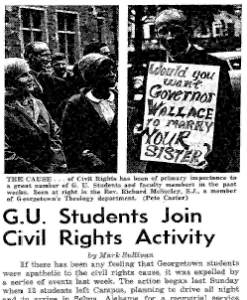

G.U. Students Join Civil Rights Activity

“If there has been any feeling that Georgetown students were apathetic to the civil rights cause, it was expelled by a series of events last week. The action began last Sunday when 13 students left Campus, planning to drive all night and to arrive in Selma, Ala. … To avoid trouble on the road, the students travelled under the pretense that they were going to New Orleans for spring vacation …”

And so begins an archived March 26, 1965 article of The Hoya, titled “G.U. Students Join Civil Rights Activity.” Two years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, the civil rights movement was beginning to mobilize the public in greater numbers, both across the nation and on the Hilltop.

Forty-six years later, Washington, D.C. is unveiling a long-awaited monument to the man lauded as an inspiration and source of sweeping social change. Heralded for his wisdom and charisma, King stood as an example for a generation seeking to change the status quo. For Georgetown students who experienced his incredible spirit firsthand in the heat of the civil rights movement, it was an experience of a lifetime.

HEADINE TO THE BATTLE LINES

In the spring of 1965, co-founder of the Georgetown University Community Action Program Ron Israel (SFS ’65) and East Campus Junior Class President, now-Ambassador, Phil Verveer (SFS ’66 ), headed up a group of 13 students traveling to Alabama. As they set off on their quest to promote social change, the full ramifications of what was to come had yet to sink in.

After arriving in Montgomery, the group was encouraged by Montgomery Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leaders to spend the night there before continuing to Selma. The Georgetown students, along with local SNCC members, were then staging a peaceful sit-in at committee headquarters when they were met by police. According to the 1965 article in The Hoya, Montgomery police mounted on horseback, along with a “posse” of red-hatted volunteer citizens and rode into the demonstrators, killing an elderly woman in their path. In response to the brutality, SNCC staged its own march the following morning that was met once more by the same force.

“They were hostile. They broke things up, they put out dogs, they shot teargas pellets at the demonstrators. There were some people who stayed despite of all of that, and those people were put in jail,” Israel recalls. “I didn’t end up going to jail myself, but a couple of students did.” The Montgomery demonstrations were led by two of King’s lieutenants, Andrew Young, who later went on to become aU.S. ambassador as well as mayor of Atlanta, and Jesse Jackson, the prominent civil rights activist.

“There was a certain element of fear, but the environment that was created by Dr. King and Andrew Young and the African American demonstrators really did a lot to ease that kind of emotionality,” Israel says. “We felt relatively protected by the greater mass of people engaged by this.”

Urged by leaders of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the displaced protesters found refuge in the church. Once inside the safe haven, Israel, Verveer and the other protesters heard the sermon of the dynamic King.

“It was electric,” Israel recalls. “It was amazing, he had the power to put a spell on the room and change the environment and uplift people. He made them feel that what they were doing was right and just and get them motivated to take action.”

Verveer noted the pastor’s charisma and effect on the crowd: “King’s arrival was one of those things that made people feel like there was a center of gravity — in this case an individual that was able to lend a sort of cohesion to this or at least give it a certain direction, and all of this turned into something.”

That afternoon in the church was the first time Israel heard King speak live, a life-changing moment in his eyes. “To hear him speak was a powerful, transforming experience,” he says.

Israel notes that in spite of their racial differences, the church members and white protestors alike were united by the message. “It was an unusual time — it’s hard to explain this nowadays — we were there when the civil rights movement was just coming into its own and the spirit of nonviolence and cooperation that emanated from Dr. King’s tradition very much ruled the day.”

Spurred on by the movement, Israel held down the fort as Verveer flew up to D.C. to spread the group’s message to the Hilltop. Upon his arrival, the East Campus Student Council held an emergency meeting and passed resolutions sympathizing with the civil rights movement. The resolutions stipulated respect for individual students involved in the movement, a bold move since support was not widespread at the time. The resolutions also established a fund for the movement as well as petitioned for federal protection of the students protesting in Montgomery.

Verveer teamed up with senior Michael Lenaghan (SFS ’65), another GUCAP member, to lead a march of faculty and several hundred students to the White House to present their petition to Clifford Alexander, an assistant of President Lyndon Johnson. Applauding the recently passed Voting Rights Act of 1965, the petition read, “You, Mr. President, have acted rightly and with conviction to cure the injustices that have occurred in recent weeks.”

