movie). From there, we watch as Lydia’s life is frequently interrupted by sightings of Beetlejuice (Michael Keaton), which makes her resort to pill-popping and the subsequent enabling from her boyfriend/manager Rory (Justin Theroux). Following the violent death of her father, Lydia, alongside Delia (Catherine O’Hara), prepares for the funeral by ensuring that the whole family is together: including Lydia’s estranged teenager, Astrid (Jenna Ortega).

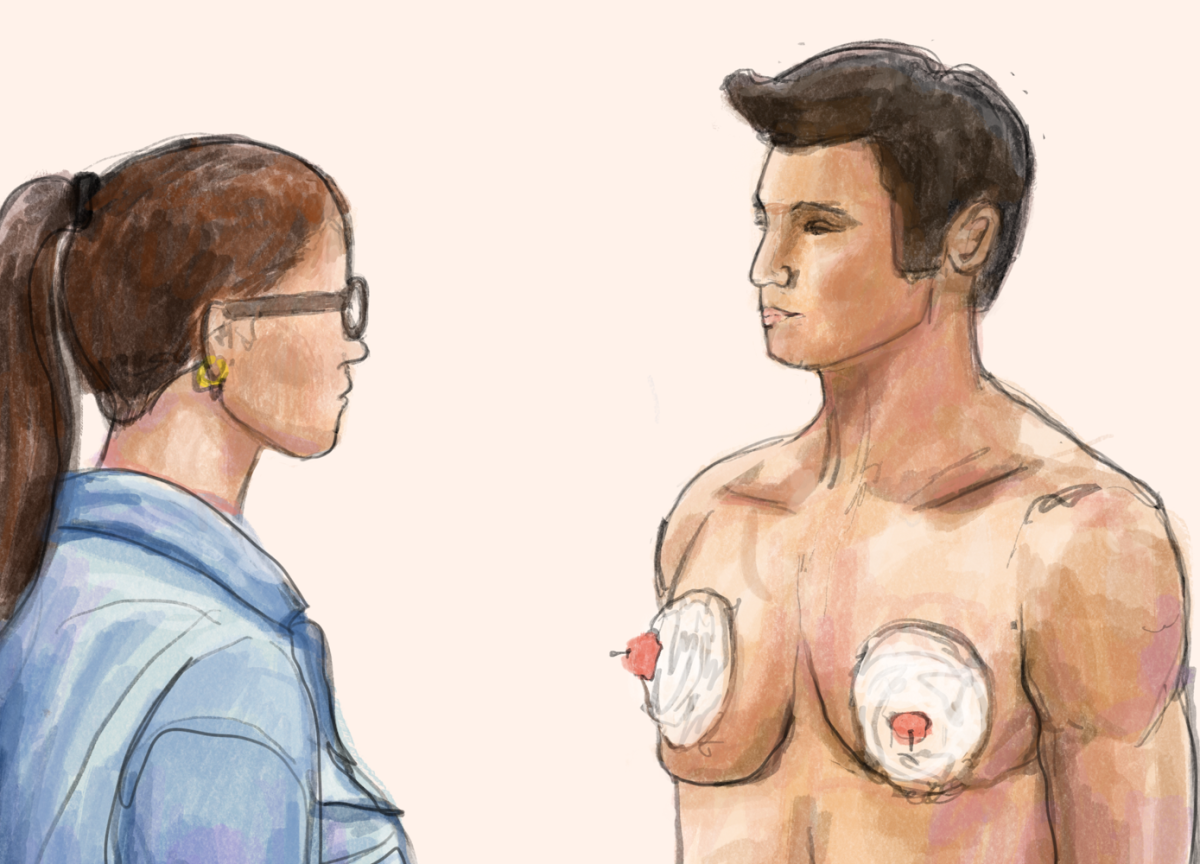

In the afterlife, a parallel plot line is being put together — literally. This story of this realm begins with Delores (Monica Bellucci), Beetlejuice’s ex-wife and current leader of a soul-sucking death cult, stapling her severed body parts back together and heading out on the hunt for her former beau. Beetlejuice, meanwhile, is focused on getting Lydia back, armed with a picture of her from her last visit to the underworld and his undying love.

Unfortunately, audiences don’t have to wait long for the first disappointment of the film: the downfall of Lydia Deetz. For a generation who idolized the subversive goth teenager since 1988, watching a beloved character become an easily manipulated, and often verbally abused, shroud of what she once was, Lydia became a depressing reminder that passion and vigor frequently die even before we fully “grow up”. Even Delia encourages Lydia to grow a backbone, so to speak, but the only time that she shows a shred of decisive action is when her maternal instincts kick in during her attempts to save Astrid from a soul-swapping mission with a parricidal treehouse-dweller (but we’ll get to that later).

Speaking of which, the antagonists of the film are inherently unsatisfactory to viewers who were used to the original villainous shenanigans of Beetlejuice.

First off, cult leader Delores barely speaks throughout the movie, instead spending her time sucking the soul out of men. Her history is told by a man, Beetlejuice, who describes her insatiable lust and beauty. Her only goal is to vengefully claim the soul of her ex-husband. Catching on to a theme here? Burton’s directorial choices lean more toward a sensual projection of the male gaze upon the scorned woman trope rather than any substantial character development of Delores that would add depth to the original film.

However, the secondary antagonist in the human realm is a bit more to chew on. During their return to Winter River, Conn., Astrid meets resident Jeremy Frazier (Arthur Conti), who she immediately becomes emotionally entangled with. The two bond over vintage records, Dostoevsky and parental issues, eventually leading up to a romantic swell on Halloween — until Astrid finds out he’s a ghost.

Jeremy’s service to the plot is clear: he gives a catalyst for Lydia to reenter the underworld, provides an opportunity for the estranged mother-daughter pair to reconnect and necessitates a bit of character development for Astrid, drawing her into the forefront of the film. He manages to deceive audiences, pulling off one of the only plot twists of the movie through a convincing performance as a textbook male manipulator.

Overall, the energy of the film just fell a bit flat in comparison to the original movie, or even other iterations of the storyline. Burton spent so much time attempting to appear relevant to a new generation by including Rory’s semi-ironic therapy buzzwords and Astrid’s climate change activism that the real subversive spirit of the original production was lost along the way.

Although the principal character plot lines left much to be desired, the film itself provided a forum for fans of the “Beetlejuice” enterprise to see their favorite parts of the franchise again. Between Beetlejuice’s snappy one-liners, the reappearance of many familiar favorites (such as the Maitland model and the trademark song “Day-O” at the funeral) plus two more almost-weddings, this production undoubtedly succeeds at paying homage to the original.

For extreme fans of the franchise, this might be all they need to call it a success. For those hoping for a fresh play on the plot, you’ll only find the same tropes scaled down to their most reductive. However, three decades later, I think we were all left wanting a little more. “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice” ultimately nods too heavily to its original, making it as repetitive as its title.