Ben Perotin (COL ’14) was depressed for four months before he realized something was wrong. “I had an extremely lowered mood, lack of appetite, hopelessness, suicidal ideation [and was] completely withdrawing socially,” he says, speaking with a sort of clinical precision. He taps his fingers on the desk as he enumerates each symptom of the illness that struck in full force during his freshman year.

“There were some times two years ago that I didn’t leave my dorm, other than to maybe eat … for maybe a week at a time. It was completely debilitating,” he said.

And yet, for a long time, Perotin never realized that the feelings that kept him from eating, from engaging with his friends — even from getting out of bed — were signs of depression.

“I was thinking, ‘Maybe I’m just in sort of a funk,’” he said. “I don’t think anyone really realizes when they have something like that. It’s very hard to self-diagnose when you’re actually in the situation to put two and two together and be like, ‘Oh, I am depressed.’”

The realization came when he was at home over winter break. His parents noticed that he was different physically — he had lost 20 pounds — and emotionally. They asked what was wrong, and he told them.

“[My mom] was like, ‘This is more serious. … This is depression, what you’re describing. And we’re going to get you help. This is not something you could or should handle by yourself,’” Perotin said. “And I cried. Because it felt good at some level, because I was like, ‘Okay, they’re supporting me. They’re going to help me. They’re not mad at me.’ … But at the same time, it was just, ‘Oh my god. This is really horrible. This is worse than I thought it was.’”

Isolating as his depression may have been, Perotin is not alone in his experiences. A survey conducted by the American College Health Association in spring 2012 found that almost 11 percent of college students had been diagnosed or treated for depression within the previous 12 months. Nearly half of respondents also reported having felt as if things were “hopeless” during that period, and 86 percent reported feeling overwhelmed by all they had to do.

These numbers are roughly the same as at Georgetown, where about 10 percent of the student body goes to see Counseling and Psychiatric Services each year, according to CAPS Director Phil Meilman. Most students are seeking help for depression and anxiety.

“Throughout the day, I’ll have moments where I just feel overwhelmed with anxiety,” Joe Donovan (COL ’13) said. “Everything tightens up. … I’ll be walking down the street and I’ll just want to curl up in the middle of the street.”

Donovan has dealt with depression since his freshman spring — for nearly three years. He attributes the depression mainly to the academic and extracurricular pressures he felt in college.

“Georgetown has not been a healthy place for me. There are these pressures to succeed that only fit within a very narrow definition of success,” Donovan said. “It’s a way of living that fits some people, but it doesn’t fit me.”

Donovan said he interpreted the exhaustion, disappointment and slipping grades that accompanied his anxiety as signs he needed to work harder. He forced himself to buckle down on schoolwork, but the self-imposed pressure just worsened his depression. By his junior year, Donovan found himself unable to get out of bed some mornings.

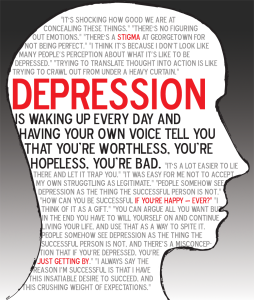

“There’s this disconnect between my thoughts telling me what to do and actually doing it,” he said. “Trying to translate thought into action is like trying to crawl out from under a heavy curtain. It’s a lot easier to lie there and let it trap you.”

Like Perotin, Donovan had trouble identifying his emotions as depression. He felt he had to have a particular tragedy to justify his depression, such as a grave illness or a death in the family.

“It was easy for me not to accept my own struggling as legitimate,” he said. “It took a while before I was able and willing to look at what was going on inside.”

According to Meilman, this struggle is typical of the students that go to CAPS.

“People have different capacities for recognizing emotions. Part of our job is to help students achieve a better self-understanding, recognize issues and engage in problem solving,” he wrote in an email.

Once students realize they are depressed, the prospect of asking for help can be daunting. This can be particularly difficult at a school like Georgetown.

“There’s a stigma at Georgetown for not being perfect … and an exceptional pressure to to keep the facade up,” biology professor Heidi Elmendorf said.

