For T’Keel Petersen (MSB ’12), seizing every opportunity at Georgetown has not come easily. To study abroad at Oxford University the summer after his sophomore year, Petersen was forced to weave together a patchwork of grants and contributions from extended family; the financial aid package that makes his enrollment at Georgetown possible did not extend to summer education.

But even once he gathered the necessary funds to go abroad, spending on group dinners and other activities dealt him a blow when he ran out of money with two weeks to go in the program. With a tone of relief in his voice, Petersen recounts a successful plea to an extended family member for some extra spending money.

While the financial help allowed him to get by at the time, Petersen says he still has a raw understanding of how studying abroad, along with other opportunities at Georgetown, is not an option for many of his peers.

“Not being able to avail yourself of that opportunity is rough,” he says.

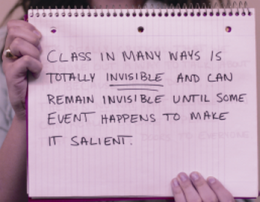

For many students like Petersen, attending Georgetown isn’t a possibility without the promise of financial aid. And even when cushioned by tuition support, the decision to matriculate does not signal an end to the challenges associated with a low-income status. Attending Georgetown brings to light an array of socioeconomic factors for lower and working-class students, forcing many of them to deal with the invisibility of class and the near absence of an active campus dialogue on the subject.

KEEPING UP WITH A ‘HIDDEN CURRICULUM’

Recent studies indicate that at selective universities, issues of class — an identifier that comprises measurements of family education, income, occupation and wealth — are hardly extinct.

According to a 2011 study by University of Michigan researchers, the college completion rate for students from high-income families has grown more than four times faster than the rate for students from low-income families since the 1980s. Another 2011 study, led by Stanford University sociologists, found that the gap in standardized test scores between low-income and affluent students has grown by roughly 40 percent since the 1960s, now surpassing the gulf in achievement between black and white students.

Research shows that the achievement gap in American education is predominantly rooted in students’ socioeconomic status — and when it comes to the top tier of selective universities, the differences can be vast.

According to Leslie Hinkson, a professor in the sociology department teaching a course called Education and Society, a student’s background plays a major role in the assimilation of lower-class students into a campus culture that can value characteristics associated with the well-educated upper-middle class.

“Student background characteristics matter more than anything else, and a lot of that has to do with class,” she says.

Long before a child considers attending college, he or she is exposed to a certain type of vocabulary at home, a certain pedigree of schooling and parental expectations for academic performance. Any one of these factors or others may be linked to parents’ income, according to Hinkson, but ties to higher-income or well-educated social networks helps cultivate a student’s drive to achieve in the classroom, too — regardless of a parent’s income level.

For the students who succeeded in high school without these advantages on their side, the jump to college can become a turbulent experience both inside and outside the classroom.

“In academics, there seems to be what we call ‘the hidden curriculum of schools,’” Hinkson says. “If you don’t have all of that background knowledge that students who went to more selective high schools have … you’re not just learning to think critically here, you’re also playing catch-up at the same time.”

According to a 2003 study by The Century Foundation, 74 percent of students at the top 146 schools in the United States came from the top economic quarter, a measurement of parental income. At those schools, only 3 percent of students came from the bottom quarter and only 10 percent from the bottom half.

Deven Comen (COL ’12), who hails from a public school in a farming town, felt that lack of upper-class exposure when she arrived on campus her freshman year. Although she felt welcomed, some socioeconomic differences were glaring.

Her roommate was a student from an all-girls private school on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and as she struggled to keep pace with her peers from wealthier backgrounds and top-tier high schools,Comen recalls feeling isolated. Comen’s academic transition would become indicative of the uneven playing field in elite higher education.

“My roommate actually proofread my papers. She was my editor for the first two years of college,”Comen says. “And as I caught up with my decent public school education next to some kids who had been at top-of-the-line private schools, there was definitely a slight bit of jealousy.”

Petersen, who received a generous financial aid package upon acceptance, finds that the demands of the classroom, along with close ties with his family, shaped his academic career.

Petersen’s studies must lead to something bigger post-graduation. Landing a consulting or investment banking job that pays about $70,000 would mean a starting salary two-and-a-half times the amount Petersen’s single mother makes at the job she has had much of her adult life.

“You have to understand for people from my situation, you are your family. This is potentially a huge change for your family, especially going to a school of the caliber of Georgetown,” he says.

For students of upper-middle class backgrounds like Ryan Wilson (COL ’12), former co-chair of the Diversity Initiative’s Admissions and Recruitment Working Group, the need to apply a Georgetown education to real-world results isn’t as urgent.

“I’m in the position right now where I’m trying to go to law school, but honestly, if it doesn’t work out, I can go back home and wait until an opportunity comes up,” he says. “And if I were in a lower socioeconomic background, that is not an option, flat-out.”

CLASS ADJUSTMENT OUTSIDE THE CLASSROOM

According to Hinkson, college students’ interactions beyond the classroom are dominated by collective behaviors and norms that sharpen the unseen lines dividing students who are on different points of the socioeconomic spectrum.

“For students from the upper-middle class, it’s just taken-for-granted knowledge and a way of being. It’s what we refer to as cultural capital,” Hinkson says of the social scene, the style of dress and the way of speaking that can signal social class to others.

