A high-pitched and emotive violin string invokes the horror of the sale of enslaved people, a spoken-word poem delivered by a deep voice conveys the details of a long journey south. Such is the work of Carlos Simon and Marco Pavé, two faculty members at Georgetown University writing a rap-opera dedicated to telling the story of the 272 enslaved people sold by the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus in 1838.

Georgetown’s campus, steeped in the Jesuit tradition and rife with historically white figures, is not a place many would consider to be home to the genre of hip-hop. Though seemingly opposed to Georgetown’s traditional nature, the genre has recently found a home at the academic institution as a tool for telling stories and uplifting the voices of the oppressed, especially as Georgetown has begun reconciling with its own painful history.

Just a year ago, Georgetown’s student body made strides in addressing its long history with slavery when it voted to pass the GU272 referendum that would establish a semesterly fee to go toward a fund to benefit descendants of the 272. The historic initiative offered hope for what a progressive academic institution could look like; before the school failed to enact the fee, it was on its way to position itself as a vanguard of institutional justice.

While the administration has not followed through on the GU272 referendum, Georgetown has maintained its commitment to activism in other ways. From the establishment of the school’s first-ever artist in residence, to hip-hop dance groups on campus paying homage to the genre’s Black roots, to a rap-opera fusion piece dedicated to memorializing the histories of the descendants of the 272, Georgetown has become a place of convergence for activism and hip-hop.

Elevating Voices

During the fall of 2019, Memphis-based rapper Marco Pavé, born Tauheed Rahim II, was instated as Georgetown’s first artist in residence.

Growing up, Rahim knew he was into music, but he never pictured himself living out his dream of being an artist living on Georgetown’s campus.

“I pretty much started rapping when I was eight years old,” Rahim said in an interview with The Hoya. “It’s everywhere in my upbringing; music was always a big part of my life growing up. And as I grew older, I started to see people that looked like me taking control of their lives with this platform.”

It wasn’t until Rahim got somewhat older that he started to pivot from an interest in just making music to an interest in its ability to effect change, and that Georgetown seemed like a viable place to make that change.

“In 2013 was when I made a change and really started to think about what people might call social justice,” Rahim told The Hoya. “I hosted a benefit concert for the literacy rate in Memphis that raised over $20,000, and that really catapulted a lot of things. And then I had ideas of residency and ideas of more formally supporting artists that they can really have the opportunity to do what they’re trying to do.”

When reflecting on the work he does for Georgetown, Rahim emphasized the fact that it was not just Georgetown he was catering to, especially considering that other areas throughout Washington, D.C., have a rich history of hip-hop themselves.

“The work consists mostly of organizing and curating events that I think would be beneficial and useful to the Georgetown community, but also to the D.C. community in general,” he said.

The residency, in collaboration with the African American studies department and the department of performing arts, offers Rahim the opportunity to meaningfully engage with the Georgetown community, exposing them to the richness of hip-hop and starting larger conversations about race, culture, industry politics, fashion and more.

“There was an introduction event where I introduced myself to the community, performed and had professor Charles Hughes, a music writer, come and interview me. The second event was the sneaker culture event. And that was super, super impactful. We probably had, like, 200 people show up.”

Similarly, in the fall of 2019, Georgetown welcomed award-winning classical composer and musician Simon to the performing arts department as a new professor.

Though some people assume only certain genres lend themselves to a politically charged message, Simon would disagree. Although his primary genre is classical, his presence within the genre is as disruptive as any rapper’s.

“I’m hesitant to use the word classical because it has so many loaded connotations, just like all the other genres have assumptions built in,” Simon said in an interview with The Hoya. “The classical space is traditionally elitist. You think, ‘Oh, here is the symphony orchestra, you’re not going to see Black and brown people.’”

Though Simon operates within a traditionally white genre, he does not feel restricted in terms of conveying the messages he wants to impart. For him, music is a means to an end, not the end itself.

“There are pieces that exist that talk about Black Lives Matter in police brutality and there are pieces that talk about their historical side of things like the great migration,” Simon said. “And these are all things that are related to social justice and social issues in our country. But using the music is just a tool for me; it’s not the end-all be-all. That’s why I’m hesitant on using genre.”

In the same way that someone like Rahim, operating in a predominantly white space at Georgetown, must focus on issues of diversity, in a genre as typically white as classical music, Simon feels as if it’s his responsibility to elevate voices who aren’t as frequently afforded access to those spaces.

“As I go into the classical space as a composer, I think it’s incumbent on me to kind of really talk about the issues of inclusion and that space and diversity,” Simon said.

Requiem for the Marginalized

Both Rahim and Simon have recently embarked on a collaborative project that aims to situate itself within the history of the 272 descendants from the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus’ sale of enslaved people, archiving the descendants’ memory and telling their stories through an artistic medium.

“It’s really about stories for me and being able to tell a story, so that someone else can find sympathy, or empathy, being able to kind of connect with that person in their plight. And for me, as a Black man, I want to tell the stories that are true to me and my background,” Simon said.

Simon takes particular issue with the hypocrisy of a bastion of liberal education having participated in something as violent and degrading as slavery.

“It was mind-boggling to me, as a Black man, that you have this prominent university in America participating in slavery, actively spending, selling slaves, owning slaves,” Simon said. “We always associate these things with the South, not the North. The North was always associated with ideas of freedom and abolitionists and all these other things, but here, you have this university in D.C. participating in slavery.”

In an effort to illuminate the systemic issues plaguing both Georgetown and the United States as a whole, Simon and Rahim started work on a rap-opera, commissioned by Georgetown, entitled “Requiem for the Enslaved.” The title of the work alone signals a need for remembrance, for the acknowledgment of the pain that was endured.

