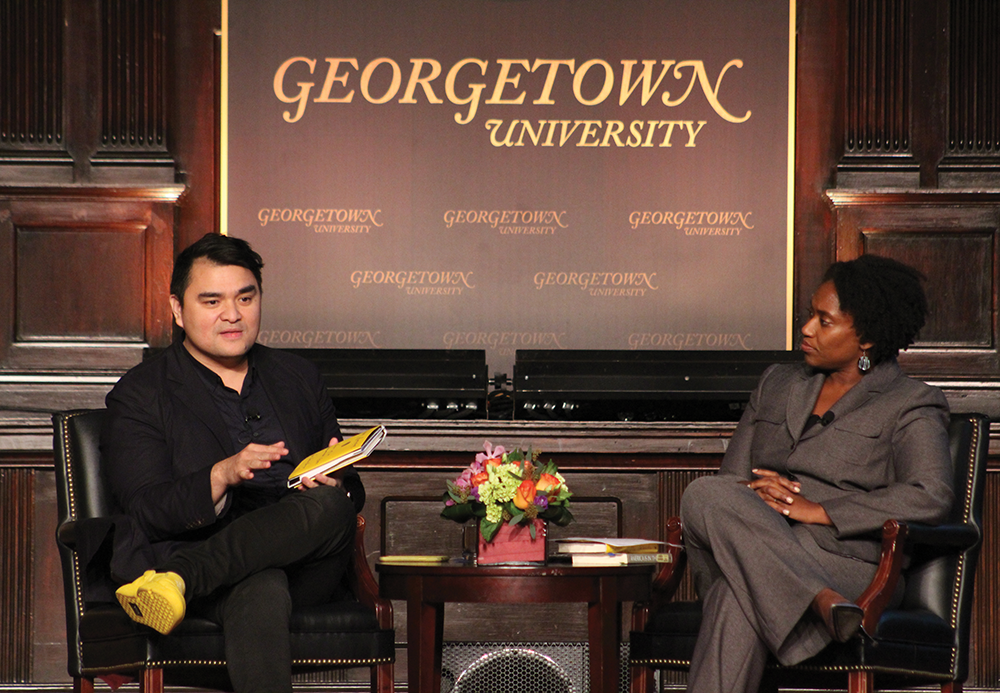

Media organizations exacerbate discrimination against immigrants without documentation by misconstruing the role that immigrants play in the United States, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas said at a Gaston Hall event on Wednesday.

The language used to describe immigrants without documentation in the media perpetuates the belief that immigrants without documentation do not contribute to the U.S. economy, Vargas said.

“I have lied my way through my career in journalism. I felt guilty I had to lie just to get a job. Undocumented workers contribute billions of dollars in taxes and social security and people don’t realize that,” Vargas said. “The master narrative and how we talk about ‘illegal aliens’ in the country is what propelled Donald Trump to the presidency. The media, specifically the media in D.C., has been complicit in that.”

Vargas won a Pulitzer Prize in 2008 as part of the Washington Post team that covered the 2008 Virginia Tech shootings, according to NPR. He was also nominated for an Emmy Award for Outstanding Documentary for his 2015 documentary “White People,” which addressed issues of race and identity in the United States.

Vargas is the CEO of Define American, a nonprofit media organization that uses storytelling to advocate for immigrant rights and fight discrimination. His new book “Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen,” chronicles the story of his life as an immigrant without documentation. Vargas said he will donate his honorarium from the event to UndocuHoyas, a student group that advocates for the rights of students without documentation.

Vargas reframed the issue of immigration for those without documentation as an issue about families.

“We can’t talk about the policies and politics of these issues until we understand the human part of this issue,” Vargas said. “This issue is not about immigration reform, not about border control or walls, it’s about families. Immigration has always been about families.”

The evangelical community offers a support network for immigrants without documentation in the United States and helps them feel more integrated into U.S. society, according to Vargas.

“I was at an event in Georgia, and I met a young Guatemalan man who said that he didn’t realize that white people liked him until they got into church, because that’s where they hugged,” Vargas said. “I remember he told me ‘When I walk into that church, I don’t need papers to be equal under the eyes of God.’”

Vargas, who only discovered that he did not have documentation when he was 16, said that the imperative for him to hide his identity damaged many of friendships and presented him with a personal struggle with his identity.

“Being in the undocumented closet was tough because I realized I wasn’t just hiding from the government, but I was hiding from myself,” Vargas said.

Despite the challenges that Vargas faced as an immigrant without documentation in the United States, his experience and time in the United States allowed him to achieve his professional and personal success, he said.

“It’s almost like America is one big dare: We are all being dared to dream as big as we can and find windows that reopen when doors close, to remind ourselves to be grateful,” Vargas said. “Even though [the United States] doesn’t know what it wants to do with me, it has dared me to be the person that I am.”

Minority communities in the United States must overcome their differences to advocate against discrimination, Vargas said.

“I think this is a time for us to figure out what bridges have to be built. In the immigrant rights movement we don’t do enough with the African-American community,” Vargas said. “We cut each other into pieces and create borders where there are none.”

First-generation college students can play a crucial role in reshaping culture in the United States, according to Vargas.

“First-generation college students are remaking America and what civic participation looks like,” Vargas said. “I used the word ‘citizen’ very deliberately because that’s what we have to have in common.”

He encouraged students without documentation to participate in U.S. politics despite their immigration status and to redefine what it means to be a citizen.

“I would argue that there’s a citizenship that is deeper than the law you pass and the papers you have and what you are born to,” Vargas said. “There is a citizenship of participation and we have to participate and really engage.”