Elmendorf, who herself suffers from depression, teaches a “Foundations of Biology” course that centers on mental health issues. Every student in the class writes a research paper about a particular aspect of mental health, and Elmendorf devotes a full day of class to discussion of her own — and her students’ — experience with mental illness.

Common misconceptions about depression made it difficult initially for Elmendorf to discuss her personal experiences with students, but over time that became a motivation to share her story.

“The fact that I had to think to myself, ‘Woah, would I really tell them this?’ made me think, ‘Well now that’s part of the problem, isn’t it?’” she said. “I became even more committed to sharing it with my students because I thought that that was the exact sort of thing [in which] you need to tip the scales toward openness.”

Lydia Valentin (COL ’16), who took a year-and-a-half-long leave of absence after experiencing a severe depressive episode during her first semester at Georgetown, took Elmendorf’s class in fall 2010 and recalled being shocked by Elemendorf’s discussion of her own illness.

“It was so remarkable because you would never know. She’s there every morning with so much enthusiasm and so much eloquence. It’s just incredible to hear that she’s struggling with this thing that takes such a toll on so many people, that takes such a toll on me,” Valentin said.

According to Elmendorf, many of her students’ reactions are similar to Valentin’s.

“I think it’s because I don’t look like many people’s perception about what it’s like to be depressed,” she said. “People somehow see depression as the thing the successful person is not, and there’s a misconception that if you’re depressed, you’re just getting by.”

For Perotin, the opposite is true. He believes his drive stems largely from his depression.

“I always say the reason I’m successful is that I have this insatiable desire to succeed and this crushing weight of expectations,” he said. “A lot of successful people are very troubled. And it’s not like I want to be depressed to be like them … but I do I really want to relax and just be okay with my life? … How can you be successful if you’re happy — ever?”

Michelle Johnson (COL ’15), a psychology major who went through a period of depression and anxiety during midterm season this semester, said that a lack of dialogue about these illnesses is part of what makes them so isolating and dangerous.

“At Georgetown, people joke all the time about how stressed out they are [or] how little sleep they got, but it’s sort of taboo to talk about your actual stress. It’s taboo to say, ‘This is affecting me seriously,’ and that’s really dangerous,” she said.

When her mother pointed out how much she had changed and persuaded her to ask for help, Johnson turned to professors and her dean — all of whom reassured her and offered their support — but she never sought professional counselling.

“I think I saw CAPS as an extreme that wasn’t necessary for a case like mine, and that might have been a mistake,” she said. “We don’t want to be associated with … ‘psychiatric services.’ We don’t want to admit to ourselves that we’ve gone that far.”

Elmendorf said that this attitude toward CAPS is common.

“Going to see CAPS feels like … a formal declaration that you’re officially struggling,” she said.

Instead, many of Elmendorf’s students come to her asking for advice, just as Johnson sought help from her professors. Elmendorf says her own depression makes her a particularly appealing “sounding board” for students trying to figure out what they are feeling.

“Depression gives me challenges in life, but the silver lining is it has given me empathy and capacity to be there for my students, which I think is the job of adults on this campus. … In that way, I think of it as a gift,” Elmendorf said.

Donovan and Perotin both went to see CAPS, but neither had particularly positive experiences. Both agreed that counselors at CAPS were well-intentioned but ill-equipped to handle the kinds of severe depression they described.

Perotin said that his counselors at CAPS pressured him to take a medical leave of absence during the spring of his freshman year when they saw that his illness required more extensive therapy.

“I can understand from their perspective why the whole medical leave of absence might be an appealing option, but it needs to be handled in a better way, because it makes the student feel like they don’t have a choice,” he said.

Donovan, who first visited CAPS during his junior spring after struggling with depression for almost two years, also said that the counseling was not hugely helpful.

“[The counselor] basically told me ‘I have no idea what is wrong with you.’ And I was looking for direction at that time, so to hear someone say that they didn’t know what was wrong was not a comforting thing,” he said.

