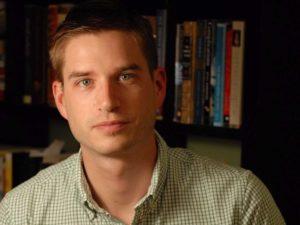

Cal Newport, associate professor of computer science at Georgetown University, has never had a social media account in his life. The author of five self-improvement books focused on academic and career success, Newport advocates for eliminating a digital dependency to produce “deep work” — periods of intense focus undistracted by email or social media.

Newport details his philosophy for success in his blog Study Hacks, which explores “how to perform productive, valuable and meaningful work in an increasingly distracted digital age.”

Amid midterm season, The Hoya spoke to Newport about common misconceptions students harbor about productivity, the addictive nature of social media and his tips for success in studying.

What are the biggest mistakes people make in their work?

Back when I was an undergraduate [at Dartmouth], to research a book I ran an experiment where I studied the study habits of 50 different very high scoring students across the country. One of the biggest differentiating factors is students think about studying as a skill that they are constantly practicing and improving. I think the biggest mistake students make is that they don’t think much about how they study, they just sort of go and ‘study.’

How did you decide to write your first book and what was that process like?

I wrote two books while an undergraduate, and the second one was about how to study in college. The motivation was pretty simple: After my freshman year, I decided I wanted to get more serious about my study habits because I wanted better grades. I ran a bunch of experiments on myself on how I studied. I didn’t get smarter between my sophomore year and freshman quarter, the difference was I spent a few months thinking really critically about how I studied, how I took notes, how I wrote papers.

So, according to your findings, how should students study?

Studying is a skill that you can be good or bad at, and most students are bad at it. They are spending way more energy and getting worse results than they could be. The general mindset, I used to call it studying like Darwin, because you constantly want to be evolving your study habits, trying to question and deconstruct how you’re doing your work. Working with your intensity of focus is a core resource for getting your work done efficiently. Things that we know now from research is the attention residue effect. Even a quick glance at a distraction, like a quick glance at your phone, reduces your cognitive capacity and can last for a little while. It’s not how long you’re distracted, it’s just the fact that you changed your context.

Do you think multi-tasking is actually possible?

No, and what’s important is that most people already intuitively understand you can’t do multiple things at the same time. It’s really just this single-tasking with a lot of quick checks. They say, ‘I’m not multi-tasking, I just have my Word open, I’m just writing my paper.’ But, if you’re still doing the quick checks every few minutes, it can be just as bad as having multiple things open. What your mind can produce if you go one or two hours with zero context switches is massively more valuable.

Do you think we could be addicted to social media?

Yes. One of the little-known truths about Silicon Valley is a significant number of the major executives in charge of these companies do not let their kids use their product. Social media is run by very large companies who make money by extracting time and attention. Facebook’s market evaluation is almost twice as large as ExxonMobil. Because of that, significant engineering goes into place to make these an addictive experience and something that you want to keep checking. It is not a lack of willpower on your case, it’s engineered into the product, even the basic dynamic of clicking ‘like’ icons on posts that spread through all social media apps purely for addiction-inducing reasons.

What [companies] needed is what they call “social approval indicators.” They needed a stream of things in your account that show that people approve you, and they needed to arrive unpredictably, so you never know if you have some more of those.

How would you describe your personal usage of social media and the internet?

I’ve never had a social media account. What I do recommend to people is to take it off your phone. None of the reasons anyone has as to why they need to use social media requires the need to be able to do it any time on your phone. The only reason to have it on your phone is basically to serve their need, which is to give you something to do when you’re bored, so they can extract more minutes. If you simply take it off your phone, log in on your laptop, type in your password, you don’t lose any of the value you get out of it, but you immediately get away from the addictive part.

What is your biggest piece of advice to Georgetown students with an overpacked schedule trying to study for midterms?

Unpack their schedule, first of all. There is this misbelief that quantity is impressive, [that] the outside world is impressed by the quantity of things you do. Double majors are more impressive than one, 10 clubs is more impressive than two. It makes sense, because in a university setting, you want to stand out, you want to be ambitious. Especially when you leave college and go into the real world, very little credit is given for quantity. What people want to evaluate is how good are you at what you do best. One of the biggest competitive advantages you could have is attention capital, or your ability to concentrate.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

The value of active recall versus passive recall. Having to produce something from scratch is very hard, but it cements the concept much better than reading over it passively. When I studied the top-performing students from my book, none of them sit there with their book and read it. Instead, they would set up a prompt, and they would say, “Okay, I’m going to lecture this out loud. Can I do this in complete sentences, do I have a clear answer?” If they can lecture it out loud, clearly, they know it. It is the active recall that submits the information.