Just as with academics, students not endowed with upper-crust cultural capital are forced to catch up.

“Schools don’t teach students cultural capital. It’s what you learn at home, and schools reward students for cultural capital,” Hinkson says.

The son of a mechanic and a legal secretary, Ryan Zimmerman (COL ’12) was taken aback when he first set foot on Georgetown’s campus.

“There were people wearing brands I had never seen before,” he says.

These fresh-faced observations would soon have a substantive impact on Zimmerman, a first-generation college student.

“As soon as I got to campus, I started to change how I dressed and how I acted and to step into a role that is very indicative of Georgetown,” he says.

Zimmerman has worked 20 hours or more each week in college to support these changes in lifestyle. With his own drive and the help of others, he has crafted a support network to help manage everything from everyday finances to weekends on the town to future career opportunities.

Jaclyn Wright (COL ’12) says she has intentionally cultivated a social life that doesn’t revolve around spending money as a way of leisure, despite the fact that bars and restaurants in the Georgetown neighborhood encourage these spending habits for many affluent students. A working-class student writing her thesis on access to elite institutions in higher education, Wright says her academic passion stemmed from her social interactions.

For students of higher socioeconomic backgrounds, being cognizant of class difference does not come easily.

“We try to hide behind the broke college student mentality, and we don’t necessarily get into what’s really going on here. We’re all not struggling in the same way,” says Wilson.

Along with other students interviewed, Wilson says he has observed social segmentation based on class — a divide that can only exacerbate the issue.

“I think most people hang out with people of similar backgrounds and are never forced to confront those very awkward moments,” Wilson says, going on to describe interactions he has had while shopping for groceries with friends of lower socioeconomic backgrounds. “There were several times where I’ve been embarrassed where people say, ‘You can’t even tell me how much a gallon of milk costs.’”

Katherine Wolfenden (COL ’12), a former columnist for The Hoya, is working on a senior thesis that pertains to Georgetown’s approach to diversity and difference. Wolfenden says her lower socioeconomic status affects every area of her life.

“Class for me is more a reality of my life, it’s not about what people are wearing,” she says, adding that perceived norms at Georgetown can run counter to many students’ socioeconomic backgrounds. “People here definitely have a warped sense of what normal is.”

EASING TRANSITIONS, ENABLING DISCUSSIONS

Sarah David Heydemann (SFS ’09), a program coordinator in the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor, served as co-facilitator for a discussion on social class in A Different Dialogue this fall. Over the course of many sessions, she found that the idea of assimilation of lower-income students into a higher-class culture was particularly relevant at Georgetown, where the son of migrant-workers may be sitting in class next to the daughter of a major corporation’s CEO.

“I think that that transition can be really confusing, and I don’t know if there are folks out there really talking about [it],” she says.

The Georgetown Scholarship Program, founded in 2004, seeks to ease that shift. The brainchild of Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Charles Deacon and Dean of Student Financial Services PatriciaMcWade, GSP not only opens the door to Georgetown for students from less affluent backgrounds through financial aid but also seeks to keep it open during their time on campus through support and programming.

For Comen, Petersen, Wright and Zimmerman, GSP has been crucial to adjusting successfully to campus life, whether through resume reviews, etiquette trainings, interview practice or support over school breaks, when many low-income students can’t afford to head out of the District.

While programs like GSP and the Community Scholars Program — a Center for Multicultural Equity and Access initiative that provides support to racially, ethnically andsocioeconomically diverse students — help participants of varying backgrounds adjust to Georgetown, students and faculty cite a lack of campus awareness and dialogue on the matter.

“Unless you’ve actually lived it, you can’t understand what it’s actually like to be poor,” Wolfendensays, later adding, “I think it gets to a point where you realize, pity would be so impossible to deal with that you’d rather just not talk about it.”

The feeling of embarrassment or discomfort can go unspoken for many students of affluent backgrounds.

“Do I apologize for the wealth that my parents have? I feel guilty about it a lot of time because I feel like I didn’t do anything to deserve it,” says Anusuya Sivaram (SFS ‘12), an upper-middle class student.

Heydemann sees the discomfort and the gaps in understanding as a communication issue, one that stems from the stigmatization that can accompany conversations about class at all points of the socioeconomic spectrum.

“We as a community really lack the language to talk about class,” she says. “We don’t understand what the word working class, middle class means. I think we need to build the vocabulary.”

For Sivaram, this discomfort can stunt the conversation.

“The fact [is] that there is this difference, and I can’t do anything to solve it without creating more discomfort,” she says.

Becoming more sensitive to the relevance of socioeconomic status — in many cases an invisible piece of students’ Georgetown experience — is essential, according to Heydemann.

“If we don’t make a conscious effort, a sustained effort to pay attention to the little ways that class issues seep into our everyday lives, there’s no way that Georgetown can really become a place that opens its doors to everyone,” she says.

Grounded by his roots but open to different perspectives, Petersen says he has seen cross-class conversation transform his Georgetown experience.

“It’s helpful to all of us to interact across these classes and divisions we have, because it humanizes the stereotypes and the caricatures that are always given to us.”