William Gaston, after whom the historic Gaston Hall in Healy Hall is named, owned 163 enslaved people and supported judicial opinions that opposed equal citizenship for Black people, according to newly released research obtained by The Hoya that was conducted by a Georgetown University Law Center (GULC) professor.

Previous accounts of Gaston’s slaveholding painted an unduly progressive picture of his legal stances on slavery, stating he only owned up to 40 enslaved people, according to a letter sent to University President John J. DeGioia (CAS ’79, GRD ’95) by John Mikhail, a Carroll Professor of Jurisprudence at GULC. Gaston was Georgetown’s first student and also helped secure the university’s federal charter.

Mikhail found an estate inventory that listed the names and ages of 163 enslaved individuals, including 21 children under five years of age, whom Gaston owned at the time of his death, when researching on Ancestry.com, where he had gone to find tax and census records on Gaston. Mikhail’s research also suggests Gaston may have enslaved up to 26 families spanning three or more generations.

In the letter, Mikhail said uncovering the truth about Gaston’s ties to slaveholding is an important step in raising awareness about the enslaved individuals connected to Georgetown’s legacy and their families.

“Of course, these children and their siblings, parents, and grandparents were not numbers. Each one had a name, a story, and people who loved them,” Mikhail wrote in the letter. “In all likelihood, many of them had descendants, some of whom are alive today.”

Mikhail’s archival research also reveals that while Gaston was a judge on the Supreme Court of North Carolina, he ruled that Black people, including former enslaved people, were state citizens in North Carolina v. Manuel. However, he upheld a state law that favored racial discrimination and white supremacy, rejecting the concept of equal citizenship under the law for Black people. Later in North Carolina v. Will, Gaston ruled that an enslaved person’s use of self-defensive force against their overseer was almost always unlawful.

Upon uncovering this information, Mikhail said he felt it was important to share that Gaston was a much more significant slaveholder than had previously been understood.

“I started to realize that there was more and different information here than people were aware of,” Mikhail told The Hoya. “It motivated me to get as accurate a picture as I could and then share it with people because I thought it might raise awareness and change the conversation around Gaston.”

In collaboration with other faculty members and students, Mikhail has spent the past six years researching Gaston. Beyond Gaston’s connections to political and legal history in the United States, Mikhail said he was inspired to learn more about Gaston following the publication of the 2016 report by the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation.

Mikhail said his research produced two main findings that contradicted previous understandings of Gaston.

“First, Gaston’s slaveholding was far more extensive than the Report implies,” Mikhail wrote in the letter. “Second, his judicial opinions involving race and slavery were less progressive than is often assumed.”

DeGioia founded the Working Group on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation in 2015 following dialogue surrounding the designation of Mulledy Hall, which was named for Georgetown President Thomas Mulledy. Mulledy authorized the sale of 314 slaves owned by the Society of Jesus in Maryland in 1838, referred to as the GU272+, to financially sustain the university.

In 2016, the Working Group published a report reflecting on its findings with recommendations for DeGioia, one of which called for further research on campus sites and programs named for people with a connection to the history of slavery. The group disbanded after publishing the report, according to professor Adam Rothman, curator of the Georgetown Slavery Archive and a former member of the Working Group.