CAPS, however, would argue that Donovan and Perotinare anomalies. Meilman declined to comment on Perotinand Donovan’s experiences, but according to a CAPS survey of students who have used their service, 90 percent of students said they benefitted from counseling and half said that the guidance they received helped them academically.

Valentin said that counseling from CAPS has been a critical component of addressing her depression. She regularly met a CAPS counselor before taking her leave of absence in the middle of fall 2010 and resumed therapy with the same counselor upon returning to Georgetown this fall.

“It’s hard to connect with anyone, but he’s been really helpful,” she said. “He listens … but at the same time he helps me discern my behaviors. … He helps me to see the qualities that I never see in myself. He gives me that vicarious strength.”

Nearly every student who suffers from depression must find his own way of cobbling together a coping strategy. Donovan, Perotin and Valentin all take medication that helps them deal with their illnesses. They seek outside support as well — from friends, family and professors but also through hobbies like writing and music.

“I am still struggling with this, but the thought of doing it all without my family, without my support system … I’m incredibly lucky to have that,” Donovan said.

Valentin stressed the importance of unexpected acts of kindness in hedging against her depression. She recalled an afternoon in O’Donovan Hall when a girl she didn’t know smiled at her as she walked by. Valentin was so surprised by the anonymous smile that she started smiling back.

“Smiling at a stranger makes a world of difference,” she said. “We’re all going through something. Maybe that’s the only smile someone will see in their entire day, and people who are suffering so greatly inside can have at least one positive thing happen to them.”

Perotin said he tries to keep his mind occupied in order to prevent negative thoughts from seeping in.

“If I give myself too long without anything to think about … these interior voices always crawl back up and are like, ‘You’re worthless, no one likes you, you have no future, you’re always going to feel depressed,’” he said.

To keep out these thoughts, Perotin listens to music constantly — while walking to class, while waiting for a bus — and immerses himself in schoolwork and mock trial.

“I think that the times that I’m most happy are during finals week,” he said, laughing. “I don’t do vacation well.”

Even so, Perotin said there are days when determination is all that keeps him going.

“Sometimes I can treat [my depression] as an invasive organism … like it’s a bully in my head and I have to actively defend myself. … But emotionally and personally, I’m more afraid it’s just a part of me. And then it’s pure willpower. You can argue all you want, but in the end, you have to will yourself on and continue living your life and use that as a way to spite it.”

Johnson emphasized the need for a broader conversation about mental illness on campus. She said she’s amazed sometimes to find out that some of her friends who never seemed to have a problem are actually struggling with depression.

“It’s shocking how good we are at concealing these things,” she said. “But this is an issue that spans kids our age, and we need to be able to talk about it.”

Donovan agreed.

“Dealing with pressure is something that is, if not universal on this campus, then close to that. But no one talks about it. … Everyone puts on that mask, and then it becomes easy to feel isolated,” he said. “A lot of the conversations about these things tend to happen on a one-to-one basis. … But if the conversation was brought into a group setting, then it becomes a community issue, and that’s how we can start to have an institutional change.”

According to Elmendorf, Georgetown has made efforts to expand discussion about depression on a more institutional level during her 14 years teaching here. Her “Foundations of Biology” course is part of the Engelhard Project, an interdisciplinary program initiated in 2005 to bring discussion of mental wellness issues into Georgetown classrooms. More than 50 faculty members in 25 departments teach Engelhard courses each year, incorporating discussion of mental health into their syllabi in a variety of ways. Elmendorf said that the Engelhard Project has helped launch a broader conversation about mental health on campus.

“I think having brought the discussion into the classroom makes it feel like it’s a part of who we are in an important way,” she said.

Donovan concurred, explaining that openness has been helpful to combating his own depression.

“I do think that dealing with depression has shaped me in a lot of ways. It’s taught me that I need to be honest with myself, that I can define meaning and purpose in my own ways. It’s helped me be a better listener … and led to a lot of really wonderful relationships,” he said. “But at the end of the day, I don’t know what conquering depression will mean, or what that would look like. But I’m confident that I will.”