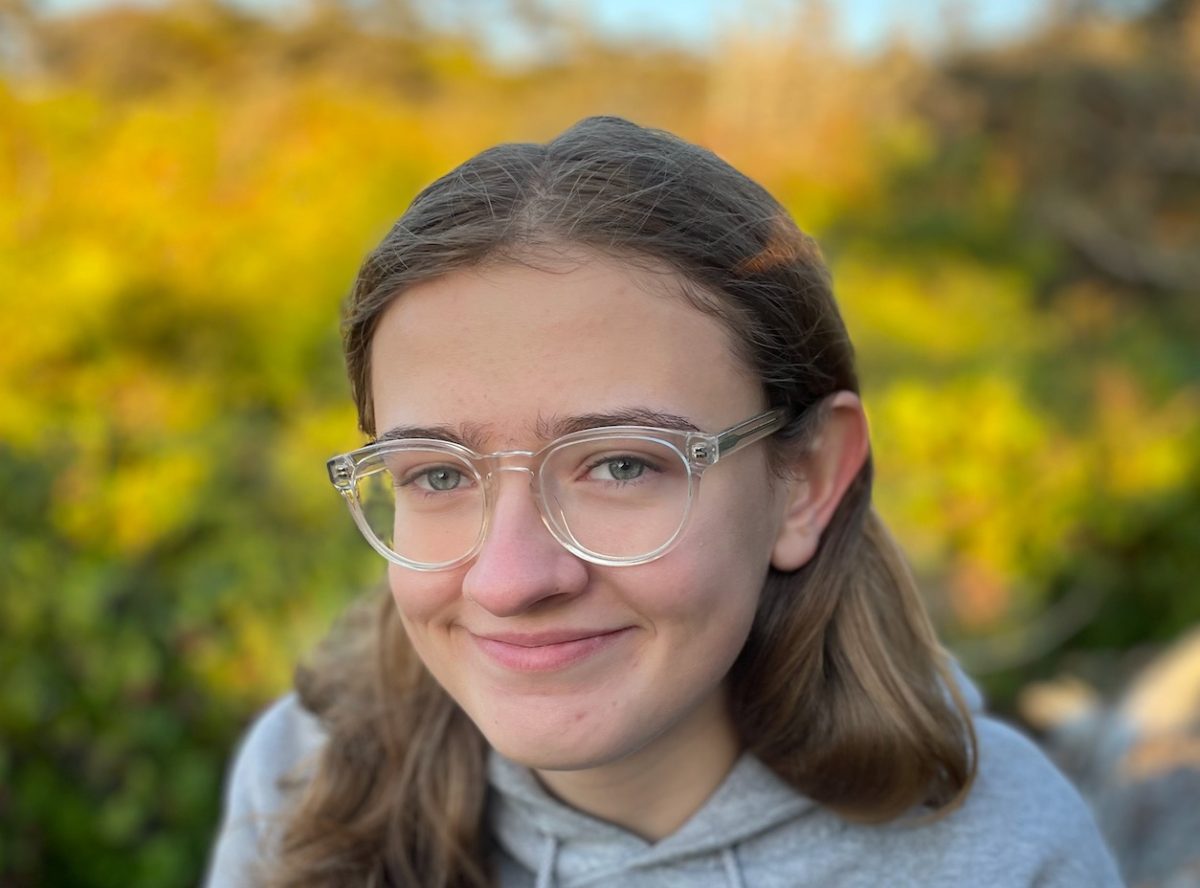

Oxford Centre scholar of Hebrew and Jewish studies Tali Chilson spoke on the poetry and prose of second-generation Jewish writers in London’s East End.

The webinar, titled “Nature as a Respite from Poverty: Parks and Recreation in the Inter-War Novels of Jewish London East End Writers,” took place Feb. 28. The event was a collaboration among multiple institutes on campus, including the Georgetown Humanities Initiative – a project that promotes interdisciplinary activism in the humanities – and the Georgetown Master’s Program in the Engaged and Public Humanities.

Chilson discussed a collection of authors – Simon Blumenfeld, Ashley Smith, Willy Goldman, Charles Poulsen, Bernard Kops and Arnold Wesker – during the lecture who are all sons of working-class, Eastern European Jewish immigrants to England.

Chilson said these Jewish authors played a vital role in England’s literary scene as inhabitants of the East End community of London.

“There is a good case to consider them as the forefathers of a British-Jewish literary revival,” Chilson said at the event. “The East End was city within a city, with boundaries almost as strongly marked as those of some countries as a city of the poor.”

Chilson said over 65,000 of the 150,000 Eastern European Jews who immigrated to Britain resided in the East End.

“Most of the Jews settled in a part of the East End called Stepney, which was populated by Jews who fled antisemitism and pogroms in the Russian Empire,” Chilson said.

As the district’s population density was more than two times that of London, Chilson said overpopulation and unemployment were widespread in Stepney.

“The cramped conditions resulted in tuberculosis, pneumonia, and infant mortality, far higher than the national average,” Chilson said.

In the autobiographical novel “Jew Boy,” written by Blumenfeld, the protagonist relishes opportunities to escape the squalid city and flee into the countryside during summers.

Chilson discussed a passage from the novel and said that it reflects the protagonist’s passion for exploration, which leads him into a journey of self-discovery and identity.

“This story is no longer about a countryside excursion for recreational purposes, but instead is about assimilation, acculturation and belonging,” Chilson said.

Other Jewish authors struggled with the tensions between their Jewish and British identities. Kops’ poem “Diaspora” is emblematic of his inability to truly belong in England without a familial connection to the nation, with one passage highlighting the disparity between the wealth of opportunity for native Britons and the lack of support Kops experienced.

Chilson said Kops’ status as a foreigner gave rise to feelings of dislocation and isolation.

“The beautiful landscape Kops describes is not his,” Chilson said. “His parents were not born in the British Isles and there is no ancestral heritage with the lovely scenery surrounding him. Kops chooses to think of himself as coming from nowhere and going nowhere, creating a modus vivendi of continuous alienation.”

Despite the difficulties of life in the East End, Chilson said it is important to recognize that misery is not the sole emotion expressed in contemporary Jewish literature. In his book “East-Enders,” Smith describes that the East End is full of spiritual values unable to be found anywhere else.

Chilson said that when Ashley Smith returned to the East End for his novel, he found a starkly different environment than that of his childhood.

“What remained was the memory of that vibrant community, with what he called its exuberant social energy,” Chilson said.

Chilson said after World War II, widespread gentrification in London eventually undermined the East End’s Jewish identity.

“After the war, when skyscrapers replaced tenements, and people living in the new flats were unaware of their next-door neighbors, the culture hubs were replaced by bingo halls,” Chilson said. “Most of the Jewish community moved away to the suburbs. The East End, as Smith and the others knew it, had gone forever.”