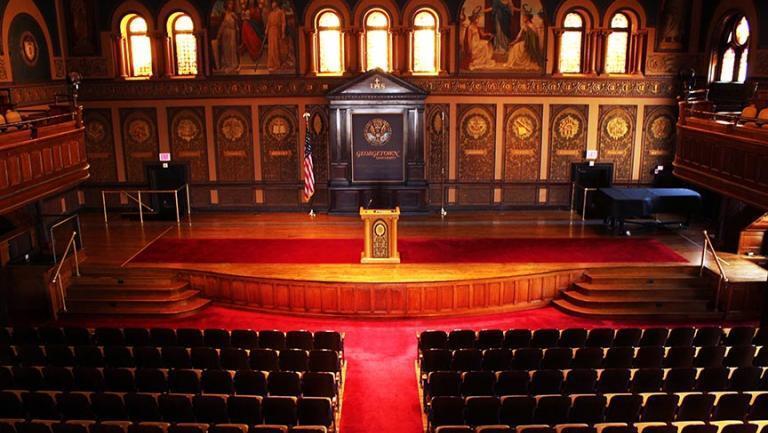

The group was led by History Professor Fr. David Collins, S.J., and consolidated the work of faculty, staff, students and graduates to provide advice and recommendations on how to properly acknowledge and recognize the university’s historic ties to slavery. Gaston Hall, a celebrated auditorium located in Healy Hall that hosts many of the heads of state and public figures who visit campus, was on the list of campus locations connected to slavery.

Mikhail said he shared the letter with every faculty member on the Working Group and is in the process of disseminating it to the larger campus community to raise awareness about Gaston’s extensive slaveholding.

A university spokesperson said the university has been in contact with Mikhail since DeGioia received his letter.

“President DeGioia has met with Professor Mikhail to hear about his findings directly. The University is closely reviewing his letter and considering how we may proceed given the emergence of this new research,” the spokesperson wrote to The Hoya.

Rothman said he helped Mikhail transcribe Gaston’s estate records and said his research answers the Working Group’s call to action.

“This is what is supposed to happen — faculty and students and anybody else who else is interested takes up the time and runs with it, and continues and extends the research that we were part of,” Rothman told The Hoya.

Richard Cellini (COL ’84, LAW ’88), secretary-treasurer of the Georgetown Memory Project, an independent group that aims to identify enslaved people sold by the university in 1838, as well as locate their descendants and honor their legacy, said the contents of the letter represent a larger trend of information around the history of slavery going uncovered.

“I really was shocked that that Gaston’s involvement with slavery was so extensive and so hidden to the rest of us,” Cellini said in an interview with The Hoya. “But I was not surprised because we keep discovering time after time after time, not just at Georgetown, but all across the country, how much of this history has been erased and displaced.”

Professor Maurice Jackson (GRD ’95, GRD ’01), a Working Group member, said Mikhail’s research is part of a continual process of discovery, correction and revision that is characteristic of historical research.

“We didn’t have these details, and things just keep coming out,” Jackson told The Hoya. “This is just part of an ongoing process and he’s made a worthy contribution.”

Cellini said the findings prove the need for ongoing research in conjunction with the university to further investigate the links between Georgetown and its history of slavery.

“There should be new working groups, and they should be much broader than the old one,” Cellini said. “There’s a lot of stuff at Georgetown that still have very close ties to slavery.”

Rothman said Mikhail’s research illuminates the selectivity of memories about Gaston, which is highlighted by the distinction and prominence of Gaston Hall.

“It is a place that is suffused with historical memory except for the memory of slavery and Gaston’s relationship to it,” Rothman said. “Revealing this history just accentuates how heavily curated our historical memory is and how much it overlooks. This is all part of the process of telling the truth about our past.”

Hoya Alum • Oct 3, 2022 at 10:19 pm

I am always surprised at news of major discoveries. Ancient dinosaur bones and the like I can understand; layers of civilization have covered them for ages, and we just haven’t been around long enough to find them all yet.

But another discovery of this kind at Georgetown rattles me down deep — is a much-needed wake up call for us all to heed as we uncover our own familial, institutional, and national histories. and as reckless calls are made around the country for dangerously narrowing the curricula of our children’s schools.

The closing quote by Rothman captures the layers of complexity and nuance involved in such findings and, more importantly, the need to continually rethink and radically expand the ways we curate our knowledge of our past — our collective memory. Yet, our collective memory is only as valid as its genuine willingness and insistence to include all people’s histories.

I am cautiously hopeful as I wait to see how the university leadership and greater community respond to this revelation. Hopeful that they solicit many diverse voices in thoughtful dialogue and deliberations, and hopeful that their follow-through will be more transparent and expedient than the commitments made thus far in addressing the history of slavery at Georgetown.