“My platform has always been music. So the opera only made sense as a sort of twofold project to really honor the lives and legacy of the enslaved and the role that they truly had, not just with Georgetown, but the American society as a whole, as well as to the highlight the the role of slavery and and the systemic impact that it has had on our society,” Simon said.

Simon’s piece is slated to release virtually in May 2021 and blends the requiem form with spoken word as Rahim provides narrative rap.

“I’m using hip-hop, with Marco Pavé as a storyteller, and then I’m using a lot of classical elements for musical interludes like a small chamber group, violin, cello, flute and clarinet,” Simon said.

Ultimately, the beauty of a piece like “Requiem for the Enslaved” comes from its ability to center the stories of those who are marginalized, according to Simon.

“When I’m working with Marco Pavé, who’s a hip-hop artist, it’s like we’re bridging these two worlds of classical space in the hip-hop world. We have to come together, and by doing so we are including voices that have been traditionally marginalized and underrepresented and including stories that have not been included in the narrative,” Simon said.

Reflecting Within

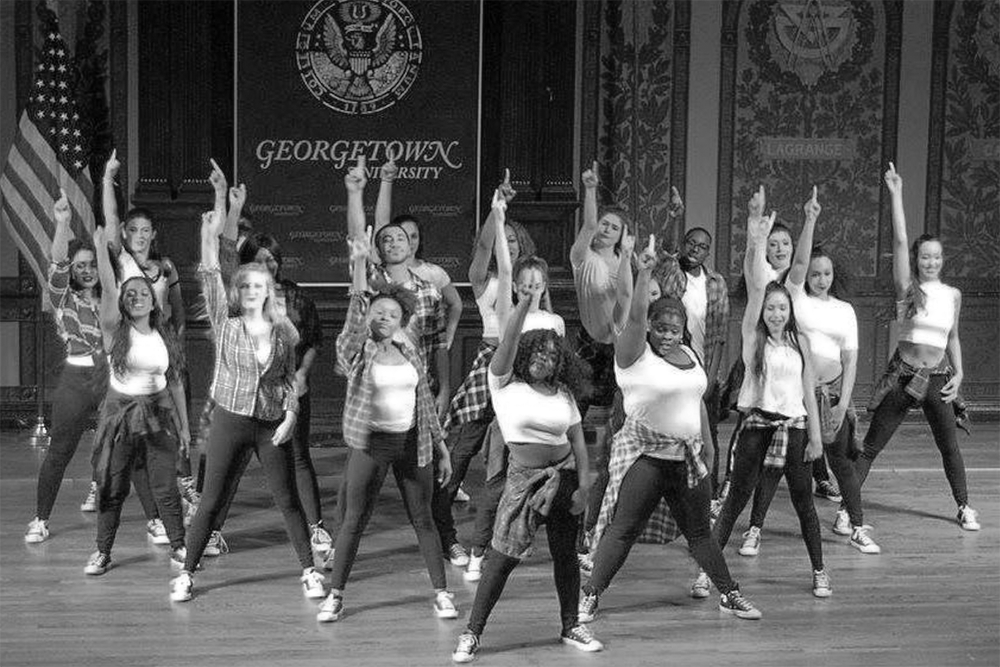

The student body has also used the convergence of hip-hop and social justice on campus to create something powerful in other spaces. Groove Theory, the hip-hop dance group on campus, has for several years performed semesterly showcases and has also partnered with charitable organizations like Best Buddies, an organization focused on building friendships between people with and without intellectual and developmental disabilities founded at Georgetown.

Only recently, however — particularly in the wake of the police murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others and the resulting Black Lives Matter protests this summer — Groove Theory began to pay closer attention to hip-hop’s roots in protest and expression by the Black community, according to Groove Theory’s Social Media Chair Philan Morgan (COL ’22).

“Regardless of where a person begins their journey with hip-hop music or dance, its history is undeniably based in the community and based in activism,” Morgan wrote in an email to The Hoya. “This year, we’ve decided to take a step back and critically examine our role as a ‘hip-hop dance team’ not only on campus but also within a larger context.”

After a member of Groove Theory attended a town hall on D.C.-Maryland-Virginia hip-hop culture, the club was inspired to give more consciousness to hip-hop’s long history of amplifying voices in the Black community crying out for social change, according to Morgan.

“It helped us come to the conclusion that in a way we are divorced from hip-hop’s foundational history and the Black community that it originated from,” Morgan wrote.

Club leadership decided to host weekly “Dance Discussions” unpacking the important history and culture of hip-hop and other Black music and dance styles, including breakdancing, disco, house and voguing. Discussions center around the creation of these dance styles as forms of activism for marginalized groups in the United States.

“We have found that these discussions influence our current understandings of our own activism and how we wish to interact with different communities and movements, such as Black Lives Matter,” Morgan wrote. “To quote one of our members, Alexus Wells, ‘hip-hop is a lifestyle embedded in justice.’ If we are to participate in this lifestyle, then justice must be part of our mission.”

Consciously embracing political commentary in its choreography to come in future in-person rehearsals is one avenue by which Groove Theory hopes to tap into hip-hop’s roots as a form of protest by oppressed communities, according to Morgan.

“We’re all pretty politically-minded people and I think that’s something that we bring with us into the studio. I think that there is a general misconception that hip-hop can’t be too political or that it needs to be separate from the political. But hip-hop is inherently political; it’s derived from and popularized by historically marginalized voices,” Morgan wrote.

As Georgetown continues to reckon with its past and with how it engages with the Black community and Black culture today, hip-hop proves to be a suitable vehicle for reflection and change.

“That’s how I view Georgetown,” Rahim said. “It’s really like a blank canvas of being able to show people that this is what the world of hip-hop looks like. This is what hip-hop can do.”