A DIFFERENT CLIMATE

But the social climate in the District was in some ways akin to the violent reactions facing the Alabama students the previous day. “Even in Washington where on a normal day people disagree, folks at the time were really animated,”Lenaghan says. He describes systematic resistance to the student’s movement, culminating in police action against the protesters yet again.

“Later that day [after the White House march,] I spent a lovely evening in jail,” Lenaghan says. “And I guess six or seven times in the course of three years.”

“Law enforcement was correct — there was civil disobedience involved — but again, it was because folks who physically [responded to the protesters], not the police … that the police had to intervene. And that included jail, but never more than a night or two.” Lenaghan admits that at the time it was scary, but he cites the support of the Center for Creative Nonviolence as key to protecting him and other protesters. Furthermore, the diverse backgrounds of civil rights supporters meant that someone always knew someone else who could help a protester get out of jail or provide legal defense.

“But being a peaceful guy doesn’t mean people don’t treat you violently — and you’re the one who goes to jail sometimes,” he reflects.

A JESUIT INFLUENCE AT WORK

In spite of the adversity, Lenaghan attributed much of the energy in the campus movement to Fr. Richard McSorley, S.J., who was an adviser to King as well as a confessor for the late President Kennedy. On the Hilltop, however, the fiery Jesuit was more widely known as a vocal leader advocating social justice.

“McSorley was considered a social radical,” Lenaghan says of his former freshman dorm master.McSorley, in fact, introduced him to the founders of the Center for Creative Nonviolence, a Hilltop “channel full of people who might change things,” according to Lenaghan.

Criticism of McSorley from some within the Georgetown community was not unusual — and if anything, such was the norm in 1965, as the counter-culture movement incited by protest against the Vietnam War had not yet swept through campuses nationwide.

“There were people that thought that civil rights ‘nonsense’ was an aberration, and furthermore, there were wars to fight, things to do, and Dr. King was a ‘communist’ and what have you,” Lenaghan says.

“There was honest and sometimes heated disagreement. There were folks … that had vehemently different views that the federal government shouldn’t get involved.”

While Lenaghan spoke favorably of the “honest discourse” and that these differing views were both “a great learning and tumultuous period,” by no means should the campus climate be seen as unified at the time.

ANOTHER TIME, ANOTHER CAMPUS

“It wasn’t like we were living in a nest where everyone agreed with us whatsoever,” says Lenaghan. “And that was what was challenging — because perhaps if you didn’t feel as strongly, [then] you didn’t speak as loudly or stick your neck out. But if you did — you realized, hey not everyone agrees with me.”

What’s more, with the exception of those like McSorley and GUCAP activists, the civil rights movement was not the predominant cause on the Hilltop.

“I don’t think it was an enormous preoccupation on campus. Georgetown in those days was a very homogeneous community, enormously Caucasian,” Verveer observes. “It wasn’t a student body that I think I would describe in the early ’60s as enormously socially aware.” He notes that in 1965, the campus was much less diverse, in terms of race as well as gender, and counterculture had not yet shaken the conservative and insular community. “I don’t want to [suggest] that Georgetown wasn’t a place with a social conscience. Georgetown was obviously very disposed to trying to promote a just society — but again, it was a very decided view of life.”

“The campus between 1966, the year I graduated, and the campus in 1968 were almost like they were different worlds. So much changed in such a short amount of time,” he says.

For Verveer, the 1965 march was relatively unorganized. But the excitement of the movement, both chaotic and charismatic, energized the students. The legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., now crystallized by history, could easily be taken for granted by some 21st century students.

“But one doesn’t have an omniscient view as you might have reading about history or seeing a movie about it or whatever,” he reflects, noting the uncertainty of their activism. “If you are in the midst of something, [you’re] relatively confused with uncertain outcomes and not knowing really much what’s going on any place else.”

SET IN STONE

While 1965 may be remembered for the virulent division in the country, the nation has begun to emerge from its fractured past through the leadership of individuals like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

King triggered a wholesale social shift that saw greater equality and tolerance of all people. It has been almost half a century since the Baptist minister began spreading his message and inspiring millions across America, including to the Hilltop’s students.

“I was fortunate enough to be in college during that time. It was a very hopeful time, and a lot of positive change was brought about in a constructive way, using Dr. King’s beliefs of nonviolence,” Israel says of King’s impact on the movement, as well as his own life. “That part of it is his legacy, and that part of it hopefully is a message that can resonate through this memorial to other people.”

Over 40 years since the leader’s death, Israel notes that such a dedication on a national scale is “longoverdue.” But at least now, future generations will continue to stay aware of the significance of the role that he played in transforming modern-day society.

“He definitely was a major changemaker.”